In its long history, corn ethanol has seen some highs and lows, but the best could still be yet to come

Picture this: the year is 1900. A horse trots down a poorly-maintained dirt road, its buggy and passengers in tow. Pedestrians, oblivious to the majestic creature galloping by, are distracted instead by an unknown metallic beast: the early automobile, graceful in its own right, cruising down the bumpy path before it.

Though a rare sight at the time, automobiles in the early 20thcentury would soon become the norm. And nearly a third of those emerging vehicles were estimated to have been powered by electricity.

That is, until 1908, when Henry Ford introduced his Model T, a gasoline-powered car that was affordable for the masses. And, with newly implemented roads literally paving the way for these efficient, chug-a-lugging, oil-powered machines, horse-and-buggies, as well as electric vehicles, became virtually obsolete.

The oil industry seemed unstoppable—so, too, did the greenhouse gases leaking from tailpipes into the air, trapping heat in the atmosphere and making the planet unnaturally warmer at an unsustainable rate. Though no one back then knew anything about such matters.

And tailpipe emissions were only a small piece of the problem.

“When we talk about emissions from gasoline and diesel, people are mostly thinking about the tailpipe emissions from cars and trucks, but actually there’s quite a substantial amount of emissions associated with extracting and refining oil,” says Jeremy Martin, director of fuels policy and senior scientist for the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Those are actually very significant emissions, and there’s substantial opportunities to reduce those emissions.”

Something needed to change.

A Foil to Oil

Farmers have always been innovative; they’ve been putting food on the table for centuries. In Midwestern states, where agriculture drives the economy, it’s especially critical to utilize crops in new ways to get the most out of high corn yields.

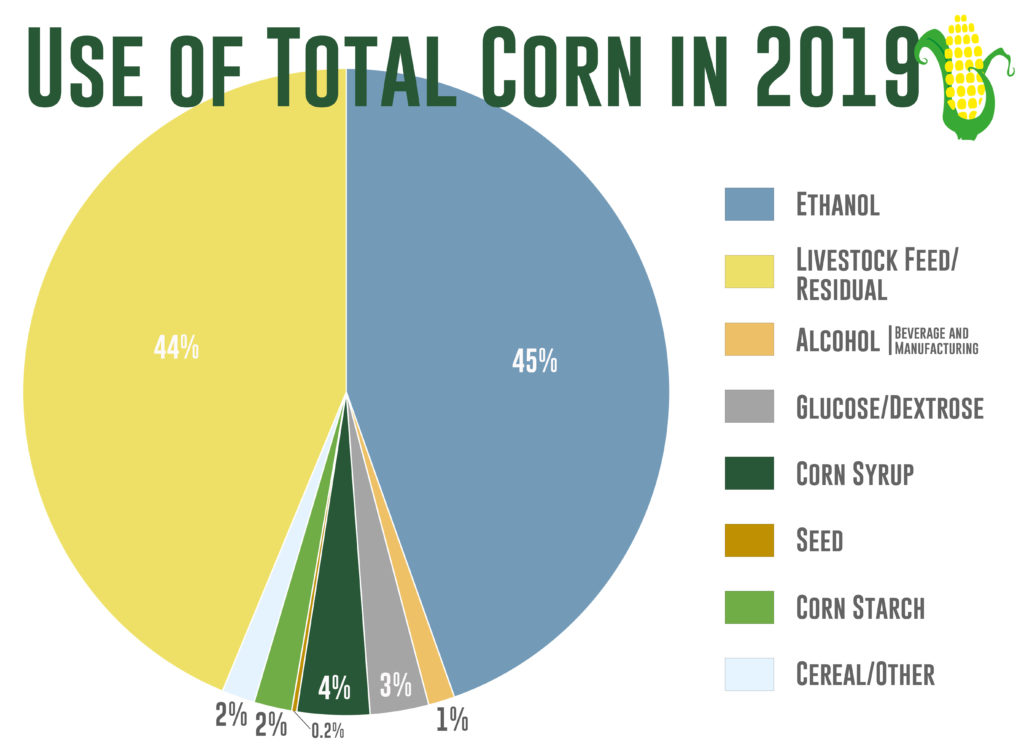

In 2000, corn for human consumption—in items such as cereal and high-fructose corn syrup—only accounted for about 9 percent of total domestic use of corn in the United States. Corn was primarily used for livestock feed, accounting for 75 percent of total domestic use at that time.

