Words by Jenna Pfingsten

Photos by Kylee Bateman and Jenna Pfingsten

Video by Kylee Bateman and Becca Jonas

Osage City, Kan. — The smell of freshly cooked barbecue is unmistakable as you enter the Smoke in the Spring barbecue competition. The meaning behind the name becomes clear as soon as you walk past the cooks working on their entries: Smoke permeates the open fields, visible against an overcast sky.

This is Smoke in the Spring’s 15th annual contest, attracting over 100 teams to Osage City, Kansas. Most are local to the Kansas City area, but some have come from as far as Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Texas. On Friday night, the community came to try the barbecue and enjoy live music. But now it’s Saturday, and the teams are finishing up the meats that’ve been cooking all night. Yesterday was fun, but today it’s crunch time.

Contrasted with grilling, which is cooked quickly over direct heat, barbecue refers to meat that is cooked slowly over low, indirect heat. There are two main ingredients in barbecue—wood and meat, with sauce as an optional third ingredient.

The process of barbecuing meat over an indirect flame has been around since the 1500s, and has since become a staple of American culture. Different parts of the country have their own style of barbecue, but the basics stay the same no matter where you go.

Barbecue competitions started around the 1950s or ‘60s and have grown into a livelihood for many people. Since cooks are the ones outside doing the work, they get a lot of the recognition at competitions, but it takes a passionate group of people to eat all of the food and pick out the best of the best.

The Barbecue Way

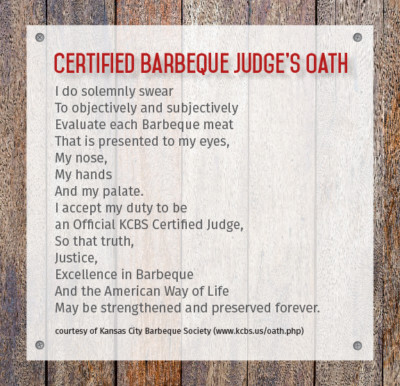

It’s not hard to get certified to judge barbecue. You’ll have to get involved with an organization that sanctions barbecue contests and provides classes to certify judges. One prominent organization is the Kansas City Barbeque Society (KCBS).

With over 20,000 members and nearly 500 contests a year, KCBS is the world’s largest barbecue organization. It started in 1986 as a way for cooks to stay connected and hear about new contests. The only requirement to join was that none of it be taken too seriously. Since then, KCBS has grown into a bigger business with stricter guidelines.

“It was a mom-and-pop business, and then it started growing into bigger money, more people. At that time it was around 400 members. And then they decided, we ought to have a judging class,” judge and instructor Bunny Tuttle says.

Tuttle was part of the first judges class—her judges number is 14, and her husband, Rich, is 13. She got into teaching a few years later as a way to combine her love of teaching with her love and knowledge of barbecue.

The classes discuss the history of KCBS and the differences between types of meats, but the most important things students learn are the KCBS standards for judging. You judge appearance first, looking for how tasty the meats look. Next you judge the taste and tenderness as you take bites of each piece of meat. Each entry is given a score between 2 and 9 for the three categories, with 2 being inedible, 6 average, and 9 excellent.

The judging process is straightforward enough, but the tricky part is judging each piece of meat fairly and not comparing them to each other. Each piece of meat is judged on its own merit and not ranked against the other pieces.

“You follow the example of the standards that we set forth in the class. And when you do that, you only judge what’s in that box—that’s being objective,” Tuttle says.

This means a judge can’t give a lower score based on their own preferences. Whether or not they like dark meat, burnt ends, or sweet sauces, they have to give it a fair score—personal opinions are left in the car. The standards also dictate that the appearance of the garnishes, like lettuce and parsley, can’t factor into the scores.

“We don’t judge salads here. We judge meat,” Tuttle says.

After learning how to be an objective judge, students get the chance to put their new skills to the test with a few rounds of practice judging. Volunteers pass out boxes for each table to score on appearance, taste, and tenderness. After each round, the class discusses the pieces of meat in detail, explaining why they gave them the score they did. Ribs get a lower score in tenderness for falling completely off the bone, but would score higher in taste if that extra cooking time gave them more flavor. A box with chicken would get a good appearance score if all of the pieces were uniform, and brisket scores higher in tenderness if it pulls apart with a little tug.

