Stereotypically it’s beer, casseroles, farmers, but is there more to it?

The Midwest, like many that call it home, is a little squishy. The land of endless cropland and calorie-packed state fair food is hard to pin down. You can’t box it in by time zones, as the Midwest is situated within three of them—East, Central and Mountain. You can’t frame it politically, as Minnesota and Illinois leave a massive blue streak across the Midwest’s red neck—and we don’t talk about what’s happening in Wisconsin and Michigan because it’s not polite. And you can’t define us by accent either, since there are dozens out here, from da Chicago draw to North Dakota’s youbetcha and the general ope sorry. Even the 100th meridian line slices through the region.

So how do we define the Midwest? Most people use state lines. Beginning on the Great Plains in western Nebraska, head due east across land flatter than a pancake. You’ll hop across a few rivers, namely the Missouri and the infamous leading lady, Miss Mississippi, until you find yourself in Ohio. You do the same thing from the Ozarks in southern Missouri—basically the South, but we’ll allow it—and head straight north on I-35 until you get stopped by border patrol. This is the basic gist of the Midwest. If you want to get technical, the U.S. Census outlines all 12 states considered to make up the Midwest.

But the Census didn’t use the name “Midwest” until 1984. In fact, in 1880, the first iteration of the term “Midwest” only included Kansas and Nebraska, as they were the only organized pieces of land in that general area. The area we see now is the combination of the old Northwest Territory from 1783 and most of the Great Plains which were acquired in 1803.

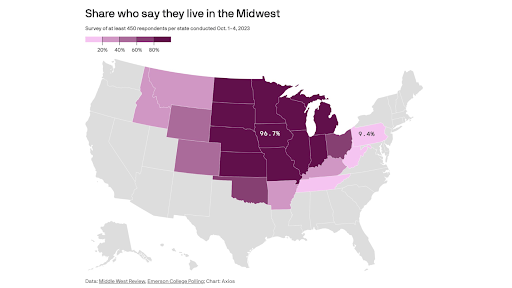

Public opinion seems to think the Midwest is even bigger than that. Based on a recent poll conducted by The Middle West Review, many people outside of the Midwest consider themselves to be living in the region. The map of respondents that claim to be Midwestern stretches as far west as Idaho, as east as Pennsylvania, and as south as Arkansas. This skews the traditional 12-state definition of the region into something more null and void.

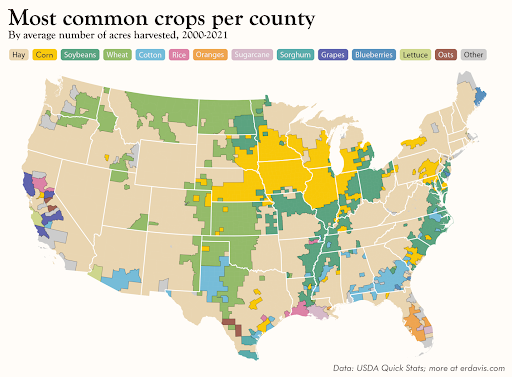

It’s time to go back to the drawing board. What if we used crop maps? Particularly corn, soybeans, and wheat—the perennial Midwestern crops. The region is the agricultural capital of the country. Surely, we can glean something from this data.

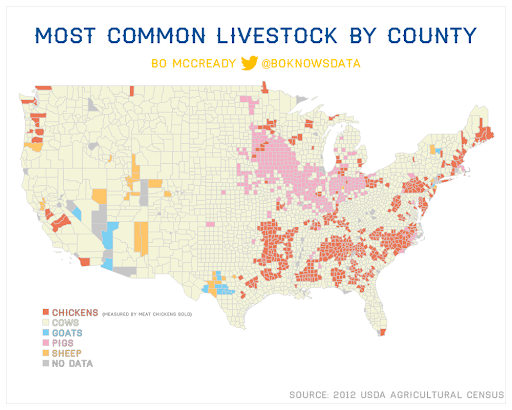

Okay, well, that didn’t help. Corn is almost confined to the region, but soybeans stretch down into the south and over to the east coast. Wheat is the same story, out sowing its wild oats all over the Great Plains and even up into the Pacific Northwest. What if we looked at a livestock map? As the agriculture capital of the country, the Midwest is no stranger to farm animals.

Yeah, not so much. Pigs are loyal to the region, but cows appear in nearly every state in the country.

We can look at U.S. maps displaying geographical region, religion, sports team allegiance, and even volunteerism, but none show us a clear image of where to draw the region’s borders. To understand the Midwest, we must recognize that the region is not definable by lines on a map.

The Midwest is not a place, it’s a people.

“And it’s an idea,” says Camden Burd, Assistant Professor of history at Eastern Illinois University. Burd focuses on environmental history, particularly that of the Midwest. “If we explore [the Midwest as an idea], then we can get a sense of the subjectivity of the Midwest. Who counts as a Midwesterner, who doesn’t count as a Midwesterner?”

