The Midwest has a meth problem – and it’s not going away

Words by Sarah LeBlanc

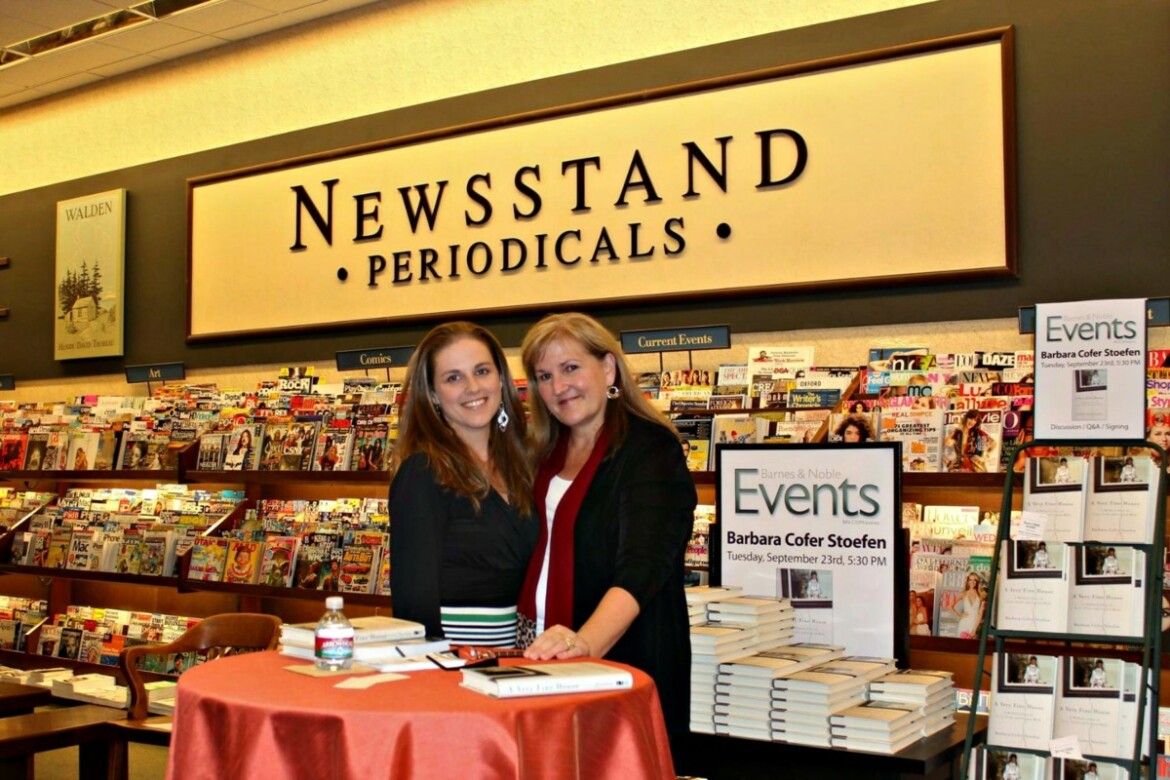

Photos by Barbara Stoefen

- Annie stands atop Mt. Bachelor in Bend, Oregon.

- An 8-year-old Annie with her mother.

- With her mother, Annie proudly stands six years sober at her graduation.

- Annie poses in her senior portrait.

- Annie attends the 2015 UNITE to Face Addiction rally in Washington, D.C.

- During her honeymoon in Paris, Annie lights a candle at Notre Dame, “for all those who still suffer.”

She started with a drink.

By the time she was 19, Annie Stoefen was an alcoholic. Her mother, Barbara Stoefen, said that drink was the start of a downward spiral that eventually led to her daughter’s meth addiction.

“My daughter — she was the pretty, brilliant, shy, timid teenager, and to look at her, you would think this girl could be Miss America,” Stoefen said. “The beautiful girl next door. She could be anything she wanted. But she was never comfortable in her own skin.”

Stoefen describes addiction as a disease that feeds off co-occurring disorders. For Annie, these were anxiety and depression, and while her parents sought treatment for her, something inside of her felt like it didn’t fit.

Battling Addiction

When Annie was at the University of Oregon, she partied. At one of these parties, she was offered a white substance. Having snorted cocaine a couple times, she accepted. But this wasn’t cocaine — it was meth.

“It took over her life pretty quickly,” Stoefen said. “It was like having her die, but she was still alive.”

Almost immediately, Annie became addicted to meth. After telling her mother she was using, Stoefen said she and her husband freaked out.

