Story by Jess Lynk and Katherine Bauer | Photos by Genna Clemen | Videos by Katherine Bauer and Genna Clemen

Originally published on April 13, 2018.

OVERLAND PARK, KAN. – Four years ago, a white supremacist opened fire outside a Jewish community center and nearby Jewish retirement home in a Kansas City suburb. He killed three people: Mindy Corporon’s father, her 14-year-old son, and Jim LaManno’s wife.

Hours after their deaths, Mindy stood before a crowd of shaken, reeling mourners to deliver hope and healing. The message that she started, a message that Jim helped spread, rippled throughout the community in the years that have followed.

This is a multi-part, media-immersive story that may take a while to download. Please be patient while files load.

On April 13, 2014, Frazier Glenn Miller (also known as Frazier Glenn Cross) targeted the Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City and Village Shalom, intending to kill members of the Jewish community. None of his victims were Jewish.

All times are approximate, as recounted by various witnesses, 911 calls, and accounts from Miller during the trial.

Jewish Community Center, 5801 W. 115th St.

10:30 – 11 a.m. Miller drives to the Jewish Community Center three times to look at the location. At one point, he decides to go home. Eventually, Miller turns around to return to the Center. Miller had a pistol, two shotguns, and a rifle in his car.

12 p.m. Terri LaManno leaves for Village Shalom.

12:45 p.m.: Reat and William leave for the Jewish Community Center

1 p.m. Miller arrives at the Jewish Community Center and heads toward the parking lot of the White Theatre. Miller shoots William J. Corporon and Reat Underwood, who are getting out of their red truck. Miller leaves the scene and drives to Village Shalom.

1:03 p.m. Police dispatchers receive calls of shots fired at the Jewish Community Center.

1:08 p.m. Mindy Corporon, Reat Underwood’s mother and William Corporon’s daughter, arrives at the Jewish Community Center.

Village Shalom, 5500 W. 123rd St.

1:15 p.m. Miller drives to Village Shalom, where Terri LaManno is getting out of her car. Miller shoots her.

Maggie Hunker calls 911.

Valley Park Elementary School, 123rd Street and Lamar Avenue

1:20 p.m. Miller drives to Valley Park Elementary School. He calls 911, but can’t reach police dispatch as all the lines are busy. He sits and waits for the police to find him.

2:45 p.m. Two officers notice a car and a man matching the description witnesses gave at both scenes. Police arrest Miller in the parking lot.

The Locations

From the start of Miller’s attack to where he was arrested, Miller drove a total of 1.8 miles.

View the route he took on April 13, 2014:

William Corporon died at the scene. Terri LaManno died at the scene. Reat Underwood was declared dead at the hospital.

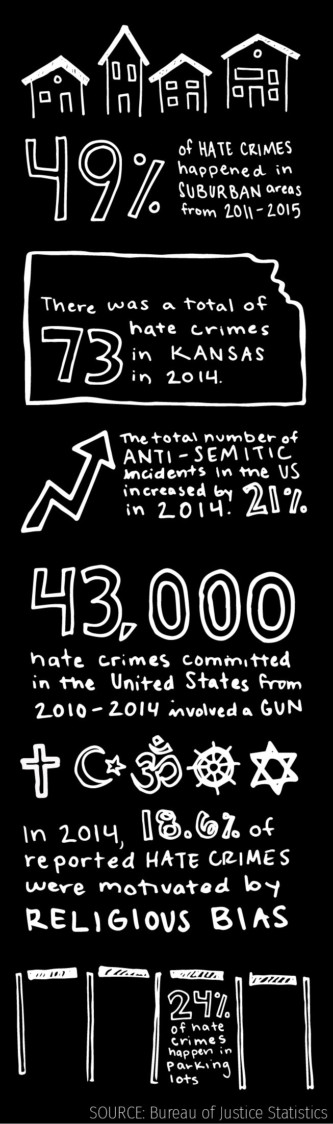

What happened in Kansas that day was rare. In 2014, this shooting was the only anti-Semitic hate crime that resulted in murder, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s 2014 audit.

But the motivation behind the crime wasn’t unusual. The same year of the offense, 1,092 reported hate crimes were motivated by religious bias, according to the FBI. Over half of the attacks targeted members of the Jewish community.

However, what transpired in the days following the shooting was extraordinary. Overland Park, Kansas, came together to find light in this hate crime.

Recovery started with remembering the three victims who died.

Terri LaManno helped people see. She helped the visually impaired, the kids who typically slipped through the cracks. Today, the world sees Terri’s powerful legacy.

After raising her kids, Terri went back to school and became an occupational therapist in 2002. Four years later, she joined the team at the Children’s Center for the Visually Impaired.

“Terri was a very dynamic person,” Terri’s husband, Jim LaManno, says. “Very goal oriented and very intelligent. … She dove into everything. She did everything right. She dove into her career, she was well-read, she was the type of person that you would want to be around.”

Terri worked on the infant home visit team for six years, visiting families to start occupational therapy with children. After that, she moved to the school run by the center.

During one home visit, she encountered an infant struggling to breathe. She asked the infant’s family to call 911 and immediately started CPR until paramedics arrived. The baby survived.

Terri’s brother said at Terri’s funeral – “She would much rather talk about you. She was interested in how you were feeling and in what you had to say.”

Terri was 53-years-old when she died. She had three kids.

“She was a—there is so many words— she was a fiercely loving and loyal wife and mother,” Jim says.

Jim and Terri were just starting a new chapter.

“… We had done everything that we needed to do,” he says. “We had got our kids all the way through college, and now we were going to start a different kind of life with some traveling and doing some things, so I lost kind of my partner and my best friend. A part of me was taken away. And part of our time together was taken away, growing old together and having kids, and grandkids, part of your life that goes away. And it goes away, in an instant.”

The day it all changed

Terri was late that day, but that wasn’t too unusual.

“I wasn’t really concerned at all,” Jim says.

But then two Overland Park police detectives came to his door.

“It was kind of a blur.… It’s almost surreal,” he says. “You don’t expect news trucks to be pulling in front of your house and people getting on Facebook to look us up … But a lot of positive things came from that.”

Terri’s Husband – “Part of our time together was taken away, growing old together and having kids, and grandkids, part of your life that goes away. And it goes away, in an instant.”

Jim, a dentist in the Kansas City area, says his work helped him cope with his loss. Going back to work helped him feel more productive and showed him the support of the community.

Jim says, from the beginning, the Overland Park community was supportive. Around 3,000 people attended Terri’s funeral.

“The outpouring of everything was unbelievable in this city,” Jim says. “… It was unreal, the outpouring. It was very, very public.”

Strength in Numbers

After Terri’s death, funds came in to the Children’s Center for the Visually Impaired from around the world. Jim and the center set up a scholarship to help two children, chosen by the center and Jim, every year. “So often is that the children who are sent there, their school districts don’t actually have enough money to support the kids and they lose kids through the cracks,” Jim says.