As such, the Midwest has only been a region as long as people have been calling it that, about 180 years. There’s no map that shows us the glue that groups all 12 states together. There’s no map that can tell us what the idea of the Midwest is.

Burd argues that we can start to see this idea of a region through the settlement of White colonial people. These settlers moved onto the land, which had been inhabited already by Indigenous people, and declared it their own. The White settlers saw the Indigenous people as “savages,” and therefore unworthy of the land they lived on. The colonizers, considering themselves deserving, changed the entire landscape from prairie to farmland in order to suit their needs. This growth of homesteads led to the growth of market-based agriculture.

“What is really changing is that Chicago has grown into this hub of rail networks,” Burd says. “But, also for farmers in this region, it has been the central organizing principle by which they understand market exchanges of their crops.”

The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was formed in 1848 as a way to price and trade agricultural products. Farmers throughout this region look to the CBOT because their livelihood depended on it. Because of this, the relationship between rural and urban becomes intricately woven together and dependent on one another. These ties were the catalyst that molded the Midwest into what it is today and what it continues to become; the glue that holds it together.

The Midwest is a “region born of a particular historical moment and particular historical events.”

—Camden Burd, Assistant Professor of history at Eastern Illinois University

Midwestern Voices Can’t Be Silenced.

The ties that bind the cities to the country are strong and unbreakable. But they aren’t a string with cans on either end. There’s a stark cultural disconnect. As cities grow larger and spread onto rural land, the crack between them splits wider and deeper.

“For some of us who are from small towns…we’re always looking for something more,” says Katrina Phillips, Associate Professor of History at Macalester College and citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe. “Having grown up where I did…it’s much more about…the rural identity.”

Phillips embodies the small-town-to-big-city pipeline, being raised in rural northern Wisconsin and escaping to Minneapolis, Minnesota. In tandem with her Midwestern identity, Phillips has deep Indigenous roots, as is the case for many people living in the region. She expresses that a separation between the two identities would be impossible, as they have been entwined since her birth, and have continued to overlap throughout her entire life.

“How much of these components do I identify with?” Phillips says. “I don’t know where one ends and one starts.”

The Ojibwe are just one of many tribes to call the land in the Midwest home. The Indigenous community have a claim to the land, whether it is, became, or used to be their homelands. Phillips states that this is a marker of pride, proof that despite removal attempts by the government during White settlement, they’re still here because they fought back.

“Indigenous people were here before the state lines were drawn, before these regional delineations happened,” Phillips says.

Even stereotypes of Indigenous people place them almost completely in the Great Plains. Think “Cowboys and Indians” in the Wild West and the popularization of the Western film. These deeply ingrained stereotypical images have represented the Indigenous community for decades and only loosely resemble those from a singular region.

“You never see Ojibwe floral beadwork,” Phillips says. “You think about Native people in pop culture, you immediately go to the Plains.”

Not a melting pot, but a salad.

A common theme of the Midwest since its inception is the continued growth of diversity. We can see this across its history in the settlement of northern Europeans in the colder parts of the region, the Great Migration of Black people from the South into big Midwestern cities, and Latinos moving north to fill rural and urban industry labor. This growth is also apparent in the welcoming of Vietnamese refugees during and after the war, which was the tipping point in the Midwest becoming the region with the highest rates of immigration in the U.S.

Emiliano Aguilar, Assistant Professor of history at the University of Notre Dame with a focus on Latino communities in the Midwest, refers to the Midwest as a “salad.”

“At a salad bar, you can pick and choose,” Aguilar says. “We’ve picked and chose what part of these new immigrant communities we want to prioritize, what we want to welcome, and what we don’t want to welcome; what we want to resist and push back against.”

The diversity present in the Midwest is overshadowed by being “flyover country,” and the salad variety we do have is not limited to urban areas. The region is covered with small rural towns populated almost completely by people of color. One of the most prevalent minority groups in the Midwest is the Latino community.

The first of which came by way of migrant farm workers. As industry started, company towns popped up, attracting more people to come to the area and stay and settle here due to the steady employment.

“There is a connection that transcends the region through shared labor,” Aguilar says.

Just because the Latino community is overlooked does not mean they’re not an integral cog in the wheel of the Midwestern economy. And they know it. It’s why some Latino expats who have moved back to their home countries tend to still consider themselves Midwestern.

“I have an uncle born in Mexico, raised in the United States, lives in Mexico [again], celebrates the Fourth of July,” Aguilar says. “That makes him an oddball. I’m sure there’s tons of people in Mexico wondering, what the heck are you doing with those sparklers?”

Ultimately, that all means that to be Midwestern is to work hard and provide for your family. That’s the common ideal that binds all Midwesterners together, regardless of race or ethnicity. Be proud of yourself, of where you’ve come from, where you are, where you’re going, and the work that is going to get you there. If you check all those boxes, youbetcha you can call yourself Midwestern.

Great article. Fascinating facts and fun style make for a most enjoyable read.

Very nice article!

I enjoyed reading this.