Trigger warning: suicide

While Professor Philippe Buhlmann was in high school, his business teacher committed suicide over Christmas break. When he was in undergraduate chemistry studies in Europe, his biology and organic chemistry professor walked out in the middle of a session and never came back. Major depression, they heard. Somewhat institutionalized, they heard. When he started a desk job as a Ph.D. student, someone told him that the desk he was sitting at used to be another student’s, but he committed suicide.

Buhlmann never really stopped to contemplate these instances where mental health presented itself in alarming ways. For him, it was part of daily life. “(It) disappeared in all the other things that keep people busy,” says Buhlmann, the director of graduate studies in chemistry at University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. “When I became an assistant professor and (then) an associate professor, I realized this was not a rare thing. It hinders the progress and makes life miserable for a substantial number of people.”

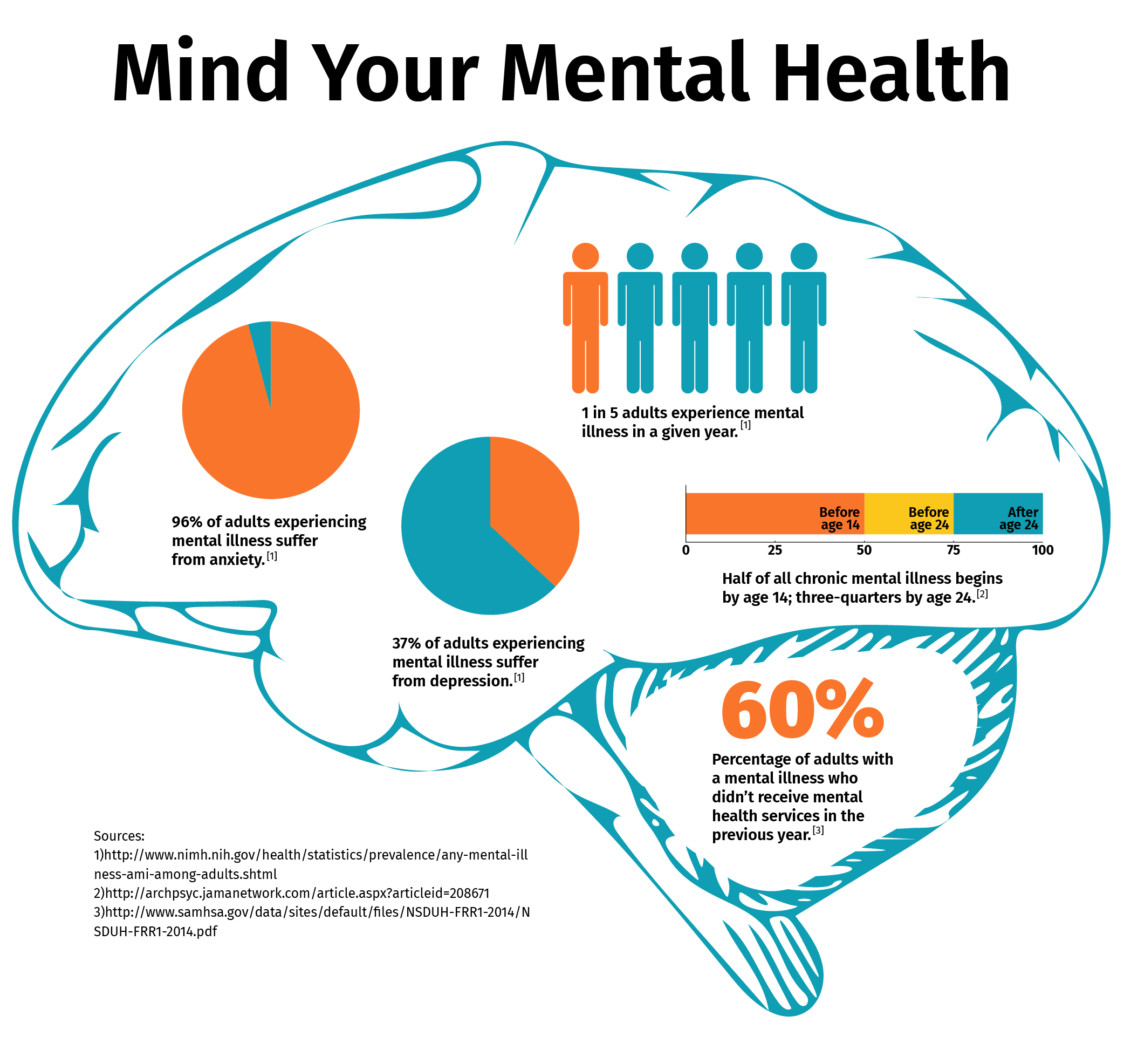

He’s right — the numbers are alarming. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), one in five adults — equalling 43.8 million people in the U.S. — experience mental illness in any given year. Of those, 16 million suffer from depression, and 42 million suffer from anxiety. Many suffer from both.

