Photos courtesy of Debra Yepa-Pappan, Chris Pappan, First American Art Magazine, Delina White, Rachel Cirullo, Becca Jonas, and Arianna Gastelum

Words by Arianna Gastelum

Native Americans have a history of being oppressed in the United States. With such a past, many people in the Native American communities are taking steps to keep their identities and traditions alive.

At the University of Iowa, 83 percent of students are white, whereas only 0.2 percent are Native American or Native Alaskan. In an effort to celebrate Native culture on campus, the Native American Student Association founded its annual Powwow in 1990. However, due to lack of funding and students in NASA itself, the Powwow wasn’t held from 2004 to 2008.

Today, students in NASA, like Jessica Owens and Adriana Peterson, come together every year to ensure the University of Iowa Powwow continues. “You don’t always get to share your culture with other people and also experience it,” says Owens. “So for me, it’s really, really healing to be able to have this event and be able to invite other students in on it.”

“No matter what the location of where you live [is], or the blood technicality of how much Indian you are and how Native you [are], it doesn’t matter at a Powwow because we’re all here together to just socialize and dance together.”–Adriana Peterson

Traditionally, powwows are held over the course of a few days. According to Peterson, a powwow is more than just a celebration. She says, “It’s a social gathering with non-Native and Native communities coming together to embark on change through healing–through traditional song, dance, food, music, and arts and crafts.” For Peterson, embracing and rejoicing in her Native identity is a part of healing and moving on from the issues she’s faced as someone who’s Native.

Peterson, a self-described “urban Indian,” says she never lived on a reservation or settlement growing up, so the Powwow is incredibly special. “No matter what the location of where you live [is], or the blood technicality of how much Indian you are and how Native you [are], it doesn’t matter at a Powwow because we’re all here together to just socialize and dance together.”

Dancing the Day Away

At the Powwow, one part of the ceremony starts with a prayer and the grand entry. The Flag Song and the Native American Anthem are played while Native and non-Native veterans are honored. After the introductory ceremonies, the performances move into traditional song and dance.

Elizah Pinto, one of the dancers who participated in the tradition, says that dancing is the best part of the powwow. “You lose yourself in it. It’s like a form of prayer. You just lose yourself in it and it seems like time stands still almost.” Pinto says the drummers are important for the rhythm of the dance. “Every band has their own little wavelength that they play on and I just like to dance to all of them.”

The President of the Native American Coalition of the Quad Cities, Regina Tsosie, has been attending the annual powwow since the early 90s. She says the beat of the drums is healing for the community. “It represents the heartbeat of the community. So you have the young children hear that beat, it takes them back to them being in their mother’s womb.”

“You lose yourself in it. It’s like a form of prayer. You just lose yourself in it and it seems like time stands still almost.”–Elizah Pinto

Throughout the day, there are inter-tribal dances, exhibition dances, tiny tot dances, and family specials. The drum groups play songs live for every dance, and each dance has its own significance. Likewise, each of the dancers’ patterns, beads, metals, and designs on their regalia mean something different in relation to their clan, family lineage, and overall native identity.

Family Matters

Powwows are also a way to rekindle old relationships and friendships. Tsosie, whose main clan of four is Honágháahnii from the Navajo Nation, says people identify with each other like family if they’re from the same clan. “If someone introduces themselves as Honágháahnii, then we would be related closely. Depending on their age, I would be a mother or a grandmother,” she says. “Even though they’re not blood-related, they’re clan-related.”

The highly anticipated potato dance comes after the traditional community dances. During the potato dance, pairs compete against each other on the dance arena to see who can last the longest without dropping the potato sandwiched between their foreheads. Peterson says, “You can’t drop the potato and you can’t touch it with your hands. So you just have to be awkwardly there and it’s amazing to watch and do.”

Another must-try at the Powwow is the frybread. Peterson says, “It’s a dough that’s fried on a certain type of fryer that makes it more puffy and more greasy.” Which, of course, means it’s tasty. “I like to eat frybread plain with some salt on it. But there’s a bunch of ways you can eat it,” says Owens. Joe’s Frybread offered it as an “Indian Taco,” “Indian Dog,” or just plain with salt or honey.

Like any community gathering, the University of Iowa Powwow is a chance for friends, family members, and acquaintances to come together, reconnect, and spend time with each other. It’s an opportunity for Native Americans to freely express their identities within their own community and to invite others to share in the experience as well.

