Only half the U.S. believes global warming is caused by humans. How do climate scientists cope

Words by Angela Ufheil

Pennsylvania rock formations fascinated Melissa Berke when she was a kid. She grew up in Ohio but had family in New York, and visits required a road trip through the Quaker state. “You drive on all these really cool roads where you see all this carved rock,” Berke said. “So I really wanted to understand how that got there and why.”

Berke never stopped wanting to understand the world. Not in a vague, existential way. She wanted to study the physical earth beneath her feet and learn what sediment layers could tell humans about ancient earth history. So she got a Ph.D. and became a researcher and assistant professor in the University of Notre Dame’s Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Earth Sciences in Indiana. She’s passionate about her work and happy to patiently explain it to people when they ask. The only problem?

She’s one of those dreaded climate scientists.

Multiple surveys show that about 97 percent of actively published climate scientists agree that humans are causing the global climate to warm. But a lot of people don’t believe them.

Only 48 percent of Americans believe that the Earth is warming due to human activity, according to a 2016 PEW Research study. Fewer believe climate scientists have reached a consensus on global warming: just 27 percent.

It seems that a sizeable portion of Americans don’t think highly of climate scientists. A mere 32 percent say that “the best available evidence” influences climate scientists. More people — 36 percent — think they’re influenced by desires to advance their careers.

And, of course, President Donald Trump has not exactly sung praises to climate scientists. He once tweeted that “the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive,” and has called climate scientists “hoaxsters.” He has since said it was a joke, but continues to say that climate scientists are misleading the public, and his recent budget proposal makes big cuts to EPA and NASA programs devoted to studying climate change.

When asked if all this vitriol and doubt cause her moments of despair, Berke said “Yeah, like, most minutes of most days.” But then she laughed. “If you let yourself get bowled over by it, it’s pretty easy to do, right? You kind of have to soldier on.”

Soldiering on, though, can be tough — especially when the public seems to think the science is confusing at best and bogus at worst. But Berke, along with other climate scientists, won’t give in to despair without a fight.

Misunderstood

Berke’s job sounds a little like magic. She hops on a boat and sticks a long tube down through the water and into the bottom of the lake or sea. Once she retrieves a sample of the mud layers, she’s able to learn pieces of information about the past, like how warm the water was thousands or millions of years ago.

It’s easy to see why some people are skeptical. For someone without a scientific background, learning about water’s temperature from mud sounds crazy. Forget about figuring out the temperature from thousands of years in the past.

Even if someone wanted to learn more about the process, it can be daunting. Most people don’t know a climate scientist they can talk to, and even if they do know one, they might be afraid to ask.

The divide between climate scientists and the rest of the world makes a great breeding ground for conspiracy theories.

“I definitely have heard people say that they think climate change is a hoax,” Berke said. “I definitely have extended family members who don’t quote-unquote believe in climate science, believe in climate change. I mean, I’m related to them. Why would they think I would lie to them?”

The JOIDES Resolution, the International Ocean Discovery Program ship Melissa Berke boarded in Mauritius to take samples from the Indian Ocean near southeastern Africa. Berke is quick to point out that the boats for research aren’t always so big — she’s taken samples from aboard a rowboat. Credit: Melissa Berke

If her family asked her about her work, Berke would start by explaining sediment layers. When organic material like plant stems and leaves, as well as rock particles, get into a body of water, they sink to the bottom and settle. Then, more particles settle on top of them. Eventually, after thousands of years, those particles are buried deep within the lake’s floor. The deeper the particles, the older they are.

There are several ways to figure out what went on in the past once the mud’s been removed. One way is looking for chemical fossils, the “underdog of the fossil world,” according to Berke. She uses a leaf as an example. Leaves have a waxy coating on them that protects them from the sun. Even after the leaf decomposes, the chemicals that made up that waxy coating remain. If the leaf ended up in the lake, then those chemical particles sink to the bottom and are enveloped in the sediment layer.

The little wax-layer particles that could are preserved beneath the mud for thousands and thousands of years. Until Berke comes along, of course. Her long, straw-like sampling tube reaches deep into the mud and extracts those preserved particles. The harvested samples make the long journey back to her lab. “We do a series of separations in the lab based on chemical polarity,” Berke said. “We’re able to separate out different compound types, different molecules, and it’s that separation that then allows us to identify the different groups of organisms or processes that used to occur.”

Berke and her group figure out the types of organisms and processes by comparing the samples to modern-day chemical remains. If the old sample and the modern sample have similar chemical makeups, they’re able to figure out what the sample actually was. Then they can track the chemical changes in that type of substance over time, and learn about what changed through the years.