The scholarship fund helps pay for tuition for the Children’s Center for the Visually Impaired, which allows for these kids to stay in school.

Jim also set up scholarship funds at Terri’s high school and college. The scholarship funds in her name have accumulated $160,000.

“I knew something good would come from it, I just wasn’t sure how it would all play out,” Jim says. “But I am happy and joyful that this good came out of this. Terri was a very popular person. People liked her, and so I think when the news got out about her and who she was and what she was doing, I think people said, ‘Yeah that’s the kind of woman that everyone should want to be.’”

Jim wrote thank you notes to everyone who reached out to him after his wife’s death. To this day, he still writes notes to people who donate.

Life after April 13, 2014

Four years have passed, but the struggles haven’t.

Current events remind Jim about the hateful act four years ago.

“I saw the man who lost his daughter down in Parkland, and I know how he feels,” Jim says. “I didn’t lose a daughter, but I lost my wife. Let me tell you, it’s the same thing. I can see in his face. I know exactly what he is going through.”

Jim recognizes that there is a difference between the shooting that killed Terri and some of the other shootings in the news.

Frazier Glenn Miller “was just a bitter man, where I think that some of the other shootings where people are just mentally disturbed,” Jim says. “The man who shot Terri and the Corporons —he was just—he was just a racist, and he wanted to prove some odd point on people he didn’t even know.”

But each new shooting reminds Jim of what he believes should be done to fix gun violence in this country.

“… What we really need is education,” Jim says. “Educating people is where we need to be because somewhere along the way, we’ve lost it. I believe an education in this country is what makes people think more critically and we have people who are less rational about a lot of things. … Because without education, we really have nothing.”

Terri’s Husband – “I didn’t lose a daughter, but I lost my wife. Let me tell you, it’s the same thing. I can see in his face. I know exactly what he is going through.”

Moving Forward

Lately, Jim has adjusted to his life.

“I have to do everything myself,” Jim says. “It is kind of the mundane things in life that you take for granted, that you have to redo in your life. You don’t realize how much a person does until they are gone.”

On the anniversary of the shooting every year, Jim goes to Mass and to Terri’s gravesite

“I think back on what I had, but then, I know that she would want me to move forward, so I have to look forward to the future of what I am going to do,” Jim says. “I still struggle with that at times … but at some point it is obviously going to go behind you. It kind of has to, to a degree.”

The news trucks have stopped showing up to Jim’s home, but he is not done talking.

“I feel like I am here because she wants me to do this,” Jim says. “If it were me, I believe that she may be doing the same thing.”

April 13, 2014, changed Jim’s life forever. Even though he lost his best friend, he was instantly bonded with another family in Kansas.

On that day, Mindy Corporon knew exactly what Jim was going through. From then on, they have helped each other.

“We have helped pick each other up…,” Jim says. “Mindy has been, she is a godsend. She has energy. She’s really out there, almost every day, spreading our word. … We want people to understand that we have to change a little bit in this country. We can’t keep going on like we’re going.”