Publisher of First American Art Magazine: America Meredith

Words by Andrea Beck

Photos by First American Art Magazine and Ann Sherman

America Meredith, the publisher for First American Art Magazine (FAAM), works to spotlight artists with Native heritage throughout the Western hemisphere. FAAM showcases artists from the United States, Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South America, and has subscribers throughout the world.

According to their website, the magazine’s mission is to promote and contextualize art (including visual, media, literary, and performing arts) created by Indigenous Americans, and to inspire dialogue about Native art. The magazine also serves as a bridge between the general public and the artists who create and discuss their work.

“Some artists, their ancestors may have been basket-weavers or seamstresses, and then they get into visual arts because they want to connect to their lost relatives.” –America Meredith

Meredith is part of the Cherokee Nation, and has studied art at the University of Oklahoma and the San Francisco Art Institute. Meredith describes herself as Swedish-Cherokee because while both of her parents have been heavily involved in the Cherokee Nation, both of her grandmothers are Swedish. “I’ve noticed it’s more of a trend—I see artists will describe the whole gambit, so not only their tribal affiliations but also if they’re, like, European or African or Asian or other nations,” she says. “Because I think that’s a closer attempt to get the whole picture of who we are as human beings, so I think [identity is] very fluid and complex.”

Meredith and FAAM try to spotlight a variety of artists because there is no one definition of exactly what Native art is. “People have conceptions that they know Native art, and we’re like, nobody knows Native art,” Meredith says. “It’s just always fun to expand people’s notion of what Native art is, and we definitely do try to seek out tribes that are underrepresented.”

As Meredith explains, Native art can include what people might consider classical art forms, such as painting and sculpting, but also includes beadwork, fashion design, street art, and even video games. “So if they want to make robots, if they want to do lace, it doesn’t matter the subject because what matters is who’s the maker,” Meredith says. As a general definition, Meredith says that Native art is just art that has been created by Native people. “So you can see we’re not really concerned about high art, low art,” she says. “Many Native artists are deeply concerned about reaching people who may not go to museums and who may not feel comfortable in galleries, and still finding ways to reach them even if they’re not part of the ‘art world.’”

Meredith and the other editors, staffers, and writers for FAAM are spread throughout the United States and the hemisphere as well, which helps them find and spotlight artists who may not be well-known on a national and international platform. “Oftentimes someone will be really great in a community, and no one outside that community will know who that person is. And we want to hear about those people and share them,” she says.

“Many Native artists are deeply concerned about reaching people who may not go to museums and who may not feel comfortable in galleries, and still finding ways to reach them even if they’re not part of the ‘art world.’” –America Meredith

Meredith believes that art is an important way for people to connect with their communities, and with each other. “Some artists, their ancestors may have been basket-weavers or seamstresses, and then they get into visual arts because they want to connect to their lost relatives,” Meredith says. “And then I think Native arts, you make something and then you go to the art show, or the art market, or the art fair, and that’s a way to build community and relate to other Native people, too.”

Art shows and community gatherings can be especially important for people who may not live in an area with regular gatherings. “If you live outside of really strong enclaves of Indian country, you might not have as much contact with other Native peoples as you might want,” she says. Art can help bring those who live in more isolated communities together.

“It’s just always fun to expand people’s notion of what Native art is, and we definitely do try to seek out tribes that are underrepresented.” –America Meredith

Another goal of FAAM is to make sure everyone feels welcome flipping through its pages. “I think it’s really important to be respectful and inclusive,” Meredith says. Because of this, the magazine has policies on potentially controversial topics, like the use of profanity. “I don’t want something superficial to prevent us being able to reach, you know, this young audience or different enclaves just because of some kind of silly kind of friction,” she says. FAAM is even in some middle schools, so Meredith believes it’s important for the magazine to be accessible and appropriate to all ages.

Regardless of where you live or what community you’re a part of, publications like FAAM help to bridge the gap between artists and people all across the world. Art certainly brings people together, but it helps to have platforms for discussion and discourse available to help community members engage.

Fashion Designer: Delina White

Words by Ellen Judge

Photos by Delina White

Gidakiiminaan describes the Anishinaabe connection and relationship to the land. This is a primary characteristic for the Anishinaabe identity. Anishinaabe is a Native person from the United States or Canada.