This was before ethanol entered the scene. Ethanol is essentially moonshine made into fuel. You take a grain like corn, ferment it, distill it into a grain alcohol, then toss in additives to make it unsuitable for human consumption. The end result: a renewable biofuel is created directly from living matter rather than oil.

During the early 2000s, primarily after the events of September 11, 2001, the U.S. made a push to rely less on foreign imports of oil. Robert Brown, professor of engineering and director of the Bioeconomy Institute at Iowa State University, says farmers had been experimenting with ethanol technology dating way back to the Revolutionary War. But ethanol production accounted for only a minute amount of the total domestic use of corn through the early 2000s—only 8 percent at the start of the decade.

“There’s a long history [behind ethanol], so it really wasn’t rocket science to say, ‘let’s go to large-scale production out of grain ethanol,’” Brown says. “It was not until about 2005 that there was a lot of debate about how to promote ethanol.”

That’s when the Renewable Fuel Standard was enacted with the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The Renewable Fuel Standard requires sources of renewable fuel, such as ethanol, to be blended with gasoline up to a certain percentage each year with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to global warming.

“[The U.S. Department of Agriculture] found that ethanol production reduces greenhouse gas emissions by up to 43 percent, which is much higher than when the industry first started,” says Cassidy Walter, communications director for the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association. “They also found that [biofuel] plants are getting more efficient every year. Not only does efficiency equal greenhouse gas reduction and environmental benefits, it also equals more money for plants, so they have a financial incentive to be more efficient.”

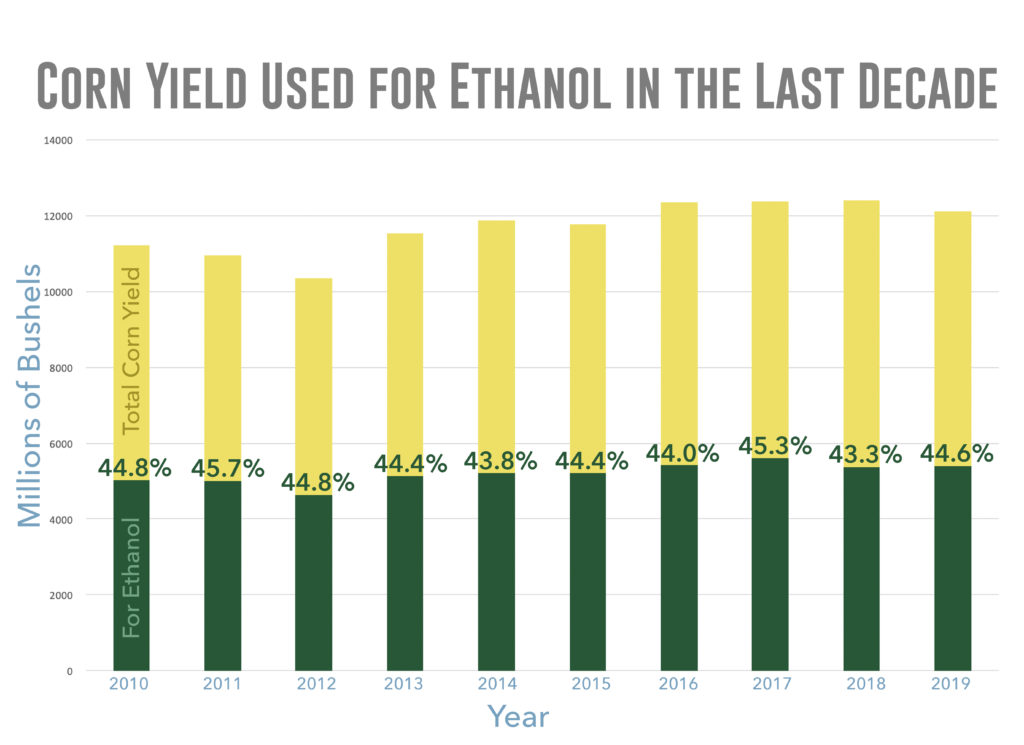

And farmers could now contribute to the transportation industry at a large capacity. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, since 2010, ethanol has accounted for around 45 percent of total domestic corn use each year, right up there with livestock feed, which now also sits at around 45 percent annually.

But there hasn’t been much growth since then.