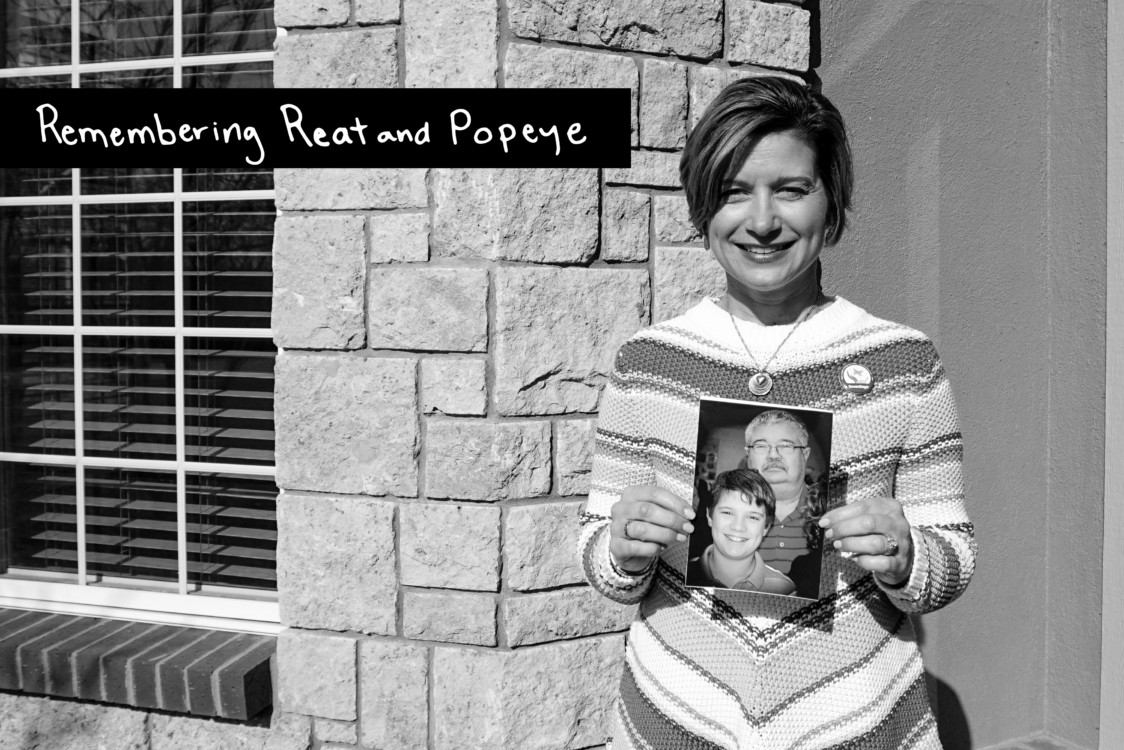

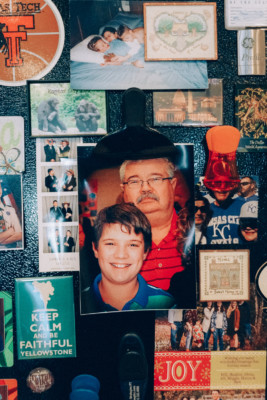

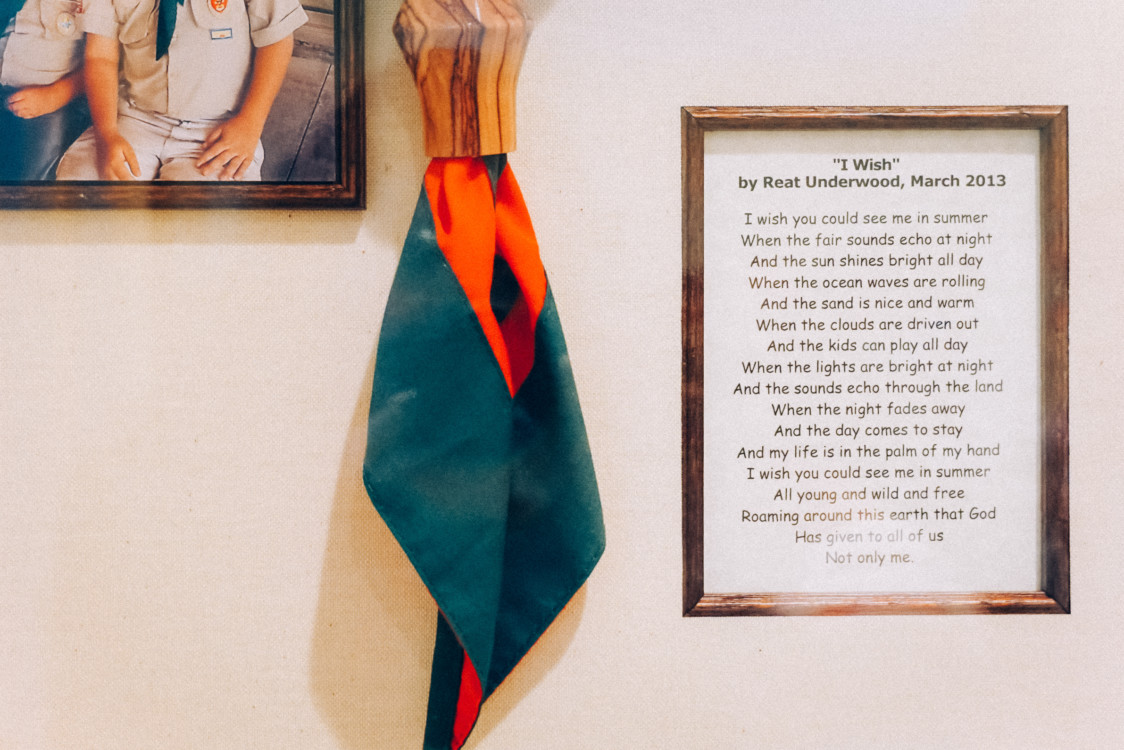

On April 18, 2014, Lukas Losen stood at the pulpit of the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection. At 12 years old, he delivered a eulogy for his 14-year-old brother, Reat Underwood, and his grandpa, William Corporon. Every seat was full in the 3,500 seat auditorium.

“These men were the most fun and caring of all our family and friends,” Lukas said. “… I cannot express my feelings for what is going on right now, but I love each and every one that is here today, especially my family and God. I love you Reat and Popeye. You will always be in my heart.”

WATCH: The full video of the funeral.

Five days before, Lukas’ older brother and grandpa were murdered at the Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City. William was taking Reat to an audition for Kansas City Superstar, a singing competition that awards a scholarship to the best high school student in the Kansas City metropolitan area. This was the first year Reat could compete.

It made sense that William drove Reat to the competition. Reat and his grandfather were inseparable. They both loved the outdoors, theater, and their families.

“It is just so interesting because Reat and my dad were very, very close,” Mindy Corporon says, daughter of William and mother of Reat. “He was a wonderful mentor to Reat.”

She lost both her dad and her son that day, but her love for her family is just as strong today.

“I tell people that — above me and below me — my dad and Reat, were my people because we have the same smile and we have the same eyes,” Mindy says. “… They were both my huggers. I can still feel my dad hugging me on occasion, and then Reat became my hugger, too.”

William was a doctor. Reat was a student at Blue Valley High School. When Reat was younger, he nicknamed William “Popeye.” Both of them had hazel eyes, like Mindy.

Popeye the Savior

“I would have been the one driving Reat,” Mindy says, recalling that Saturday morning. “I was almost always the one who drove Reat to anything that he went to.”

William protected Mindy many times throughout her life.

“He rescued me so many times during my life, which was amazing and fantastic,” Mindy said. “As an adult, I really started to see how a parent gives up for a child because I saw it with my dad.”

When she was in high school, William rushed to pick up Mindy after a rough day. In 2003, he left his medical practice in Oklahoma to move to Kansas to be closer to his grandkids.

He saved her again on April 13, 2014.

Mindy’s father was her hero.

“I know so many people can probably say that their dads are great, which is awesome, but I am the only girl in the family. I have an older brother and a younger brother, so I was definitely Daddy’s girl,” Mindy says.

William’s dad was a pastor. On occasion, Mindy said, William would preach when the pastor was gone at their church.

“I think he was a very good mentor about being able to speak and share who he was,” Mindy says.

She credits her dad for her public speaking skills. On April 13, 2014, she used those skills when she spoke at a vigil, just hours after his and Reat’s deaths. Since that day, Mindy has spoken to a variety of crowds, including at a vigil and a press conference within 24 hours of the shooting.

The Yoda Baby

“When [Reat] was born, my dad sent out an email saying, ‘Mindy just had her baby, and he looks like Yoda,’” Mindy says. “It was really funny. He did, he looked like Yoda when he was born. And I thought that was because he was going to be really wise or something.”

From the beginning, Mindy realized that Reat was intelligent. He memorized books that she read to him at the age of 2. He then started performing the stories.

By the age of 4, Mindy put Reat in a theater program. Reat loved to sing and perform.

“He was a singer and a performer and an actor, but he hadn’t quite been in very much dance,” Mindy says. “He started taking some dance lessons, and when he made Starlight STARS, and I think he just really felt accomplished because he had just had the trifecta then.”

This video of Reat singing the national anthem was played at a Kansas City Royals game on June 7, 2014. The University of Oklahoma also played the video on February 28, 2015, 10 months after Reat was killed. Singing the national anthem at a University of Oklahoma basketball game was one of Reat’s lifelong dreams.

Mindy says he loved cheese, in particular stinky cheese. He eventually wanted to open a cheese shop.

“He was just a fun, unique kid,” his mother says. “I learned so much more about him after his death from friends because I didn’t know how he was in school.… But the letters that I got, from friends and from parents of students who said, ‘My child came home today and told me how important your son was to them.’… Those were very, very special. I think he was super special.”

Reat was really important to Jake Svilarich. Jake and Reat met in fifth grade, after Jake moved to the neighborhood. They had classes together in middle school, and a friendship started.

“[He was] a fun clown,” Jake says. “He just cracked jokes all the time and was always real upbeat. He would sing anytime a song came on, it wouldn’t matter what it was. He would try and figure it out. He was just a lot of fun to be around and really uplifting. He was a good guy.”

Jake lost his best friend as a freshman in high school.

“The weeks after, everything was real quiet. It sucked,” Jake says.