“At first, the natural parent response is to try and fix it and to protect them, and you soon learn that’s what really allows an addict to keep using,” Stoefen said. “We did everything we could to educate ourselves as quickly as we could and did the very hard and painful work of allowing her to experience her own consequences.”

The Stoefens did try treatment twice, but with little success. Eventually, Stoefen said, Annie simply had enough consequences.

“She broke into our house and stole from us, so we allowed her to be arrested,” Stoefen said. “I testified before the grand jury.”

For Annie, that was the push she needed. She’s in recovery, but there is no cure for meth addiction.

Meth in the Midwest

When someone becomes addicted to meth, the effects of the drug can take a visible toll. Teeth begin to rot, skin becomes paler and a person can fluctuate between being hyperactive and then crashing for days. Meth provides a high for the user that quickly becomes addictive.

“Meth is one of those drugs that takes over your whole life,” said Dave Boysen. “You’re only worried about getting more meth and getting high, you’re not worried about cleaning the house and making sure your kids have food in the fridge— you’re just worried about getting meth.”

With rural towns and open spaces, the Midwest has become a hotbed for meth labs. Counties in Missouri and Michigan have some of the highest concentrations of meth labs in the country, and while those numbers might be going down, use isn’t.

Boysen has been the captain of Kalamazoo Public Safety for five years. He leads the Kalamazoo Valley Enforcement Team drug unit, which includes 20 officers focused on tackling drug use in the county. In 2016, his team busted 45 meth labs, and since 2004, there have been 1,120 meth seizures in the county. He’s participated in hundreds of searches on properties that were found to house a meth lab.

Kalamazoo County, Michigan, is just one county in the Midwest where the number of meth labs reaches over 300. Kalamazoo, with a population of just over 75,000 people, is the county’s largest city — but it’s still small enough that people have been able to cook meth without the odor attracting too much attention.

That odor is part of what makes cooking meth so risky, and why smaller, more rural areas typically have a higher concentration of meth labs than urban areas. The smell of ammonia is a key hint that a house holds a meth lab, and that can lead to neighbors or passersby reporting the smell to the police. The smell of ammonia and the flammability of the materials needed to cook the drug has caused some meth cooks to abandon the project in favor of cheaper (and less explosive) options.

“What’s happening now is we are getting flooded with meth from Mexico, and they call it ice, and so what we’re seeing is a ton of those types of cases but a lot less labs because the Mexican ice is so much cheaper,” Boysen said.

Mexican ice is a purer, less expensive form of meth that can be bought on the streets of almost any town in America. Boysen said the rise in Mexican ice was driven by a lack of demand for Mexican marijuana after several states legalized the drug, forcing dealers to go with the market and turn to heroin and meth. The availability and affordability of Mexican ice has made it an attractive alternative to cooking meth.

“That’s why lab numbers are down across the country,” Boysen said. “It’s got nothing to do with use, because use rates are as high as ever, but it’s the ice coming in. Just last year alone, my drug team seized 16 pounds of ice.”

It’s become more difficult to the cook the substance in the last five years. In Jefferson County, Missouri, Lieutenant Colonel Tim Whitney was part of a team that successfully approached cities about passing laws requiring a prescription for pseudoephedrine.

“There’s a couple different manufacturing processes that can be used, but the one common denominator is you have to have that pseudoephedrine,” Whitney said. “So if we can prevent that pseudoephedrine from getting into the wrong people’s hands, then we can prevent the labs.”

Whitney led the county’s drug task force in 2012, when they busted 350 labs — the highest number that had ever been found in the United States. He says that while this number is substantially higher than other counties, his 10-member task force was specifically focused on finding meth labs.

“We’ve been called Metherson County and the meth capital of the world and all those things because of our high meth lab seizures,” Whitney said. “I would argue that we’ve never had a problem larger than anyplace else — certainly we are rooted in that, but we were very aggressive in our enforcement actions.”

But even with a task force, it’s difficult to find and bust every single meth lab in the county, and unfortunately, preventing meth labs is not always as easy as just passing a law. There are a couple of drawbacks to legislation. Families that live in counties that have passed the law now have to get their doctor to call in prescriptions to pharmacies. In Michigan, the purchase of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine-containing medicines are tracked and limited, so they can’t be bought in bulk. But meth cooks have found other methods of acquiring the drug.

“They just go to the homeless shelter, pick up a vanload of homeless people and drive them around to the pharmacies and buy psuedo pills, and they buy them for up to $50 a box,” Boysen said. “I don’t think meth labs are going down because the ingredients are harder to get, I think it’s just they don’t need to cook it right now because of all the meth available on the street to buy.”

