Iowa was invaded on October 12, 1863. Twelve Confederate guerrillas wearing stolen Union uniforms crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, riding north from Missouri into Davis Country, roughly two hours south of modern Des Moines. They robbed farmers and those walking to the county fair. They stole money, guns, horses, produce, and cigars. According to an 1865 report from the Adjunct-General of Iowa, they even ordered one man to take off his pants because they were Union blue. The soldiers also gunned down a farmer for refusing to obey them, shot former Union soldier Eleazar Small in the face, and killed Captain Philip H. Bence of Company F, 30th Infantry, before they fled back south to Missouri.

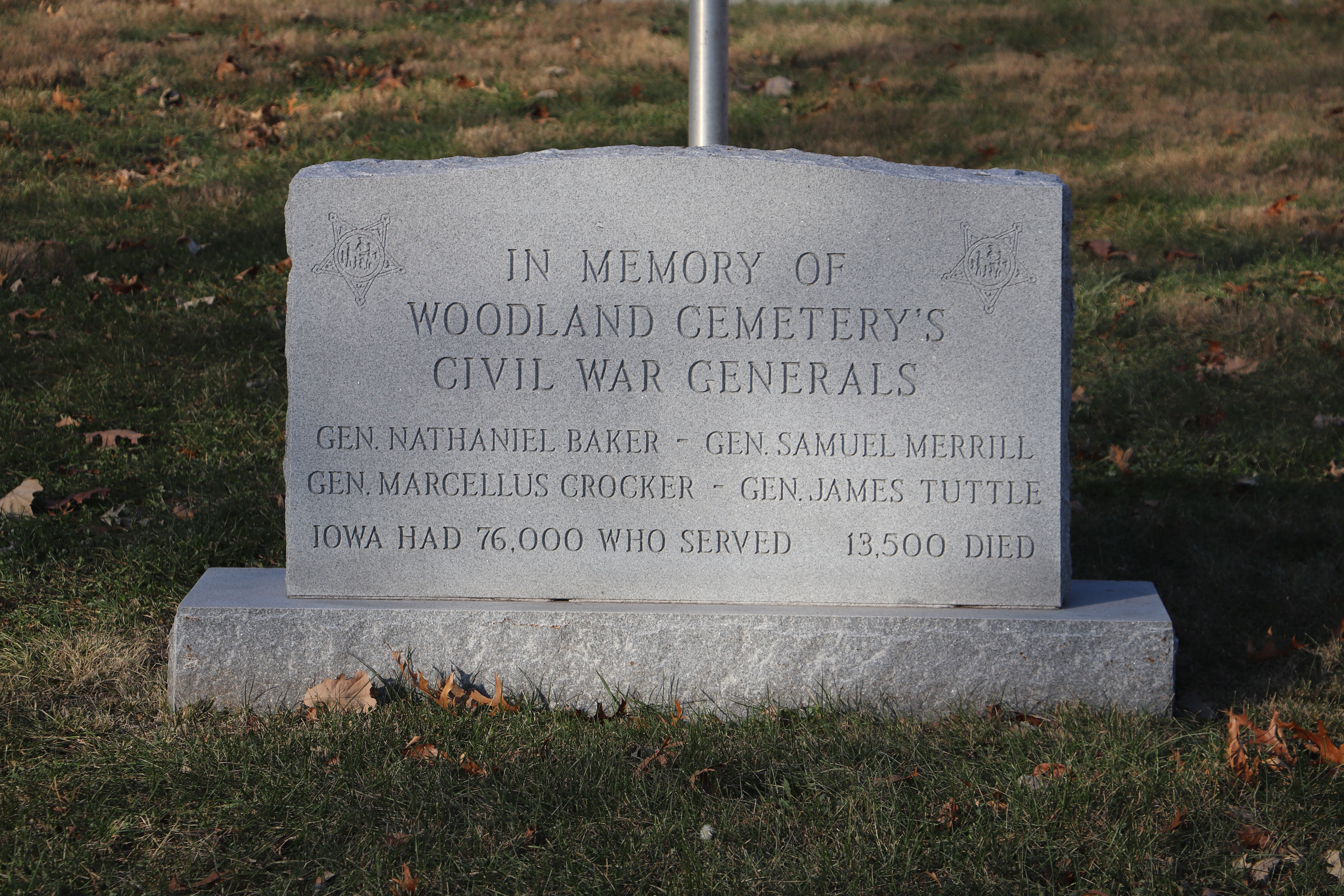

Those were the only three Civil War deaths in Iowa, though they weren’t the only Iowans to die in the war. By the time the Civil War ended, 76,534 Iowa men had served in the Union army, meaning Iowa, relative to its population, sent more troops than any other state to fight. And despite not a single major battle taking place in Iowa, 13,169 Iowan men had been killed.