The Weeks After

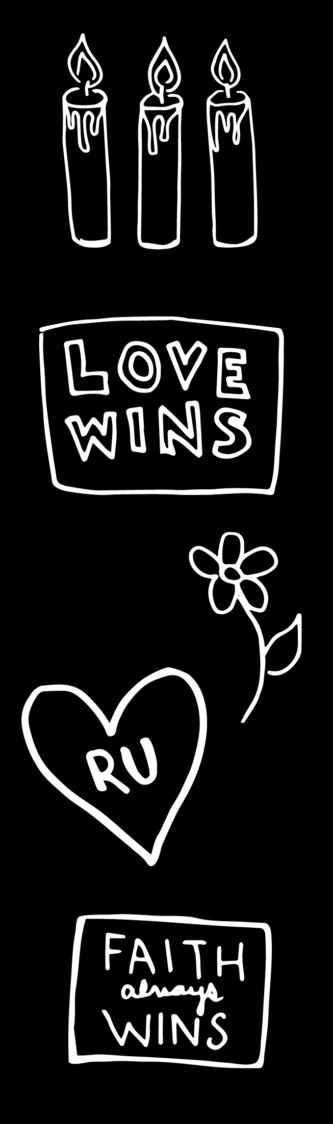

On the way to Reat’s funeral, his family were met with a line of people dressed in white. The crowd had signs that said things like “Love Wins,” “Remember Reat,” and “Remember Popeye.” “You just don’t ever want to be in a car on the way to your child’s funeral,” Mindy says. “It shouldn’t happen. I kept thinking that this should not be happening. And it was for my dad and my son.” Even though the circumstances surrounding William’s and Reat’s deaths were hateful, Mindy wanted to celebrate their lives at their funeral. “My dad was 69 and certainly should have lived into his mid to late 80s,” Mindy says. “Reat was a baby when you look at it.… He seemed so grown up at the time, and I know he felt so grown up as a freshman, but when you look at life’s longevity that he should have had, he was just a baby at 14.… We just didn’t want this to be a funeral, and we didn’t want to feel like a horribly sad funeral, and we wanted people to celebrate their lives.” It felt like a celebration when they saw the line of people supporting them. They continued to see that support in the coming weeks and months, but that didn’t make the pain go away for Mindy and her family.

Mother of Reat Underwood and Daughter of William Corporon – “You just don’t ever want to be in a car on the way to your child’s funeral.”

Restoring Routine

Mindy had trouble simply getting to the mailbox in the weeks after the shooting.

“There were so many things that I wanted to do, but physically I just couldn’t do them,” Mindy says. “… I just had trouble physically walking for very long.”

Lukas also struggled.

Lukas described a time where he hid Reat’s Nerf gun and how much they loved playing together. Mindy described Reat as a great older brother to Lukas.

“I know his heart was broken,” Mindy says.

Mindy and Lukas both struggled with the missed milestones. Reat would have graduated from high school in 2017. That year was especially tough on the family.

“We pulled in an exchange student for Reat’s senior year because really it was pretty miserable without him, and the house was so quiet and Lukas needed a buddy,” Mindy says.

The exchange student helped pull Mindy back into Blue Valley High School, the school that Reat had attended. She showed up to everything: theater performances, sporting events and even graduation celebrations.

Lukas struggled his freshman year of high school, which would have been Reat’s senior year. After giving Lukas the time to grieve, Mindy and Lukas decided it would be best for Lukas to leave Overland Park, Kansas. Today, he attends a golf academy out of state.

“He is so happy,” Mindy says. “I am happy for him. Your parents will probably tell you that they are as happy as their saddest child.”

Mindy’s 9 to 5 now surrounds what happened that day.

Mindy Corporon – “What happened to them could have happened to anyone.”

Faith Always Wins Foundation

The shooting was national news. “I didn’t understand for several days that it was national news or worldwide news because I was so involved in it at the heart of it,” Mindy says. People from around the world donated money and wrote letters to the Corporon family. “A lot of money came in, which was wonderful and nice, and I know people are trying to help in their own way,” Mindy says. She asked that people give to Boy Scouts of America, Operation Breakthrough, and the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection. But money kept coming in under Mindy’s name. They quickly opened a foundation: Faith Always Wins Foundation. On May 21, 2015, Reat’s birthday, the foundation officially became a charitable organization. Faith Always Wins aims to promote understanding through acts of kindness. It hosts an event called “SevenDays. Make a Ripple. Change the World.” The event is a week of commemoration and remembrance that falls on the anniversary of the shootings. Mindy’s mom came up with the idea of SevenDays because the shooting happened on Palm Sunday, the beginning of a seven-day religious observance for Christians that ends with Christ’s resurrection. A lot of people wanted Mindy and Jim LaManno to put Terri LaManno’s, Reat’s, and William’s names on the event. But Mindy and Jim both agreed that wasn’t a good idea. “What happened to them could have happened to anyone,” Mindy says. “We wanted the event to be bigger than all of them. We started the event because of them, but we wanted it to reach more people. We felt like if it had their names on it that it would really ground it. We knew that Reat, Terri and Dad wanted to make a difference with their deaths.”

For seven days each year, including the anniversary of the shooting, the foundation hosts events to promote positivity, understanding and love in the Overland Park community. The activities include community dinners, interfaith workshops, and blood drives. The week ends with the Faith, Love & Walk to encourage the community to come together to overcome evil. Mindy started the foundation in 2014, and, in February 2018, she left her position as CEO of a wealth management firm to run the foundation full-time. “I just can’t stop thinking about how it is supposed to be better and bigger,” Mindy says. “And when I say bigger, I don’t even mean nationally yet, I just want it to be better and bigger in Kansas City. I want everyone in the world to know that Kansas City won’t let evil overcome us. I wanted us to be that beacon of light.” Mindy sees Kansas City as the heart of the United States. “We haven’t had any riots. We haven’t had people clamoring. We haven’t had fires,” Mindy says. “… We haven’t had negatives that come from other cities, and I want us to keep building on that. And showing that we know how to overcome evil and stop evil in its tracks.”

The night of the shooting, Mindy heard about a student vigil happening at a local church. She felt that she needed to speak, despite her family’s concerns. When Mindy was 16, she lost a friend in a car accident. She was devastated by the loss. “It just blindsides you when a dear friend is killed somehow,” Mindy says. She didn’t want the students to feel that same way, so she went to the vigil and spoke herself. “I know life will go on,” Mindy says. “I know the sun is going to come up tomorrow. I know people are going to be really sad, and I have no idea how I am going to make it through it. But I wanted them to know that I have already experienced this once and I know what they are going to experience.” Lauren Bamber, who has lived in the Kansas City area since 2011, saw Mindy’s immediate guidance as one of the reasons the community moved forward. “The positive responses come partially from Mindy’s leadership because the community could have had anger and resentment, and I am sure there was some of that,” Lauren says. “But Mindy turned it into such a force for positive. Yes, she grieved, but also at the same time, she was determined to show that faith always wins.” Today, Lauren works as an administrator at Racial and Religious Acceptance and Cultural Equality (RRACE) Foundation, which was founded in the aftermath of the shooting. Lauren said Mindy helped her take a positive outlook on the situation, even though she tends to be a pessimist. This is exactly what Mindy wanted people to do. “I wish people knew they didn’t have to sit in the grief and feel alone,” Mindy says. “There is something to do, and there is a way to help them to move onward.”