“I would identify myself as Native,” Delina White says. She incorporates her Native identity and traditions into her clothing line, I Am Anishinaabe, capturing the views and beliefs that have been passed down through generations. White’s designs show her love and appreciation for her indigenous culture and tradition. She says on her website, “The integrity of my artwork is important because it is a reminder of the Anishinaabe and Ojibwe history and its connection to my ancestors.”

White started learning beadwork from her grandmother on the Great Lakes reservation when she was 6 years old. Later, she learned how to make earrings, necklaces, moccasins and bags, traditional attire, and dance outfits, all using beading. She still uses what her grandmother taught her and the culture from her tribe to create designs. She now owns the clothing line with her two daughters, Lavender and Sage.

White started learning beadwork from her grandmother on the Great Lakes reservation when she was 6 years old. Later, she learned how to make earrings, necklaces, moccasins and bags, traditional attire, and dance outfits, all using beading. She still uses what her grandmother taught her and the culture from her tribe to create designs. She now owns the clothing line with her two daughters, Lavender and Sage.

“Colors represent the rays of the sun, the colors of flames, the color of the moon, and the moon represents our grandmother and all women.” –Delina White

The name of White’s line represents her commitment to inclusion of all Native people. She looks at the food she eats, rivers flowing into lakes, spirit beings, and animals running around to find further inspiration for her line. She says, “Colors represent the rays of the sun, the colors of flames, the color of the moon, and the moon represents our grandmother and all women.”

White uses all raw materials, like hand-tanned leather, shells, bones, coins, mirrors, and cotton and wool fabrics. White says, “Our inspiration comes from things like the weather, times we have had together, sometimes it even comes from the fabric.” Family has always been extremely important to White, so she includes her daughters, who are also artists, in her designing process. White’s daughters, Lavender and Sage, incorporate their art and designs in White’s clothing line. Both daughters find great importance in the work they are doing, especially combining traditional beadwork and textiles with their own personal styles.

“Traditional skirts have been a part of our culture since the beginning of time, and so I thought we could do our own take on the skirt so women could wear them in everyday situations…” –Delina White

White has always been interested in fashion. It has been a part of her life since she was a young girl, beading and creating with her mother and grandmother. She graduated from modeling school and received a Minnesota Arts grant for traditional art after proposing to create and display 16 traditional skirts. White says, “Traditional skirts have been a part of our culture since the beginning of time, and so I thought we could do our own take on the skirt so women could wear them in everyday situations—going to work, going to school, going to the grocery store, going to fancy events.” After that show, her business took off. She started designing and selling more clothes. Her motto is, “just do it, what do you have to lose?” She shows that in her designs; they are full of color, inspiration, and exotic prints. She creates designs that are as unique as the people who wear them.

White continues her love of design and passion for inclusion with her latest venture, a two-spirit line. Two-spirits are people who identify as both Native and a part of the LGBTQIA+ community. White’s clothing site, iamanishinaabe.com, says, “We cater to women, men, and two-spirits so they may feel strength and pride within themselves while successfully navigating throughout the many roles they perform.” She is calling the line Indigenous Resilience. White has always believed that all people are created equal and should be treated as such. She is creating this line to continue spreading Native culture and love to everyone. White is also collaborating with three other artists and is using their art to create her own fabric. She is using her bold designs to give a voice to those who might not be able to use their own. She wants to bring further light to Native causes and the issues that still surround their community. White says her line is “all about the water protectors, the North Dakota Access Pipeline fighters, the murdered, the missing indigenous women, two-spirits, and all the struggles that Native people are experiencing.” She is using culture, the artists, and even protesters’ signs to create her new fabric designs, all to be shown at an indigenous fashion show in Toronto.

White continues her love of design and passion for inclusion with her latest venture, a two-spirit line. Two-spirits are people who identify as both Native and a part of the LGBTQIA+ community. White’s clothing site, iamanishinaabe.com, says, “We cater to women, men, and two-spirits so they may feel strength and pride within themselves while successfully navigating throughout the many roles they perform.” She is calling the line Indigenous Resilience. White has always believed that all people are created equal and should be treated as such. She is creating this line to continue spreading Native culture and love to everyone. White is also collaborating with three other artists and is using their art to create her own fabric. She is using her bold designs to give a voice to those who might not be able to use their own. She wants to bring further light to Native causes and the issues that still surround their community. White says her line is “all about the water protectors, the North Dakota Access Pipeline fighters, the murdered, the missing indigenous women, two-spirits, and all the struggles that Native people are experiencing.” She is using culture, the artists, and even protesters’ signs to create her new fabric designs, all to be shown at an indigenous fashion show in Toronto.