But those three Davis County men—and the Confederate soldiers that killed them—are the ones that ended up with a monument. It was erected in 2005.

Civil War Monuments Now

Confederate monuments have been in the national spotlight for the last several years. The debate started after Dylann Roof killed nine people at a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina. Over the next couple years, protests and political forces led to the removal of several monuments in states like Louisiana and Alabama, pleasing some and angering others. The controversy peaked last year when groups linked to far-right movements gathered to protest the removal of Confederate names and monuments from a public city square in Charleston, culminating in the death of a Charlottesville woman. Conversations surrounding the merit and necessity of these monuments have continued.

For many Midwesterners, this debate feels far away. It’s not. Most might be surprised to find that any sort of commemoration for Confederate forces can be found this far north at all. In Iowa alone there are two: a small marker in Bentonsport and a monument in Bloomfield.

The Bloomfield monument erected in Davis County consists of three stones, two flagpoles, and a plaque, which states that the structure serves to mark the northernmost point of incursion into Iowa by Confederate Forces. It was dedicated by both the Iowa chapter of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW), and the Iowa Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), and if you didn’t know what it was, you might just drive by without a glance.

Working Together to Preserve History

The number of Civil War monuments today continues to increase annually. While this is partially due to new monuments being erected, monuments and grave markers that were previously lost to time are continuously being discovered and documented. They’re usually found thanks to the historical investigative efforts of groups like the SUVCW and SCV.

This isn’t to say that all the documentation continues to be completed by each side for only their side’s history. As Commander Charles Lott of the Iowa SUV says, many efforts transcend the opposing namesakes of each organization to help contribute to the greater motive of preserving history.

“They have probably marked or discovered 60, at least 60, Union graves that hadn’t been marked. So you know they’re not … they do as much as we do here in the state of Iowa trying to mark the graves of all the Civil War soldiers.”

The SUVCW and SCV give continual efforts to maintain the integrity of monuments and grave markers dedicated to veterans of both sides of the Civil War in Iowa. The groups point to another source of purpose that drives them: the meaning behind physically being there to remember the individuals who passed.

For Commander Lott, the focus on individuals remains central to his motivation for taking part in the organization. It also explains why he believes that monuments such as the one in Bloomfield, which commemorate events that took place on the spot they now stand, should remain there.

Why Location Matters

When Confederate monuments are located on public property, like many currently being protested in the South, their future is more uncertain than those located on private property, like the one in Bloomfield.

Some historians and activists involved in the developing conversation feel like a key point of their hopes for the future of these monuments continues to get lost in the noise enveloping the issue. They don’t always want to see these monuments destroyed. They believe that relocating the more controversial statues into a museum setting and adding more historical context might refocus the intention of these memorials to educate about local history instead of continuing to spark controversy.

Moving monuments without looking more into the history of why it’s located where it is might have unintended negative effects, according to Commander Danny Krock of the Iowa SUVCW.

“I can’t really describe the feeling, but it’s very moving, and it really changes your perspective on things. Just to see it. To walk the same ground that they walked is amazing.”

From both their perspectives, monuments that seek to memorialize an event that took place on the location they mark need to stay on location for their full effect to be felt and for the individuals they seek to commemorate be remembered.

The Evolving Conversation

As many continue to discuss the influence and value of Confederate monuments, Veronica Fowler, from the Iowa branch of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), says she hopes we only continue to discuss as a country what we want for the future of these memorials.

“These sort of Confederate monuments have just sort of always been there, and I am heartened by the increased discussion about how they should be treated. And increasingly governments are taking them down. And again, we (the ACLU) are not advocating for their destruction, we don’t want to erase history, but we want history put in context.”

Hopefully, that context will allow for a more informed and accurate conversation around the war, slavery, and the Confederate monuments in the Midwest and elsewhere.