Rabbi Mark Levin of Congregation Beth Torah in Overland Park was at home waiting to go to dinner. It was his wife’s birthday. He got a call from a close friend saying there was a shooting at the Jewish Community Center.

He arrived within the hour.

Jake Svilarich was on a bike ride with his dad when his mom got a call about the shooting. He walked into his kitchen to his mom bawling. The only word she could get out was “Reat.”

Jake immediately went to his room. He looked at news articles online and got calls from friends.

“I came home to a mess,” Jake says.

Mackenzie Haun, a senior at Blue Valley High School at the time, was at a Passover seder when she found out about the shooting.

“It changed the whole tone immediately,” Mackenzie says.

Adversity in the Aftermath

After the shooting, Rabbi Levin and others put together a committee to assist in the face of trauma. The committee decided to interview those who were directly involved with the shooting.

“One of the things that we learned through all of this is that people tend to not take care of first responders,” Rabbi Levin says. “So we have learned to watch out for the people who are directly involved.”

Rabbi Levin said that Paul Temme just happened to be on the scene of the Jewish Community Center when the shooting happened. Paul was in the parking lot when he heard gunshots. He ran after Miller’s car until Miller shot at him. Miller missed.

“This had an impact on him, and he doesn’t like to talk about it,” Rabbi Levin says.

Paul tried to help Reat, but he couldn’t. Fortunately, a former EMT worked at the theater at the Jewish Community Center. The EMT knew exactly what to do until the ambulance arrived.

“That fact was incredibly helpful because no one then had to say, ‘We could have done more,’” Rabbi Levin says. “Everything that could be done was done.”

Other people who were at the campus that day were affected. Students at Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy were quickly ushered into a room on lockdown. Kids inside the theater practicing for an upcoming production were hurried to the back of the theater.

“There were a lot of people around the campus who had direct contact one way or another that felt threatened about the fact that maybe there is more than one shooter, maybe this guy is going to come in,” Rabbi Levin says. “They were traumatized.”

Rabbi Levin also heard of people who were affected at Village Shalom, a Jewish retirement community. A friend of his had just visited her mom that morning, and she wasn’t sure if her mom died in the shooting or not. Her mom was not harmed during the shooting.

“It’s four years later, and I don’t know if she is over it to this day,” Rabbi Levins says.

#ripreat you're light will burn on forever in the hearts of those you touched around you pic.twitter.com/q0HorlBYQp

— Hannah Krieg (@hannahblitz) April 19, 2014

Thank you to the @Royals for playing Reat Underwood's rendition of the national anthem tonight. Beautiful. #RIPReat pic.twitter.com/5mSFQRniFL

— Blue Valley Softball (@BVTigerSoftball) June 8, 2014

https://twitter.com/CarolineK414/status/457375714958774273

Loved how everybody came together today #RIPReat pic.twitter.com/5weoLdHmSy

— Austin Mccarty (@mccarty_austin) April 19, 2014

Our community is absolutely amazing #RIPReat pic.twitter.com/BvDdzB6Qo0

— Emma Hardeman (@Emma_Hardeman) April 18, 2014

#RipReat #LoveWins ❤️ pic.twitter.com/6lAMNnQsBC

— rin (@erinklausss) April 18, 2014

https://twitter.com/QB_Darb/status/457249465477255168

A line that never ended. #RIPReat #LoveWins #LifeLifeToTheFullest pic.twitter.com/VOKqeibB4O

— Logan Laree (@_LilLoPeep) April 18, 2014

Mavs will be thinking of Reat & his family today! #RIPReat ❤️ pic.twitter.com/IB4E692XNY

— adeline ellis (@ellisadelinek6) April 18, 2014

https://twitter.com/angela_ryan18/status/456199440278106112

https://twitter.com/_savannahortiz_/status/456171371916038145

https://twitter.com/CarolineK414/status/456166971424256000

United Students

Students at Blue Valley High School felt the somber effects, even if they weren’t near the shooting that day.

Students at Blue Valley High School felt the somber effects, even if they weren’t near the shooting that day.

The only time Reat’s friend, Jake Svilarich, was late for his freshman biology class was the day after the shooting. He and his buddy Reat had this class together.

When he walked in, the whole class broke down in tears.

“The weeks after, everything was real quiet. It sucked,” Jake says.

Another student at the school, Mackenzie Haun, saw the same thing.

“I had never heard the school quieter than it was that day,” Mackenzie said. “Everybody was just gathered around. There were people sitting around and crying. For a school that was usually so bursting with life, it was so, so quiet. It was very unsettling.”

Eventually, things changed.

“Afterwards, it did become a big force of love.There were hearts put on every locker, there was a whole shrine to Reat on his locker,” Mackenzie says. “The community really came together, but it was a really hard transition.”

Jake relied on his friends for support.

“If it weren’t for that group of people and all of the outpouring of support from even just the people at school, and the staff, and other people I wasn’t really friends with but knew and that kind of thing, it would have been a lot harder to especially go to school,” Jake says.

Jake and his friends leaned on each other after the shooting. They went to vigils and the funeral together. They spent a lot of time on the phone.

Jake felt there was a huge turnout in the school community for all the events that were held after the shooting.

Westboro Baptist Church announced it would picket Reat Underwood and William Corporon’s funeral because they were on Jewish property when they were killed. The church is considered an anti-Semitic hate group by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

The community responded by packing the church and lining the street with counter-protesters to create an “Angel Wall.” Thousands lined the streets wearing white.

On the day of the funeral, the sanctuary was packed, and the road was lined with people outside of the church. Jake says seeing the community support helped him move forward.

“There was just so many people there at all the other events and even just the little things, just people going to talk,” Jake says. “There were always big crowds there to support whoever was speaking or whatever the event was. I think there was a whole lot of positive response to that from a faculty [and] student body standpoint. I think everybody did a really great job coming closer to support everybody that was hit by that.”

After the shooting, community members bought hundreds of wristbands that said, “Remember Reat, Romans 8:28”.

In all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose – Romans 8:28

Jake still wears his today.

Rabbi Levin saw the community unite, as well.

“The shock was how people came together,” Rabbi Levin says. “The shock was the Christian community, the Jewish community, the Muslim community, everybody saw this as having happened to them. They all came together in support.… It was phenomenal, it was absolutely phenomenal.”