Over half of the chronic mental illnesses reported are diagnosed before a child turns 14. This means high schools and colleges are on the front lines of mental health in America, and teachers, counselors, and administrators are the the first responders of mental illness.

And while parents and policy makers are pushing for better coverage and additional resources at a legislative level, the education system is taking it upon itself to recognize signs of struggle and make the classroom culture and counseling options more comfortable for everyone.

“It’s the poor stepchild in the healthcare system.”

Mental health is a game of catch-up. While the conversation around mental illness has changed, bringing it out of the shadows and making it more accepting, the infrastructure to actually help people get better is lagging behind.

Take Iowa for example. It has a chronic shortage of psychiatrists. “121 psychiatrists in the entire state to serve 135,000 chronically and mentally ill Iowans,” says Peggy Huppert, the executive director for NAMI Iowa.

Huppert says a large part of the problem lies in the fact that the psychiatry field is undesirable to doctors — they have to be on call 24/7 and are the lowest paid field in the medical industry.

“It’s the poor stepchild in the healthcare system,” Huppert says, “so the stigma around mental health extends to the health system.”

And on top of that, mental health is historically underfunded by the government. People recognize over and over that it’s a problem — seen by the increased call for legislation supporting increased investment in mental health services after any mass shooting — but there never seems to be enough money in the budget.

Iowa has an average wait period of three to four months to see a psychiatrist, regardless of insurance type. In rural parts of the state, it can be up to six. “In what other area of healthcare would that be acceptable?” Huppert asks.

And these lack of resources have had severe consequences. A 2016 report by the Center of Disease Control and Prevention cited that Iowa’s suicide rates have increased by 36.2 percent since 1999. In 2017, there were 433 cases of suicide in Iowa.

One of those deaths was Sergei Neubauer, who took his own life in September 2017. He struggled for 18 years with diagnosed anxiety, depression, PTSD, and childhood trauma. He was adopted from Russia in 2009 at age 10 and spent years working with his parents, school counselors, and family therapists to overcome his illness and his past.

“We moved heaven and earth trying to help him,” says Mary Neubauer, his mom.

Sergei and his dad, Larry Loss, smile for the camera before Sergei’s senior prom in April 2017. Photo courtesy of Mary Neubauer

Neubauer and her husband Larry were frantic as their son’s condition worsened and they couldn’t find adequate help in Iowa. “In any other medical situation, you’re immediately referred to someone. In our case, we would turn to the professionals who are working with Sergei when he was hospitalized on an emergency basis, and we would say, ‘Where can we go? He obviously needs more help than has been provided to him so far. Where can we go? Where can he go?’” Neubauer says. “And the people wanted to help, but most of the time they just didn’t know what to tell us because there are so few facilities and so few programs here in Iowa.”

Residential treatment centers aren’t available in Iowa, so Sergei spent time completing a 30-day program with professionals in Arizona — something not every family can make happen.

“That was another hardship for us as a family, because (we’re) trying to maintain that relationship and make sure that he knows that we care about him and that were backing him and doing everything we can do,” Neubauer says, “but we’re half the country away.”

While Neubauer and her husband searched and searched for adequate help, they fell back on the efforts of his counselors and teachers at his high school in Urbandale, Iowa, a suburb just outside of Des Moines, who provided for him when seemingly no one else could.

“There was a need for students to be able to know that someone was listening.”

Sergei had a strong relationship with his counselors, which was successful, in part, because they had proper training in trauma-induced care.

“They had an open door policy for him that if he was ever feeling overwhelmed, he could go to the counselor’s office and talk with them,” Neubauer says. The principal was their next-door neighbor, and he was very active in Sergei’s mental health, telling the family they could call anytime, day or night.

But training in trauma-induced care is not a requirement for educators. Their job is to recognize signs of mental illness and send those students to the appropriate counseling centers.

That alone is a lot of responsibility, though.

Children are spending anywhere from 900 to 1,000 hours learning from their teachers every year. There’s a obligation there to understand what mental illness looks like and not ostracise those students — whether they’re forward about their illness or not.

The worst thing teachers can do is peg students struggling with mental health as troublemakers, or as lazy students pulling a fast one to get ahead. But, it happens more often than educators like to admit. Ryan Williamson, a counselor at Des Moines, Iowa’s, Roosevelt High School sees this often with students who suffer from anxiety.

“The hard part is that it is typically not tangible,” he says. “Unless the student is having a panic attack, you can’t visibly see when the student is struggling with anxiety. They display anxiety by avoidance.”

So the first step in being an advocate for students is being willing to share personal stories with them; it shows empathy and willingness to listen.

“When I started actually talking to students about (mental health) on the first day of class, saying, ‘This is something I care about, and if you are struggling with anything, feel free to come and talk,’ they did,” says Sue Wick, a professor in the biology department at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “It just became really clear that there was a need for students to be able to know that someone was listening.”