“Mud samples, or “cores,” after they’ve been extracted, cut into smaller sizes, and halved. Chemical fossils found in these cores can inform scientists about climate conditions from thousands of years ago.” Credit: Tim Fulton

Berke’s method of reconstructing the past environment is just a small part of the climate scientist puzzle. “We do these reconstructions in lots of different places with lots of different techniques,” she said. “When they confirm each other, we feel pretty confident.”

Climate scientists perform numerous experiments to double check each other’s conclusions. “The whole key to science is trying to replicate results,” Berke said. “And so, it’s not just one study or one measurement that shows an increase in temperatures. It’s thousands of records from many different places.”

That need to check one another’s results can look, to an unscientific eye, like climate scientists are doubting one another. Christie Manning, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota with a Ph.D. in cognitive and biological psychology, said that science is, by its nature, a critical pursuit.

“Part of being a good scientist is to not just accept evidence without questioning where that evidence came from, how it was collected, whether sound methods were used, whether the questions that were asked were appropriate and whether the analysis that was done was rigorous,” Manning said. “But that can make it look like there’s lots of disagreement.”

Berke has noticed that the way scientists communicate with one another is confusing to the public. “We don’t say ‘100 percent absolute, never going to change,’” she said. “And that makes it sound like scientists are doubtful when that’s not at all what’s happening, that’s just the way scientists talk.”

But the way scientists talk seems to be hurting their cause. “If you are trained as a really good scientist, you are trained to communicate scientific results well,” Manning said. “You may not be trained to communicate with the public. A lot of the scientific concern is getting lost in translation.”

When something important is at stake, people tend to adapt. That’s how climate scientists feel about the planet, and they’re taking action to improve their messaging. The Center for Research on Environmental Decisions, for example, provides videos, books and other resources to improve communication.

Climate scientists are also trying to establish that they’re more than scientists studying global warming — they’re people, too. Berke said she wants to end the “Big Bang Theory thing.” “I think there’s a stereotype of scientists just working nonstop,” she said. “But most all the climate scientists I know, myself included, go home. We sleep in our beds. We have husbands, wives, kids, pets. We do things for fun. I’m doing this whole interview with a cat on my lap. How about that?”