In the future, White wants to continue to teach her granddaughter, Snowy, the history of their tribe and reservation, and the traditions of bead-making and sewing, just like her grandmother did for her. Growing up on the reservation and raising her family there has kept White close to her Native identity. It is important for her to represent that identity and history in the clothes that she makes. She tells stories with her designs; stories of her past, present, and future. She wants to broaden her clothing line to reach further and inspire more people by using her Native identify as a compass for her designs.

Self-Taught Bead Worker: Katrina Mitten

Words by Andrea Beck

Photos by Rachel Cirullo

Katrina Mitten, a member of the Miami tribe of Oklahoma, is based in Indiana and has been creating beadwork art for 45 years. Mitten has gained recognition across the country for her work, and has won multiple awards for innovation and outstanding artistry.

Katrina Mitten, a member of the Miami tribe of Oklahoma, is based in Indiana and has been creating beadwork art for 45 years. Mitten has gained recognition across the country for her work, and has won multiple awards for innovation and outstanding artistry.

The Miami tribe was based in Ohio and Indiana in the 1700s and 1800s, but was pushed out of Ohio in 1818. In the 1850s, many of the Miami people in Indiana were forcibly removed from their homes and required to relocate to Oklahoma. Mitten’s ancestors were from one of five families who were allowed to stay in the area. Because of this, when she wanted to learn beadwork, there was no one left to teach her. Mitten says she taught herself beadwork when she was 12 years old by studying the work of other past bead workers. “I felt I was born an artist—I feel like everyone is born an artist, but you need to find your medium or your outlet, how you’re going to express that artistic vision you have,” she says. “And when I was a young girl I decided I wanted to learn something that was traditional to my people, so looking around I didn’t have anyone in my area that was doing beadwork.”

[blockquote align=”none” author=””]“I was about 12 years old when I started teaching myself and I made my first loom out of a broom handle and a couple of pieces of 2×4 that were laying in the yard and some nails, and I did a very stereotypical Native design.” –Katrina Mitten[/blockquote] Mitten’s mother was a basket-weaver, but Mitten knew basketry wasn’t for her, so she began looking for another way to express herself. She was interested in trying beadwork, but couldn’t find a teacher. “Many of the arts from my people here in Indiana at that time were suppressed. There weren’t people practicing things that would identify you as a Native person after removal because we were trying to assimilate for survival,” Mitten says. “So you would try not to speak your language, you know, around non-Native people, or they changed the style of clothing they wore to fit in, to not draw attention to who they were. So a lot of things that were damaged were our arts especially. Because if you’re doing traditional art, that would identify you also as a Native person who they really didn’t want left in this area.”

Mitten’s mother was a basket-weaver, but Mitten knew basketry wasn’t for her, so she began looking for another way to express herself. She was interested in trying beadwork, but couldn’t find a teacher. “Many of the arts from my people here in Indiana at that time were suppressed. There weren’t people practicing things that would identify you as a Native person after removal because we were trying to assimilate for survival,” Mitten says. “So you would try not to speak your language, you know, around non-Native people, or they changed the style of clothing they wore to fit in, to not draw attention to who they were. So a lot of things that were damaged were our arts especially. Because if you’re doing traditional art, that would identify you also as a Native person who they really didn’t want left in this area.”

Because of this, Mitten had to teach herself. She began studying beadwork pieces that her family owned to learn the colors and designs, and was able to figure out how the stitches were done. Though Mitten later changed her style, she began with loom work, which is more like weaving than sewing. “So I’m a self-taught beadwork artist, but I started with loom work, which I really despise doing. I just do not like loom work, it’s just different,” she says. “I was about 12 years old when I started teaching myself and I made my first loom out of a broom handle and a couple of pieces of 2×4 that were laying in the yard and some nails, and I did a very stereotypical Native design.”

Naturally, as Mitten practiced and learned more, her style changed, and she began using an embroidery stitch. “But as time went on, I did more looking at our actual pieces and pieces that were left behind, so I consider those my teachers. Those artists, those bead workers in the past who left their art, those are the ones who taught me. So my art evolved from there, thank goodness,” she says.