These signs are hung on professor and faculty’s doors to signify their role to students. Graphic courtesy of the University of Minnesota

Chemistry professor Buhlmann is a Mental Health Advocate. Over 50 University of Minnesota professors now claim this title and are dispersed throughout a variety of departments.

The program stemmed from the Provost’s Council for Student Mental Health, which leads campus-wide mental health initiatives. The faculty members who are a part of that council present seminars to other departments around the university on signs of mental health, and proper ways to react and respond.

Faculty involved in the Mental Health Advocacy program are trained by counselors and psychiatrists at Boynton Health Clinic on campus. After completing the program, they are given signs for their office doors signifying their title so students can seek them out if they need someone to talk to about any mental health topic.

Buhlmann says it’s incredibly important that some universal training in mental health be required for all teachers — especially those in higher education who aren’t necessarily taught the communication skills needed to deal with mental health issues during their schooling. “The majority of our professors in the United States have a Ph.D. in the field of their topics,” Buhlmann says, “(and) no training in actual teaching.”

To directly address this, schools and organizations are introducing programs to teach empathy and share resources regarding mental health warning signs. Programs such as NAMI Iowa’s End the Silence, which provides a mixed panel of young people and parents who share personal mental health stories and spark discussion; or the “The 4 R’s” training program at the University of Minnesota, a collaborative, case study-based program teaching assistants can take to learn their role in response to mental health.

But they’re not required. So the information may not be reaching the teachers who would most benefit from their lessons.

When it comes to teaching, working with student’s mental health means being flexible. Examples can include changing up exam times, allowing for makeup work to be turned in, offering testing alternatives, and being empathetic of a student’s situation, Wick says.

“It’s complicated,” she says, “but it’s not impossible. And mostly what I hear is that instructors and departments just don’t want to bother to even talk about the options.”

So the ones who do care are doing something about it.

“Kids are dying because they don’t have the services they need.”

The Children’s System State Board, developed by Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds in April 2018, completed a lengthy report in November detailing legislative efforts needed to combat the increasing numbers of children struggling with mental health. The board is made up of medical professionals working to improve children’s mental health and places heavy emphasis on the education system.

Many of their suggestions are in sync with national organizations like the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Both have suggested the implementation of universal mental health screenings, similar to hearing or dental screenings in place currently. The report also calls for increased emergency services — access centers, assertive action teams, and phone lines for times of crisis — and community-based flexible supports which allow the child to be with their family though every step of the fight.

Neubauer is the parent advocate for the Children’s System State Board and has happily filled that position knowing she is the real-world voice for so many people struggling with mental illness in their families. Much of the plan was validated by Neubauer, who expressed how much help these services would have been in Sergei’s fight.

“Kids are suffering. Kids are dying because we don’t have the services that families need here in Iowa. And that’s not an overstatement,” Neubauer says. “My family’s story shows that.”

Sergei and his mom, Mary Neubauer, try to get the family dogs to sit still for a picture before one of his Urbandale youth football games in September 2010. Photo courtesy of Mary Neubauer

It was these suffering kids that prompted Buhlmann to invest his time in stress and mental health research.

Six years after accepting his graduate studies position, a student group, the Community of Chemistry Graduate Students, partnered with University of Minnesota professors and conducted a study to be published in the December 2018 Journal of Chemical Education regarding stress and mental illness at the graduate level.

The study cites the Mental Health Survey, given on school’s campus every two to three years. In the 2016 survey, 40 percent of graduate students said they didn’t go see a therapist or counselor, even though the believed their health was suffering due to stress.

The recommendations of the study revolve around student empowerment — how holding or attending social events can lessen feelings of isolation and how the chemistry department has made program modifications based off the study — namely introducing feedback from professors and research advisors, which can lessen unwanted stress.

“It’s really a question of, ‘What can we do to create an environment where unnecessary stress and causes that lead to mental health issues can be eliminated,’” Buhlmann says. “We don’t want to lower the bars for our students … but we want our students to …. not be distracted by unnecessary hoops or through an environment that’s not conducive to them working hard and performing well.”

Again that communication component is stressed: “Our job is to provide students with feedback at a time when usually the system would not give them feedback,” Buhlmann says. He suggests something as simple as saying “good job” to students, even though stellar grades speak for themselves.

These studies and plans are an extension of the education system — they are tangible representations of the myriad issues present in classrooms and on campuses. Families and educators need to know this is being taken seriously at the highest level possible.

“I am so, so afraid, however, that we have done all this work, and we have produced this report, and it will go nowhere. I hope that’s not the case, but that has been the case with every other board that has come before us,” Neubauer says. “I am doing everything I can to make sure that people know that this is important and that we can’t afford, we truly can’t afford, to let this opportunity pass by the Governor.”

If you or someone you know needs help, please reach out to one of the following resources:

Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

The Crisis Text Line: 741741

Anxiety and Depression Alliance of America: 240-485-1001