Unfortunately though, the attack was intended for the Jewish community. Just six miles away from the high school, a community was transformed.

A Targeted Attack

Miller’s attack was clearly targeted at Overland Park’s Jewish community.

The Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City is a 40-acre campus, centralizing several Jewish educational, cultural and recreational agencies.

“They took all of those agencies and put them in the same place, whereas most communities that you go to have their agencies spread out,” Rabbi Levin says. “Some communities have a campus, and this community is one of them.”

Less than a mile away is Village Shalom.

“What happened was that this Nazi knew that and planned to kill Jewish people,” Rabbi Levin says. “So he went where he thought he would kill people, which is the Jewish community campus … Ironically, because they are community facilities, he killed three people who were not Jewish.”

Everyone who died at the shooting was Christian, which complicated the emotional response of a lot of people in the Jewish community.

“It was awful just because people were killed, but for Jews—I think I am speaking for more than just me—but there was also—there was a layer of guilt that none of the three people who were killed were actually Jewish,” Mackenzie says. “You felt somehow to blame for that.”

Beyond feelings like this, the community security was threatened.

Congregation Beth Torah – “Ironically, because they are community facilities, he killed three people who were not Jewish.”

Jews “went from feeling safe to feeling unsafe,” Rabbi Levin says. “It is not entirely a new feeling. Psychologically, for many people, what they had lived with and blocked for their entire lives, now became a reality.”

The security changes made throughout the community after the shooting are still seen.

“I used to be able to walk into the synagogue at any time, any day, and it wasn’t really locked and there was only security guards for special occasions,” Mackenzie says. “And afterward, it was very much the opposite. There were security guards every day, the doors are always locked. It was a huge shift. They still try to be as welcoming as possible, but it is just difficult when it is so much harder to know what happened.”

Rabbi Levin says he thinks that fear created from the shooting lasted for a long time afterwards and reverberated throughout the community.

“And not just for a few people and not just people whose family were involved, but for people who said, ‘I don’t know if I want to go where Jews are congregating,’” Rabbi Levin says.

Rabbi Levin and Mackenzie both agreed that they feel anti-Semitism is rare in Overland Park. Growing up, Mackenzie really never dealt with anti-Semitism.

“It was just very shocking because this was different than everything I was used to,” Mackenzie says. “And I mean, it really shaped a lot of how I thought about the world. It really had an impact on everything. It is definitely a big part of who I am, even though all the goodness that came from this tragedy, it was still a reminder of the people that are not so kind in the world.”

Mackenzie says the anti-Semitism is always in the back of her mind.

“I try not to think about it too much because it can overwhelm all of the very good things that are happening, but it is definitely something I am keenly aware of pretty much all the time.” Mackenzie says.

The initial investigation of the Overland Park shooting concluded that it was a hate crime. Since 2014, anti-Semitic incidents increased by 21 percent for the first time since the 1990s, according to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

Regardless of current trends, Rabbi Levin says knowing some people hate Jews is a part of Jewish identity.

“Jews grow up with the idea that you may be hunted. There is this culture that we know that people hate us. Not everybody, not a majority. But that things can turn on you like that,” Rabbi Levin says, snapping his fingers.

That’s what happened when Frazier Glenn Miller drove into the Jewish Community Center parking lot on April 13, 2014.

“Now, after saying to yourself, ‘It will never happen here for your entire lifetime,’ suddenly it happens,” Rabbi Levin says. “The idea that we might be persecuted, everybody knows that. Nobody really thinks it is going to happen, and then it happens.”

Anti-Semitic assaults weren’t a rarity in 2014. The ADL reported 36 anti-Semitic crimes, which included murders.

Anti-Semitic assaults weren’t a rarity in 2014. The ADL reported 36 anti-Semitic crimes, which included murders.

One of those was Miller’s attack.

Miller was never charged with a hate crime, although it was determined the motivation behind his crime was hate.

“We have unquestionably determined through the work of local and federal law enforcement agencies that this was a hate crime,” said John Douglass, police chief at the time, at a press conference on April 14, 2014.

Miller admitted to the Kansas City Star in an exclusive jailhouse interview that he wanted to target and kill Jews. During the arrest, Miller reportedly was heard yelling, “Heil Hitler.” He’s also a former Ku Klux Klan leader and founded a white supremacist group, according to CBS.

The shooting in Overland Park was the first time a Jewish organization had been victimized by a gunman since a 2009 shooting, according to a report by the ADL.

“This tragedy brought home to us the vulnerability of being Jewish,” Rabbi Levin says. “And it is not exactly a unique status in this country, but it is unique if it is you. It certainly feels unique.”

Last year, for the first time in seven years, the ADL recorded at least one anti-Semitic incident in all 50 states in the U.S. Anti-Semitic incidents jumped 57 percent last year, according to an ADL audit. The ADL defines these incidents as “assaults, vandalism or harassment.”

On Nov. 10, 2015, Miller was sentenced to death in the Johnson County Courthouse in Olathe, Kansas, and is on death row.

The residents of Overland Park and Kansas City could never have imagined that the hateful tragedy that played out at the Jewish Community Center and Village Shalom would ever repeat.

And then it did, three years later, in another Kansas City suburb.

On Feb. 22, 2017, a man at an Olathe, Kansas, bar yelled racial slurs at Srinivas Kuchibhotla and Alok Madasani, two men originally from India, and reportedly said, “Get out of my country!” He then shot the two men, killing Kuchibhotla and injuring Madasani.

Some reports say the man told a bartender that he had just killed two Iranians.

“The Olathe one hit really hard,” says Mindy Corporon, whose son and father were murdered in Overland Park. “It could have been stopped. At what point do we intervene?”

The shooter was found guilty in August 2015 to premeditated first-degree murder and two counts of attempted premeditated murder. This tragedy could have been prevented.

Miller wasn’t supposed to be able to get the guns he used to murder Terri LaManno, Reat Underwood, and William Corporon. He was a convicted felon and prohibited from purchasing a firearm.

The Kansas City Star reported that he and another man went to a Walmart in Republic, Missouri, four days before the shooting. Miller picked out a gun, in the presence of a Walmart employee, and when he went to buy it, claimed to have forgotten his ID. His friend then bought the gun instead.

Miller got his hands on two other guns, one at a gun store and the other at a gun show.

Two years after the shooting, the Corporon and LaManno families sued Walmart, the gun store, and the operators of a gun show where Miller bought the additional guns. The lawsuit alleged that the sellers “knew, had reason to know, or recklessly failed to know that Miller was not lawfully entitled to purchase or possess a firearm.”

After over a year in the courts, the Corporon family settled its lawsuit against Walmart for an undisclosed amount in August 2017. The LaMannos’ lawsuit is pending.

This February, Walmart announced it was raising the age to buy a firearm and ammunition from 18 to 21. The supermarket giant made the change after the February 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, where 17 people were killed.