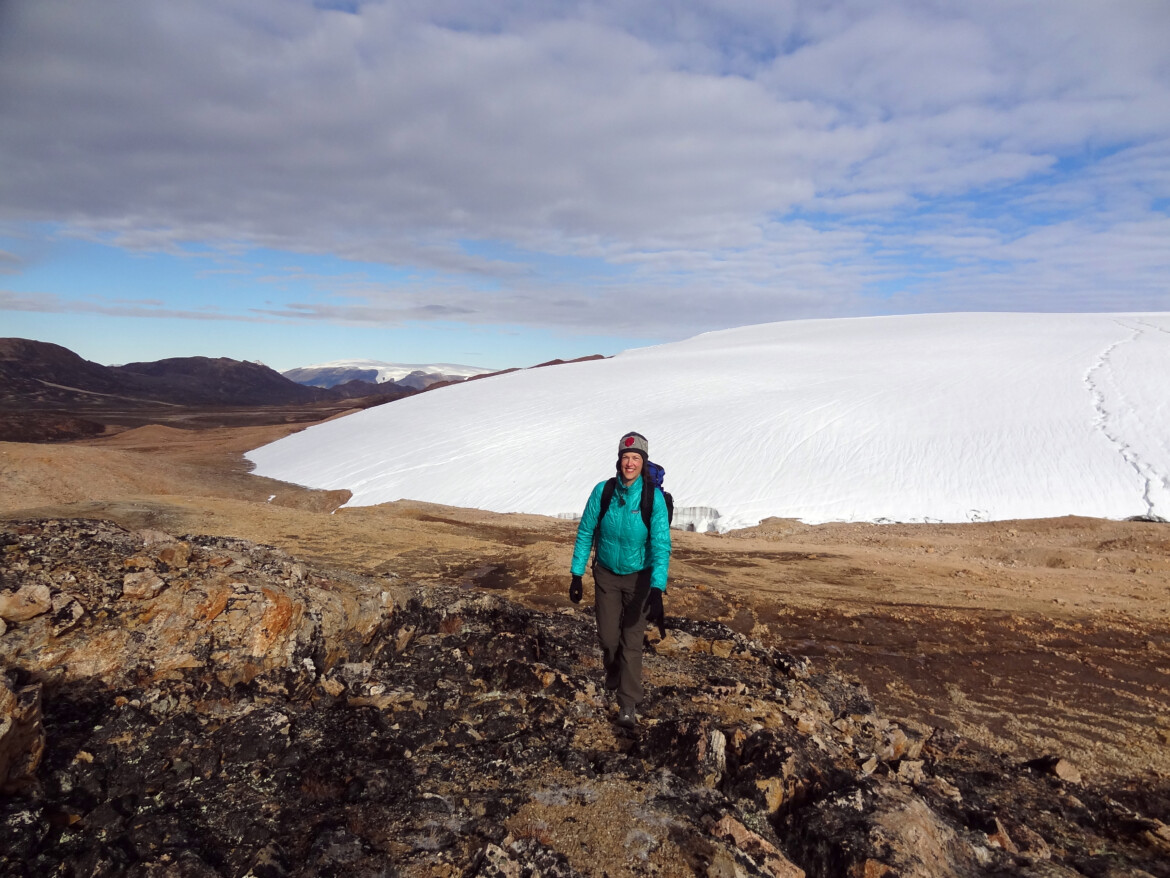

Berke on a sampling expedition on Lake Malawi, which is located in Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania. Credit: Josef Werne

A Depressing Job

In early January, a high-profile climate scientist named Eric Holthaus tweeted about stress caused by his job. “I’m starting my 11th year working on climate change, including the last 4 in daily journalism. Today I went to see a counselor about it,” the thread began. “I’m saying this b/c I know many ppl feel deep despair about climate, especially post-election. I struggle every day. You are not alone.”

I'm starting my 11th year working on climate change, including the last 4 in daily journalism. Today I went to see a counselor about it. 1/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

Holthaus wasn’t the only one noticing an emotional toll. For Yarrow Axford, an assistant professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Northwestern University, simply understanding the data can be a source of despair. “When you really dig into the science of climate change and start to learn a lot about it, I think the more you know, the more alarming it all is,” she said. “The facts are really devastating.”

Axford studies paleolimnology, which covers lake sediments and past lake environments, a concentration similar to Berke. She has made several treks to Greenland, where she takes samples from glacial lakes to learn about the past. As she reconstructs past melting speeds, something becomes startlingly clear: The glaciers are melting much faster than ever before.

It’s one thing to read that sentence, and another to see it happen. “They have had some personal experience witnessing changes in landscapes in which they’ve been doing their science,” Manning said. “So watching a glacier retreat, or watching an ice shelf collapse, or watching an ecosystem rapidly change unexpectedly, or watching coral reefs die — they have more of that firsthand experience than laypeople do.”

Yarrow Axford and her team on a coring raft in Greenland. The equipment shown is used to obtain samples from the bottoms of glacial lakes. Credit: Alex P Taylor

Witnessing the data playing out in real life can be traumatic, but Axford understands why so many people don’t feel the same sense of urgency she does. “One of the problems is, an awful lot of the impacts are way in the future,” she said. “We are seeing the impacts of climate change already, but it’s only going to get worse, and a lot of the worst impacts won’t affect us, or even our children, but generations beyond that. So, how do you really prioritize that above dealing with something like a war that’s happening in the present day to the present generation?”

Skeptical members of the public reflect that idea. Only 33 percent of Americans feel a “great deal” of worry about climate change, according to a 2016 Gallup poll. Forty percent of those surveyed said they worried “very little” or “not at all” about climate change.

Troy Lundstedt, a student studying construction engineering at Iowa State University in Ames, believes that humans are contributing to the rising temperatures, but thinks there are much bigger problems in the world. “I’m more worried about my home being vaporized by nuclear weapons, or about poverty and disease, because it affects us more in the short run,” he said.

His attitude is understandable. The Midwest is fairly insulated from the more widely recognized effects of climate change, like sea level rise and melting ice caps. Sure, there’s been a spike in extreme weather, and February was warmer than average, but for a skeptic, that doesn’t necessarily prove that global warming is happening. “Depending on your ideology, you interpret your experiences differently,” Manning said. “If you already think climate change is a problem and you get an extreme rainstorm, you think ‘yup, that was a climate change fueled rainstorm.’ If the rainstorm happens and you tend to endorse a conservative ideology, you’re less open to this being climate change.”

Even if a person does believe in climate change, the lack of personal experience makes it easy to ignore. “When climate change is an abstract, intellectual thing that you’ve only read about, and you’ve never seen it in person, it never attains that physiological jolt,” Manning said. “That’s why you also see all the people who say they’re concerned about climate change not actually taking much action to do anything about it.”

Public indifference gets exhausting for climate scientists. “It does, on some level, feel like pushing the boulder uphill perpetually,” Axford said.

But the recent presidential administration change is causing its own added layer of worry. While President Trump himself has been unclear about his views, his chief of staff Reince Priebus recently told Fox News that Trump’s “default position” is that “most of it is a bunch of bunk.”