This high-risk, high-reward tactic of having others buy drugs for cooks or dealers at a marked up price is called smurfing, and it’s an unintended consequence in states where pseudoephedrine laws have been passed.

With so much meth on the streets, and cooks getting more creative in where and how they produce their product, law enforcement has been forced to prioritize cases that pose the most danger to the public.

“You’re not going to arrest your way out of a problem,” Boysen said. “Our job is to target those people that are making it or bringing it into the community — that’s who we go after as a drug team.”

Boysen has witnessed apartment buildings burn down because of a meth explosion, costing millions of dollars in damages and leaving many homeless. Meth breeds crime in communities, with people stealing to support their habit and putting the lives of their families and neighbors in danger.

“If we get a tip of someone cooking in a residential house, especially if there’s kids living there, we prioritize those,” Boysen said. “But once the warmer months hit, people will be going outside and cooking in the woods and things like that — you know, that’s just tough.”

Cooking meth is a toxic process. It releases chemicals into the air that can cause illnesses and pose a danger to those nearby. In a residential area, these dangers are elevated. Whitney estimates that of the 700 children in the foster care system in Jefferson County, a majority have been displaced by an unsafe environment caused by a parent or guardian addicted to drugs.

“It impacts families — the parents are dealing with an addiction and that addiction is so strong, whether it’s heroin or meth, that it really drives their lives and drives the decisions they make,” Whitney said. “The kids aren’t being cared for properly so a lot of the time those children end up in foster care through law enforcement and by family services.”

Meth users and cookers can’t be stereotyped into one demographic. Addiction doesn’t discriminate, and people of any socioeconomic status can become shackled by disease.

Criminalizing Addiction

Dr. Barry Goetz is an associate professor of sociology at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. While he notes that people can be found to use drugs at around the same level across race, ethnic and socioeconomic lines, that’s not the case for those prosecuted under the criminal justice system. And putting someone in jail isn’t the cure for addiction.

“Just sort of think about the logic of that — you’re putting someone in jail for their dependency,” Goetz said. “You’re putting someone in prison for using some sort of intoxicating substance, and on some level that doesn’t make sense.”

Instead, Goetz sees drug courts as a step in the right direction. The Michigan courts system defines them as supervised treatment programs for nonviolent offenders who have struggled with substance abuse or alcohol dependency, and there are 84 in the state. Goetz said these are a better solution than jail, but they’re not perfect.

“They still require that you be criminalized first,” Goetz says. “That is, you have to go through the system of being charged with a crime, and then either you go into the drug court as a matter of probation or as a matter of sentencing, like a sentencing alternative. You still have a record, but any treatment is better than prison.”

If a person is able to combat meth addiction and enter into recovery, they’re still faced with obstacles that will affect them throughout their life. Addicts may go into remission, but are not fully recovered. If treatment is successful, they need stabilizing factors to prevent them from backsliding.

“A lot of people who are addicted have to have other things in their lives be stabilized first — their jobs, their educational situation, their family life,” Goetz said. “I think that’s one of the important things the drug court movement did.”

While Stoefen agrees that the criminal justice system is institutionally flawed, she wants treatment to be more in the hands of medical professionals. She became the president of Oregon’s Meth Action Coalition after Annie recovered and she advocated for education on prevention and, with her daughter, participated in awareness programs in schools.

“Somehow, the disease of addiction became the responsibility of the legal judicial system rather than the medical community,” Stoefen said. “It’s in everybody’s best interest if it’s a disease that’s treated and the answer is not to round up everybody and throw them in prison.”

Life After Addiction

Meth affects every state in the country, and while some areas might have higher concentrations of meth labs that act as indicators of use, the Midwest is not alone in its struggle against widespread use. Recovery is a lifelong process and a mark of strength for those who are able to win internal battles every day.

Annie has been sober for more than 10 years. Her mother boasts that she is now a grandmother, and has her daughter back. Hers is a story not often told by those who have struggled with meth addiction.

The United States has a drug problem. In the past year, over one million people have used meth, and for many, it isn’t one-time use. Law enforcement works to reduce the danger from meth labs, but many departments are spread thin. Prisons attempt to keep dangerous people from society, but end up creating a revolving door of abusers who can’t reach recovery.

The number of meth labs in certain counties of the Midwest have earned the region a reputation. Michigan and Missouri have taken steps to combat rampant meth use, and while they have been effective, the solutions aren’t foolproof. Meth continues to riddle the country, but it’s the stories of people like Annie that give hope for recovery.