Jim LaManno – “The man who shot Terri and the Corporons, he was just a racist, and he wanted to prove some odd point to people he didn’t even know.”

Since Reat’s death, Mindy has written letters to the parents of students killed in other shootings.

“I have 17 I have to write right now for Florida,” Mindy says. “I relate to the enormity of losing your child when you shouldn’t. I totally relate to that. And the families have no idea how long the journey is and how painful it is. It seems very, very painful at first because it is so sudden and so full of shock, but it takes a long time. It is just a really long process.”

In her letters, Mindy gives advice to mourning parents. But ultimately, she says, it takes time.

“‘Time is the only thing,’ people will say. ‘Time heals,’ and that is really not true,” she says. “Time just gets you further away from the enormity of the pain, but to heal yourself, I think you have to take time to remember your loved one.”

Even though he lost his wife that April, Jim LaManno says he knows how those parents in Parkland feel. He especially felt for a father he saw on the news.

“I saw the man who lost his daughter down in Parkland, and I know how he feels. I can see in his face. I know exactly what he is going through,” Jim says.

While Jim sees parallels between the shooting that took his wife’s life and those occurring across the country, he also feels there are major differences.

“The man who shot Terri and the Corporons, he was just a racist, and he wanted to prove some odd point to people he didn’t even know,” Jim says. “Whereas I believe some of the other shootings are just people who they are just mentally ill. We don’t have facilities or help for people like that.”

Many of the people affected by the deaths of Reat, William and Terri say they don’t necessarily have the answer to prevent hateful violence. However, that hasn’t stopped them from taking steps to move forward and making a positive impact after that terrible day in 2014.

A man cast a stone of hate into Overland Park, but the message he tried to send turned quickly to one of love. The community countered with a ripple of compassion.

Today, the legacy of Reat, Terri, and William lives on through the waves of support that started the day of the shooting.

A Ripple of Remembrance

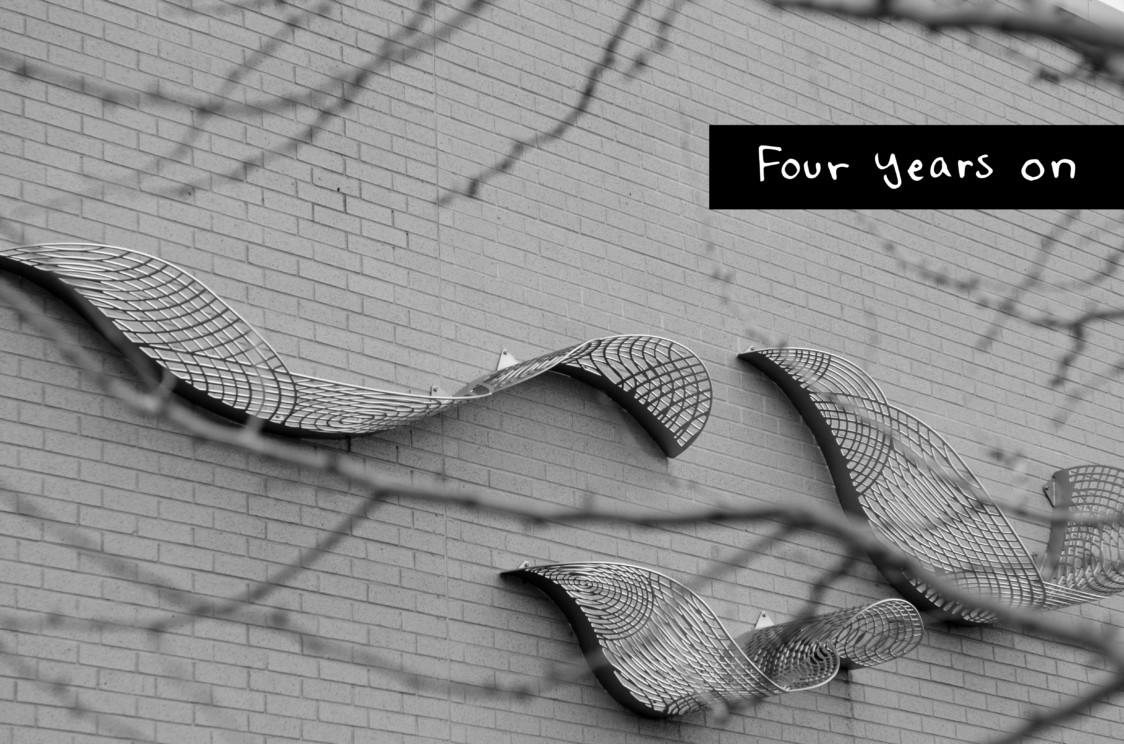

Little reminders throughout the community ask people to reflect on what was lost that Sunday. The most prominent in the community is a sculpture of three ripples mounted on the side of the theater at the Jewish Community Center. A nearby plaque is printed with pictures of Reat, William and Terri.

A bench sits in front of the high school Reat attended, facing the school. The inscription reads: “As a freshman at BVHS, Reat loved singing, debating, acting, learning and living life! He was a true friend and made this world a better place.”

The debate and drama programs offer awards in his honor. The high school offers a scholarship in his name.

The middle school that Reat attended also has a sculpture in memorial.

In the Prairiefire Wetlands in Overland Park, two trees are planted in memory of William and Reat.

Across state lines in Kansas City, Missouri, a memorial garden is planted for Terri. The garden is behind the Children Center for the Visually Impaired, the place where Terri worked.

All of these memorials serve as reminders of the positivity Reat, William, and Terri brought into the world.

“We are focusing on the victims,” says Lauren Bamber, administrator at RRACE (Racial, Religious, Acceptance and Cultural Equality). “We are going to focus on their lives, what positivity they did bring into the world and what their message would have been and what they would have wanted.”

Executive Director of Interfaith Programs, Faith Always Wins Foundation – “By opening up a conversation, we have a better opportunity to understand one another.”