“I felt I was born an artist—I feel like everyone is born an artist, but you need to find your medium or your outlet, how you’re going to express that artistic vision you have.” –Katrina Mitten

Now that she’s been creating art for 45 years, inspiration is a huge part of Mitten’s artistic process. Though the amount of time she spends working on a piece partly depends on the size and intricacy of the work, she says that the main part of the process is finding her inspiration and working out in her mind how to get to the final product she envisions. “I usually am in my workroom and really seriously work on the piece until it’s done. I get very focused once I start working on a piece,” Mitten says. “But I’m working on the piece constantly because I’m figuring in my mind, I’m thinking about it, how it will work, and that’s the main part with me is the planning of the piece. Once I get that first inspiration, then in my mind I’m working out how I’m going to end up in that final place with it.”

Now that she’s been creating art for 45 years, inspiration is a huge part of Mitten’s artistic process. Though the amount of time she spends working on a piece partly depends on the size and intricacy of the work, she says that the main part of the process is finding her inspiration and working out in her mind how to get to the final product she envisions. “I usually am in my workroom and really seriously work on the piece until it’s done. I get very focused once I start working on a piece,” Mitten says. “But I’m working on the piece constantly because I’m figuring in my mind, I’m thinking about it, how it will work, and that’s the main part with me is the planning of the piece. Once I get that first inspiration, then in my mind I’m working out how I’m going to end up in that final place with it.”

Family is usually a big inspiration for Mitten in her work. She’s created pieces for her grandchildren before, and also incorporated family heirlooms into her work. For example, the birth of one of her granddaughters inspired a child’s mobile that later won her an award for innovation. Another piece she worked on was a doll buggy that used to belong to her mother. Mitten herself played with the buggy as a child, and now her granddaughter has also played with it. “So it has special memories for me, and then the fact that it was my mother’s, so I call that piece “Generations,” because now my granddaughter has pushed it, and so I redid it,” she says. “Like I said, the only thing that’s original is the frame, so I had to redo the wheels, and I had to redo all the fabric, and I did the beading. And I used butterflies on the hood with butterflies being a symbol of renewal and continuance, so that that piece continues on.”

Like much of Native art, Mitten’s work has evolved over time. Even as beadwork is traditional for her ancestors, Mitten’s innovations and style have helped and evolved the medium while staying true to her roots.

Contemporary Artists: Chris Pappan and Debra Yepa-Pappan

Words by Arianna Gastelum

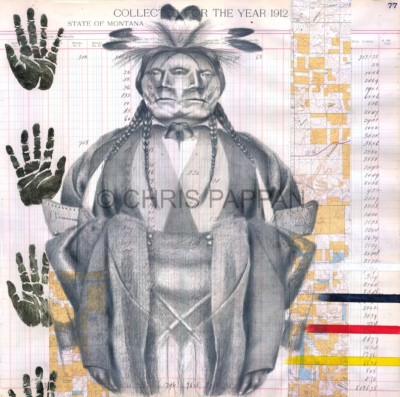

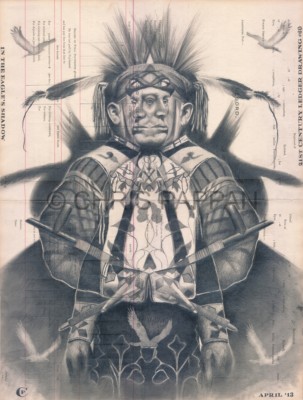

Photos by Chris Pappan and Debra Yepa-Pappan

Take down and question Native stereotypes. This is the mission of Chris Pappan and Debra Yepa-Pappan as contemporary artists.

Currently living in Chicago, Illinois, Pappan and Yepa-Pappan have dealt with preconceived notions of what being a Native person means their whole lives. Whether the topic be location, physical appearance, or the ways Native artists are expected to express themselves, the couple uses art to initiate conversations on these subjects and what it means to be a person of Native heritage.

Pappan, who is of Kaw, Osage, and Cheyenne River Siouxheritage, says his art helps to educate others about Native culture. “It’s a lot of personal searching, but then it turns into education for people as well,” he says. “When I tell people my tribe, which is where the state of Kansas gets its name from, people are like ‘Oh, I never knew that.’”

Focusing on ledger art, Pappan often combines old historical portraits of Native people with urban maps and ledger paper. “The basis of my work is the tradition of ledger art, and ledger art is a mostly Plains Native American tradition,” he says.