“Since 2010, we’ve seen almost no growth in the use of ethanol,” Martin says. “As we look into the future, the prospects for increased use of ethanol are quite dim. By 2010, the country was using what we call E10; most of the gasoline sold in the U.S. today is 10 percent ethanol. But the prospects for going beyond E10 look very challenging.”

Gassed

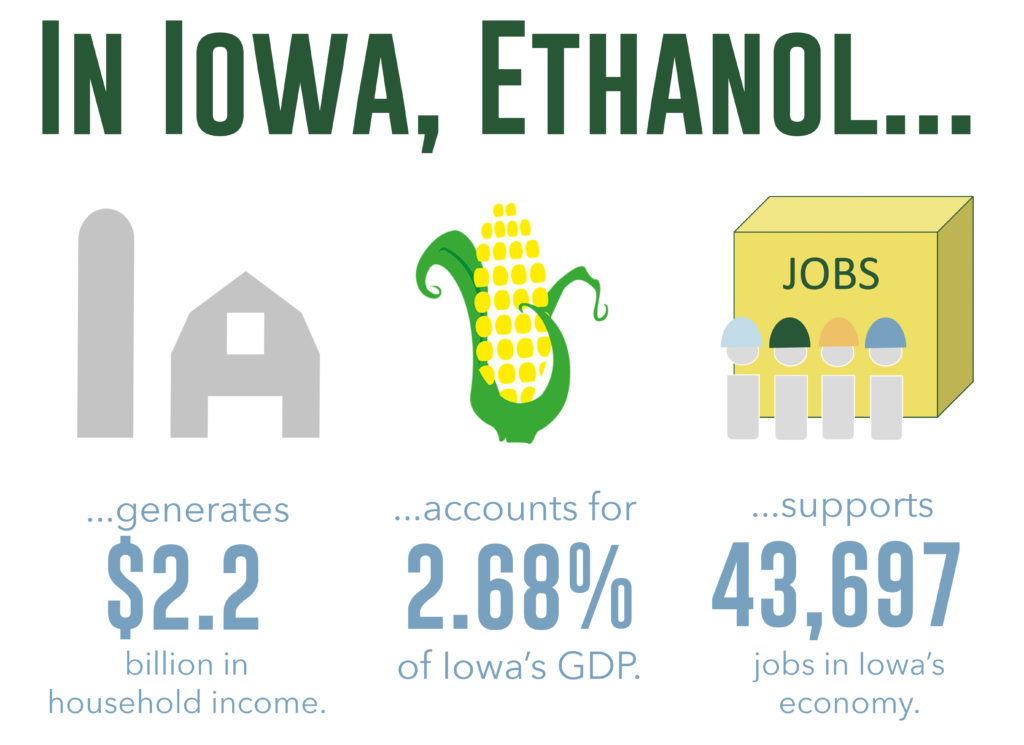

Agriculture drives the Midwestern economy, and ethanol now drives corn production. That means that ethanol production is a key contributor to the overall economy, especially in Iowa, the top producer of both corn and corn ethanol. Walter of the state’s Renewable Fuels Association says that ethanol production contributes around 43,000 jobs to the state, more than $2.2 billion in household income to workers, and $4.7 billion to Iowa’s gross domestic product.

So what’s the problem? The Renewable Fuel Standard, the same law that put ethanol on the map, now leaves it stagnant, unable to grow.

“There’s a law that says if you’re a small [oil] refinery, you can apply for what’s called a small refinery exemption, and these are on a yearly basis,” Walter says. “The other thing that’s important to know is when they grant these exemptions, whatever gallons that refinery would have had to blend if they were being required to comply with the law are supposed to be reallocated to all of the other refineries that are still obligated to comply.”

But in recent years, more and more of these exemptions have been granted, and even worse: the exempt gallons haven’t been reallocated to other refineries, meaning there has been a drastic loss of demand for ethanol. Things have grown so dire that around 30 biofuel production plants in the country have had to shut down production this year, including four plants in Iowa.

Making things even more difficult, farmers are doing their jobs too well.

“Obviously corn growers do a good job at what they do, and we do have a surplus of corn,” says Jim Greif, president of the Iowa Corn Growers Association. “There is roughly a 2-billion-bushel surplus of corn in the United States right now, and 1 billion of those bushels were caused by the small refinery waivers. So half of the surplus that we have right now is a direct result of small refinery waivers; it’s caused a huge impact on our income. Our net income’s down half what it was four years ago.”