“I’ve been out there in the field, tasted so many different cookers’ things, and I do know there are different flavor profiles. I know that there are different ways of cooking things that can be just as good,” Tuttle says. “I also know what’s really bad, what they’ve done wrong. I can almost taste it.”

The best way to refine your palate to taste the different flavor profiles is to eat and judge more barbecue. After the class finishes and students take the judge’s oath, they’re certified and ready to judge at a real contest.

The Big Leagues

As the clock ticks its final seconds before the cutoff time, cooks hustle to turn in the meat they’ve been laboring over day and night. Once the cook passes it off, it’s out of their hands—now it’s the judges’ time to shine.

The boxes are then taken to a table of six judges. It’s a blind judging, so no one knows whose food they’re tasting, and they’ll never find out.

This is the moment a barbecue judge waits for—when the boxes are opened and they get to see the labors of love awaiting them. Pieces of chicken that look like glazed rolls. A rack of ribs sitting on a bed of parsley. Brisket with a black bark and a pinkish smoke ring along the top. Table captains show the open box to each judge in turn, with a brief nod signaling the box can move on to the next person.

After all of the boxes have been scored on appearance, the judges pass them around, taking a piece from each box and placing it on their “plate,” which is a piece of cardstock sectioned off and labeled for six pieces of meat and decorated with the KCBS logo—all printed with edible ink. Once everything is plated, it’s time to eat.

There are no forks in barbecue—everything is handled with your hands, and the tables will go through a roll or two of paper towels by the end of the day. Once the judges start tasting the food, being objective gets hard.

“That to me is very hard to do because everybody, everybody, compares in life, and that is the hardest thing to do, to judge something on its own merit,” Tuttle says.

It’s quiet as judging gets underway. Low voices and the crinkle of styrofoam are the only sounds now, contrasted with the excited energy of the room five minutes ago. Judges eat slowly and intentionally, some closing their eyes to focus on the experience of the flavors. No doubt this is the highlight for most judges—the food they get to taste is from some of the best cooks in the country.

“It’s amazing some of the food these people produce because they’re not just cooks, they’re chefs. The flavor profiles and the way they mix things up together is wonderful,” judge Patty Kump says.

As barbecue competitions become more established around the Midwest and across the country, the stakes get higher. Bigger competitions have a bigger payout for the winners—some tens of thousands of dollars. The judges are the ones who have a say in who takes home that money, and they don’t take that responsibility lightly.

“I think the best part is actually helping the cooks achieve their goals because this is a competition for them, and they spend a lot of money, and they take it very seriously,” Kump says. “And I take it very seriously, because that’s who we’re doing it for, we’re doing it for the cooks.”

Barbecue Family

Barbecue has the ability to bring together people from all walks of life. It doesn’t matter what you do during the week or how experienced you are. During the competition, you’re a barbecue judge, just like everyone else.

“We have people all the way from 16 to before they die. And we have doctors, truck drivers, garbage guys. We’ve got lawyers. We’ve got everybody involved in barbecue judging,” Tuttle says.

This is Dodge Slead’s second competition. At 16, he was younger than the average age of the room by a few decades.

“It makes you want to learn from them, go to people if you have questions, find them. It’s kind of nice because then you can learn what things to look for that I might not see and they’ll be able to see,” Slead says.

This competition is made up almost entirely of master judges, so there are a lot of people to learn from. A judge becomes a master judge after judging 30 competitions and cooking with a team at least once. It’s a prestigious title and proves that you know what you’re doing.

It’s was never a question of if Slead would be a judge, but when. His grandparents have been involved with KCBS for many years, so Slead grew up around barbecue, going to competitions with his grandparents on weekends. He got certified last year when he turned 16, the minimum age for being a barbecue judge.

“When I went to do the barbecue judging class and table captain, I basically already knew everything. I’ve been able to be a table captain or judge for a long while; I just wasn’t old enough,” Slead says.

For a lot of judges, barbecue is a part of their family. Husbands and wives travel around the country judging together, or parents get their children involved when they turn 16. For others, a barbecue competition is where they find their barbecue “family.” Good food might be what brings them in, but the community is what keeps them coming back.

“Everybody in the society is barbecue family, and we all have something in common,” Tuttle says. “The best part hands down is family.”