Many of Trump’s decisions since taking office seem to reflect that ideology. He chose a climate change skeptic, Scott Pruitt, to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. His budget proposal removed $100 million in funding for the EPA’s climate studies. Just days after taking office, Trump signed an executive order removing restrictions on power plant emissions set in place by former President Barack Obama.

When Trump was elected, Axford vowed to give him and his administration a chance, and she still notes that he hasn’t been in power long. “But I will say, they have appointed so many very vocal climate deniers that I think their message about climate change is pretty loud and clear,” she said.

There are no commercial flights from the U.S. to Greenland, so Axford’s expeditions are made possible by the U.S. NSF and the U.S. Air National Guard. Behind Axford is a plane that took her and her team to Kangerlussuaq, Greenland in 2009.

A hostile presidency could limit the amount of work Axford can do, especially because she relies on the government to help her get to her research sites. Military aircrafts fly her and her research team out to Greenland — the country isn’t exactly accessible by car.

But beyond her own work, Axford worries about her students and younger colleagues. “They need to get into the field the first one or two years of their research careers and get some good samples that will allow them to do good work in the lab for a couple years,” she said. “If funding goes away in that narrow window for them, then they really need a plan B that’s very different. Because Arctic research is so dependent on significant public funding, that’s a concern I have for our students.”

Coping

Internet comment sections have no shortage of hate for climate scientists. Under a Washington Post article from December 2016, in which climate scientist Michael Mann discusses death threats he and his family have received because of his work, the very first comment is this: “I AM a scientist, and I know what true scientists do, and you, sir, are no scientist. You’re a propagandist.” Further down, someone posted “More Joe McCarthy of the Left diatribes. Useless, and most likely a hoax.” These are two of the gentler, less profane comments.

The nasty rhetoric is not just in the comment sections, though. “I can kind of personally vouch for it because I feel it myself,” Axford said. “Climate scientists have received death threats from members of the public. I’ve received angry emails from people at points when my work shows up in the media. It makes climate scientists, at least some of us, feel a bit fearful about being outspoken.”

That fear of being outspoken isn’t new, though. Axford remembers having conversations with graduate school friends in the early 2000s, trying to figure out whether or not it was safe to be an activist. She thinks eight years with the science-friendly Obama as president allowed climate scientists to let their guard down, but said that the backlash isn’t really new.

“I think the level of anger that’s directed at climate scientists by public officials is probably ramping up,” Axford said. It’s sort of less in the shadows and more out in the open, but it’s been there for a long time. Those of us who’ve been doing this for a while, we’re not strangers to any of this.”

An Airforce Greenland helicopter provides logistical support to Axford’s camp in northwest Greenland. The National Science Foundation provides funds for research trips like these.

Axford’s words have a familiar ring to them — Berke’s talk of “soldiering on” has the same air of “eh, we’re used to this.” She sites changes in Canada as an example of climate scientists’ resilience. As recently as 2012, Canada’s government was hostile toward climate scientists. They slashed funds for climate research, and closed one of the world’s most important Arctic research stations.

“The administration basically wouldn’t allow their climate change scientists to speak, go to conferences, and talk about climate change and what they knew about climate change,” Berke said. “But now they have an administration that is more open to listening to their scientists. They’re taking positive steps about climate change.”

Climate research may have slowed in Canada, but it never stopped. Berke said the same will be true for the United States. “Funding for students may be harder, and funding for trips to collect samples to show the change may be more difficult. But as a whole, the scientists are going to keep collecting the data, and we’re going to keep publishing the data and we’re going to keep telling people about the data,” she said. “I think as along as we still have people who are willing to do that, we’ll come out ok on the other side.”

Berke believes positivity is a climate scientist’s most important weapon. “You’re trying to be upbeat,” she said. You’re trying to say, ‘look, we know what’s happening, you know why it’s happening, so we know how we can make a difference.’”

Both Berke and Axford said they find some of their greatest hope in younger generations. “Little kids and not-so-little kids were growing up in a time where they heard all about this,” Berke said. “It’s something you can easily look up for yourself and see the data. Young people have done that. We have a much larger percentage of people trending towards knowing science, respecting science, and not thinking science and scientists are trying to do them any harm.”

Axford’s role as a professor keeps her motivated. “Every year, I get a new infusion of enthusiasm for learning and understanding from students, and I’m really thankful for that,” Axford said. “If I was purely a researcher, not also a teacher, I think it would probably be harder to deal with all of this. It is just so wonderful to meet new young people who are interested in understanding our world.”

Understanding the world is a lofty goal. Now, it appears that the next wave of climate scientists will need to build an understanding with a doubtful public, too.