And, sadly, Greif suspects that a large amount of these small refinery exemptions are actually being granted to subsidiaries of large, profitable oil refineries who would be able to comply with the law of blending ethanol into their oil without facing extreme economic harm. Instead, it is ethanol producers facing that harm.

As of May this year, it seemed like things were finally headed in the right direction. E15—a gasoline blend of 15 percent ethanol—was approved by the Environmental Protection Agency back in 2011. However, it was approved at a limited capacity, only available for cars introduced after 2001 to purchase from September 16 through May 31 each year, avoiding the summer months due to additional regulations and pushback from oil companies.

Now, the EPA has ruled to allow E15, often labeled as Unleaded 88 on gas pumps, to be sold year-round at fueling stations. But it remains slow to catch on, and the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association estimates that E10 still accounts for 97 percent of the gasoline used today.

Besides, it’s hard to celebrate this recent ruling in favor of increased ethanol production when the future of the industry still lies in the hands of the government and its exemptions. Farmers, like Greif, have their own solutions.

“The big one is just follow the law; the law is the law,” Greif says. “They’re required to blend the ethanol, and to put that billion bushels of corn back in play would go a long way. Some people don’t think they have to follow the law. Well, we think they should.”

A Spark of Hope

Picture this: the year is 2029. The telltale smoke of a gasoline-powered automobile has become increasingly difficult to spot on the street. Ancestors to the early electric cars of the 1900s have reemerged, but new-and-improved, available at prices competitive with gasoline-powered vehicles, and with a larger capacity for extended travel.

This is the future that Colin Cunliff, senior policy analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, says is possible in as few as 10 years, although it could still take decades for America to run primarily on electric vehicles.

Ethanol won’t be going anywhere anytime soon. But, already on shaky ground with current laws and regulations, the sustainability of the industry in the future remains largely unclear. Ethanol has proved its ability to minimize greenhouse gas emissions, but since it’s used alongside gasoline as a source of fuel, these emissions do still exist. And ethanol itself isn’t perfect.

“A lot of the carbon in the corn still is retained in the ethanol and is reemitted in the atmosphere when you combust it,” Cunliff says. “You use energy to convert the corn into ethanol in the first place. And then the fertilizer that you use to grow the corn, a portion of that evaporates as nitrous oxide, which is a very powerful greenhouse gas.”

Environmental policy experts, including Cunliff, believe that the solution to a sustainable environment would be to decarbonize the transportation sector completely—and that would be doable once electric vehicles are available at fair prices and with increased travel capacity.

However, farmers and the larger biofuel industry aren’t down and out. The needs of other sectors, such as long-distance shipping and aviation, will likely require liquid-based fuels for the foreseeable future.

“If you think about it, even if all the cars were electric, the demand to have a low carbon source of fuel for planes, for long-distance shipping, and things like that, that demand is much larger than what biofuels is producing today, but it’s a different set of products,” Martin says. “I think the biofuels industry will need to evolve over time to meet the needs of the transportation sector.”

And, as Walter points out, the gasoline-powered vehicles on the road today aren’t just going to disappear overnight.

“Even if the president were to sign an executive order that every new vehicle sold in the United States from today on had to be an electric vehicle, it would still take nearly 20 years for all the vehicles on the road today to turnover,” Walter says. “So if we want to take action today to reduce carbon in the transportation sector, we need to be utilizing biofuels and decarbonizing liquid transportation fuel.”

Even still, Greif says the possibility of a minimized role for biofuels and corn ethanol is on farmers’ radars, even if it’s just in the back of their minds. They’ve entertained the idea of ethanol-powered fuel cells to run electric vehicles, as that electricity still has to be generated somehow—and ethanol is a lot cleaner than coal, which is typically used to generate electricity. The details aren’t entirely worked out, but Grief remains optimistic that farmers will maintain some role in contributing to liquid-based fuels in an uncertain future.

“I wouldn’t say it’s an issue; it may be an opportunity actually,” Greif says. “One-hundred-nineteen years ago, most [vehicles] were electric. And then all of a sudden, Henry Ford comes along with a cheap gasoline-powered car and put all of the electric car companies out of business. That did happen almost overnight. But I don’t think it’s going to go the other way back overnight like that unless some major breakthrough comes through in battery technology. And then again, we still have to generate the electricity to fill those batteries up somehow.”

Ethanol as we know it today may not be the end-all be-all for the transportation industry. But farmers are along for the ride.

2 thoughts on “A Tell-All on Ethanol”