A Ripple of Acceptance

Although the community looks back to remember those lost in the shooting, their legacy lives on in other ways. “One of the beautiful things I have seen in Overland Park specifically is that this community is extremely resilient, extremely proactive in wanting to address interfaith more,” says Clare Stern, executive director of interfaith programs for the Faith Always Wins Foundation. “There are proactive measures all around. And it is not just a small thing, it’s a large thing that is becoming ingrained into the DNA of the Overland Park area.” The Faith Always Wins Foundation is one of the waves of positivity that came from the shooting. The logo of the “SevenDays. Make a Ripple. Change the World.” event has seven rings. Three are left empty to remember Reat, William and Terri, but the other four are filled with color to show the spirit of positivity that continues since the shooting. Every year, the victims are remembered through seven days worth of events, but the community is also reminded to create a ripple of change in the community. On each of the seven days, the foundation hosts activities that encourage interfaith discourse while also making a difference in the community. The events range from speakers, to workshops, to blood drives. The event ends with a walk called “Faith, Love & Walk.” “The SevenDays walk has just done more good than you can possibly imagine,” Jim LaManno says. “We are very happy about that, and that is a positive thing. It is something that I look forward to. It is kind of looking to the future. … I think there are many people who look forward to our walk and who do it.” For Mackenzie Haun, the SevenDays event is an important piece of the attitude of the community. “The community has reacted in the best way it possibly could have,” Mackenzie says. “Everything with the walk and the ripple and the pins, everything has been so wonderful.”  For the first few years, the walk was held in Overland Park, but has since moved to downtown Kansas City, Missouri. “We want to be more inclusive,” Jim says. “We want to get more people involved, more people to do the walk, more people to come together as a society.… Our goal is to have a very diverse group and a group that comes together and works as a team. Because that is what we really need is people that come together.” The SevenDays event is the signature event of the Faith Always Wins Foundation. All proceeds from the event benefit the Faith Always Wins Foundation and the LaManno-Hastings Family Foundation. Another part of the Faith Always Wins Foundation is empowering people of different faiths to engage in dialogue.

For the first few years, the walk was held in Overland Park, but has since moved to downtown Kansas City, Missouri. “We want to be more inclusive,” Jim says. “We want to get more people involved, more people to do the walk, more people to come together as a society.… Our goal is to have a very diverse group and a group that comes together and works as a team. Because that is what we really need is people that come together.” The SevenDays event is the signature event of the Faith Always Wins Foundation. All proceeds from the event benefit the Faith Always Wins Foundation and the LaManno-Hastings Family Foundation. Another part of the Faith Always Wins Foundation is empowering people of different faiths to engage in dialogue.

“Our goal is to open up dialogue for most everyone who wants to be a part of an interfaith conversation,” Clare Stern says. “The more we converse with one another through civil discourse, the more we have the opportunity to break down misunderstanding and have less fear and ultimately less violence in the community. By opening up a conversation, we have a better opportunity to understand one another.” One piece of this initiative is a youth board made up of teenagers from different faiths and non-faiths, including atheism, human secularism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity and Hinduism. “When kids have the opportunity and the tools to do that, the more empowered they can become and the better leaders they will be,” Clare says. “Not only in interfaith settings, but in the workforce later on, post-college.” The Faith Always Wins Foundation also looks to honor the victims of the Overland Park shooting financially. The Faith Always Wins Foundation created a grant program to help remember Reat and William. The funds give grants in the performing arts and the medical field because Reat and his grandfather shared a love of performing arts and William was a doctor. They also give grants to organizations for grief and healing.

A Ripple of Inspiration

When Dr. Ekkehard Othmer and his wife, Sieglinde, heard about the shooting, they felt like they needed to do something.

Ekkehard says the shooting hit close to home because he was born in Germany during the rise of Hitler.

“It was one of those times that an event happened and it wasn’t just another news story and you move on,” Lauren says, an administrator at RRACE. “It was something that left a mark. For him, he needed to do something about it. And so, we founded a charity … They wanted to do something positive in light of something so heinous.”

As a RRACE initiative, the Othmers started a songwriting competition that is incorporated into the SevenDays events. The couple supported the Kansas City SuperStar competition that Reat was auditioning for the day he died.

Ekkehard was overcome with emotion that Reat didn’t sing that day. Lauren says this is what compelled him and his wife to start their nonprofit.

“For them, I think it really was about getting the message to the kids and focusing on the next generation,” Lauren says. “The kids are the future. … It should be the goal of all of us to leave behind a better world than what we came into. [Our goal is to] make sure those kids are able to live in a world where they don’t have to be afraid of someone coming for them because of their race or their religion.”

Today, kids send songs to the RRACE foundation that focus on the themes of race, religion, culture, and acceptance.

“We want kids to get ideas about … how can we educate people. How can we make the world a better place?” Lauren says. “How can we not just tolerate each other, but how can we accept and love and bring all of these ideas together?”

Mindy Corporon, Mother of Reat and Daughter of William – “The shooter killed three really, really, really great people, and what we did as family and what we continue to do is remember them by helping other people.”

A Ripple of Aspiration

Jim realized good would come from the shooting when money poured into the Children Center for the Visually Impaired.

“We have a scholarship there that will last for decades,” Jim says. “…There will be a fund that goes on for a very long time.”

The scholarship helps two children each year who have low vision.

“We feel with extra training, they can become productive members of our community,” Jim says.

Often school districts can’t afford to send kids who need vision support to the center.

“They lose kids through the cracks,” Jim says.

A scholarship fund is also set-up at St. Teresa’s Academy and St. Luke’s School of Nursing, both schools that Terri attended. There is $160,000 in that scholarship fund.

“If we make a small ripple, and I am adding to that ripple, I believe that we can have a more civilized society,” Jim says.

A Ripple of Understanding

Rabbi Mark Levin wrote an open letter to then-Attorney General Eric Holder before Holder visited the community on April 17, 2014 .

“I wrote, ‘You got to get beyond niceties because these communities don’t really know one another,’” Rabbi Levin says.

Some women read this post and immediately took it to heart. They started an organization called Strangers No More. Sharon Ritter and Nancy Brown, members of the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection, felt compelled to reach out to their Jewish friends.

They approached Judy Hellman, who helped kickstart the organization.

They coordinate educational programs with guest speakers and book discussions.

The goals of the organization, according to its Facebook page, are to “construct paths to understanding, build bridges through developing relationships, and pursue the possibility of future events and ways to unite and work together to make a difference in our own lives and in our community.”

The group is open to Jewish and Christian women.

A Ripple of the Masses

When Mindy went to the vigil the night of the shooting and when detectives knocked on Jim’s door, neither of them could have predicted the chain reaction of national attention to follow.

“I didn’t understand for several days that it was national news or worldwide news because I was so involved in it at the heart of it,” Mindy says.

The community reaction quickly became national news, and it continues to be to this day.

“It has blossomed to a movement not just here in the Midwest, but it is garnering national attention now,” Lauren says. “That takes strength, that takes commitment, that takes courage, and all of that in the face of what [Mindy] was going through, it’s mind-boggling.”

But to Mindy, that’s all just a part of what she needs to do to stop similar incidents.

“I can continue to tell the story because it needs to be told because it keeps happening,” Mindy says. “This story has to be continued to be told.”

The Overland Park community could have focused on hate and revenge after the heinous acts that Sunday afternoon four years ago, but that’s not what its people decided to do.

“The shooter killed three really, really, really great people, and what we did as family and what we continue to do is remember them by helping other people,” Mindy says. “There is something to do, and there is a way to help them to move onward.”

Urban Plains traveled back to the metropolitan area of Kansas City, Missouri to cover the SevenDays walk. Read the follow up here.