“When I include things like contemporary maps… it’s talking about our people’s relation to the land and how the indigenous people of these lands are still here.” –Chris Pappan

When the U.S. was expanding towards the West in the mid-1800s, ledger art became popular among Native Americans. “And then as people were forced onto reservations and into prison camps, these artworks on the ledger paper then became a visual recording of the way of life that was being taken from us,” says Pappan.

Incorporating urban maps and urban imagery into the ledger art has been a way for him to declare Native Americans are “still here” and a part of modern society. He says, “When I include things like contemporary maps… it’s talking about our people’s relation to the land and how the indigenous people of these lands are still here.”

Living Contemporary

The Pappans consider themselves “urban Indians,” meaning neither of them were raised on a reservation or settlement. There’s a common stereotype that Native Americans exclusively live on reservations, so it’s important for Pappan and Yepa-Pappan to show that this is a misconception. Yepa-Pappan, who is half Korean half Jemez-Pueblo, says, “I grew up in Chicago. I’ve lived here my entire life, ever since I was a child. So Chicago is part of who I am as a Native person who lives in the city but also as [just] a person who lives in the city.”

Using digital media is a way for the couple to criticize the preconceived notion that Native American artists can’t be contemporary or modern. “There are traditional artists that do contemporary type of work,” Yepa-Pappan says. “But that’s not what we all do. We’re not all basket weavers or potters. Chris and I, we don’t take part in any traditional craft or art form.”

Both Pappan and Yepa-Pappan often use digital media. “A lot of times I’m looking at facial features, what they were wearing in these old historical portraits,” says Pappan. “And then what I’ll do is I’ll take that photo in Photoshop as well and I’ll play around with it. I’ll try different distortions, or duplicate the image.” After finishing his desired image, Pappan then transfers it onto ledger paper and renders it in graphite. Pieces like Red Owl and Eagle’s Shadow are a result of this process.

“We’re not all basket weavers or potters. Chris and I, we don’t take part in any traditional craft or art form.” –Debra Yepa-Pappan

Unlike Pappan, who incorporates more graphite and drawings into his pieces, Yepa-Pappan uses collage art and digital media. She says, “Once I discovered digital imaging, that just became an easier means of creating. With digital imaging, I have the ability to use color and I found that I like using bright, vivid colors.”

Spock Was a Half-Breed

Two of Yepa-Pappan’s most popular pieces are Hello Kitty Tipi and Live Long and Prosper (Spock Was a Half-Breed), which were created in 2007 and 2008. In Hello Kitty Tipi, she put the Hello Kitty logo on a tipi to address the stereotype that Native Americans only live in tipis. “People don’t realize, with 500 plus tribes, we’re all so very diverse,” she says. “We live in different ways, we have different types of ceremonies, [and] we dress differently. So that was what that was addressing with that piece.”

In Live Long and Prosper (Spock Was a Half-Breed), Yepa-Pappan took Hello Kitty Tipi and made it Star Trek-themed. In the series, Spock deals with being of mixed heritage, so Yepa-Pappan used him as both a point of relatability and a way to highlight being mixed-race herself. “I kind of wanted to relate to one of the most iconic figures, which was Spock.”

“With digital imaging, I have the ability to use color and I found that I like using bright, vivid colors.”–Debra Yepa-Pappan

She also used the theme of Star Trek to address Native American culture moving into the future. “The piece itself is very much about the past because of the images that are from the past. Then it’s very much about the present in addressing mixed-race identity,” she says. “But then it’s also about the future in both the title and the futuristic element of the spacecraft and seeing ourselves as Native people in the future.”

Family Roots

Although both Pappan and Yepa-Pappan tackle Native stereotypes through varied mediums, ultimately what inevitably comes out in their works is the theme of family. In the last six years, much of Yepa-Pappan’s work has been focused on their daughter and her involvement in traditional ceremonies. She says, “It’s always hopeful when youth take part in ceremonies because you know that they will carry it through. So for me, that’s why she’s the focus for many of the art pieces that I make right now.”

Pappan, on the other hand, uses family to highlight the past and learn about himself and where he comes from. He says, “How Debra focuses on our family in the future; my focus is a bit more on family of the past and our ancestors.” For Pappan, it’s important to know where they come from. He says, “Through my work, I try to honor our ancestors more and realize that they kind of watch over us.”

Contemporary Artist & Jeweler: Jodi Webster

Video by Becca Jonas