“Climate change” is a lazy umbrella term. Yeah, the climate is changing. We know.

But the term neglects to specify the extensive array of changes scientists expect to befall the Midwest in the next few decades: rising minimum temperatures, unpredictable and intensified precipitation, less control over pest and weed cycles, evolution of crop resilience, erosion of topsoil…The list goes on.

These alterations to the Corn Belt are highly layered and very complicated. To make these developments easier to comprehend, Urban Plains assembled the expertise of three Midwestern climate scientists and the illustrations necessary to visualize the influence of climate change on the corn industry.

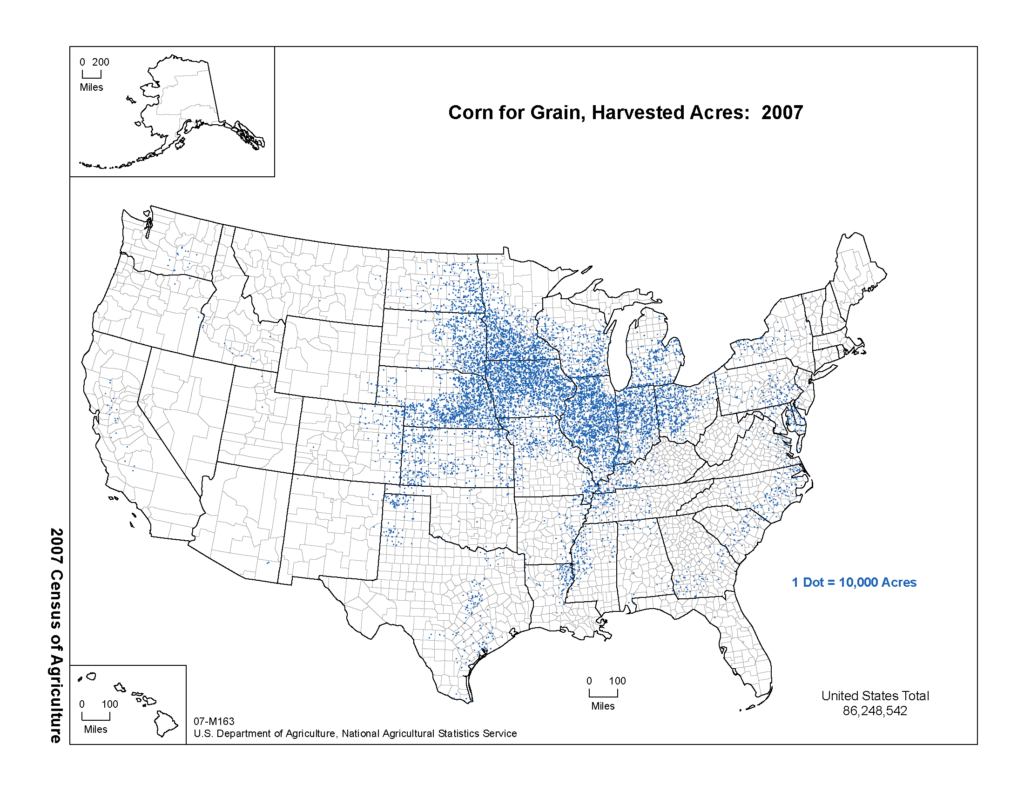

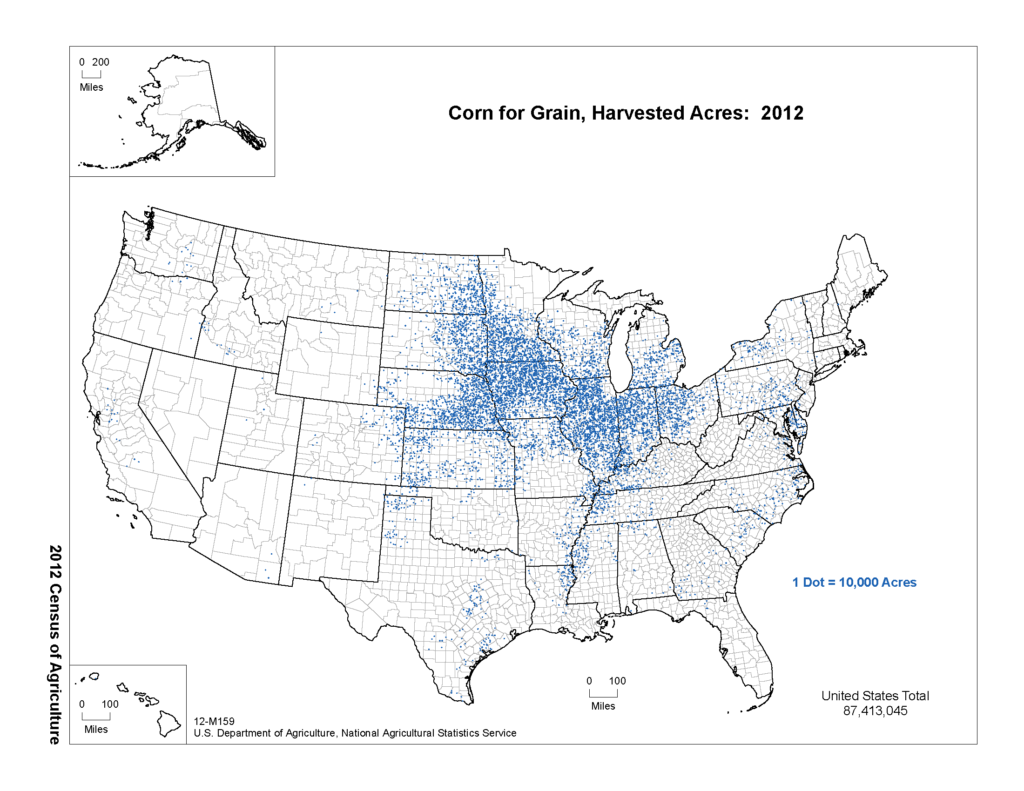

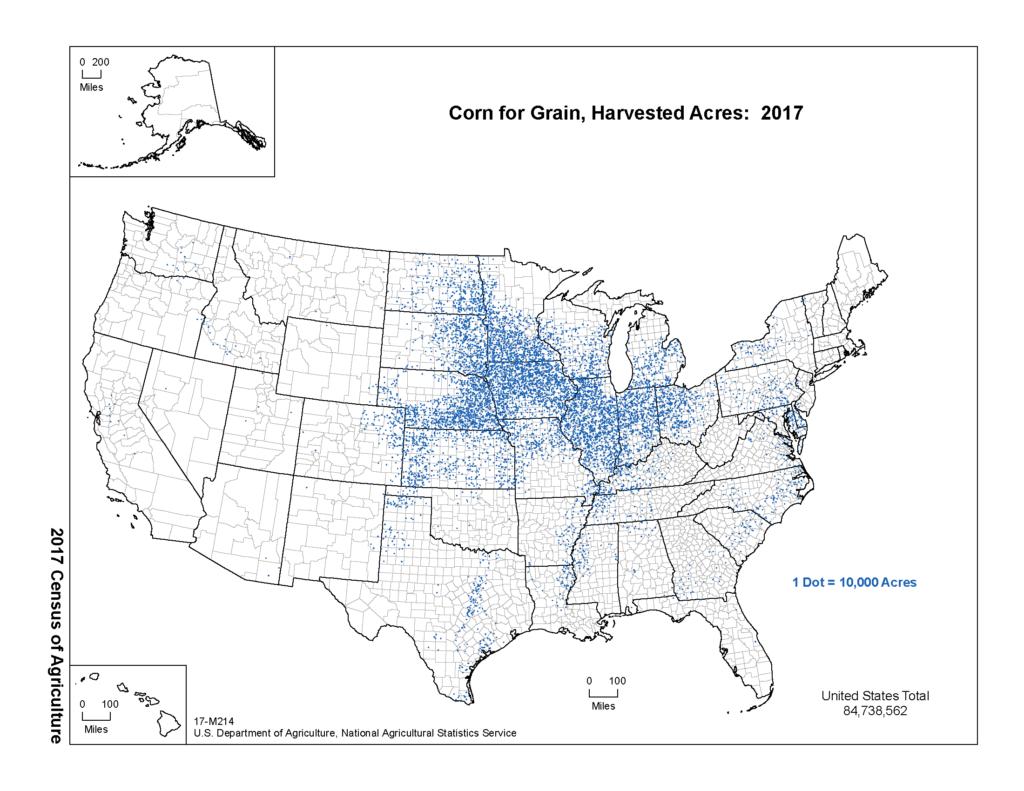

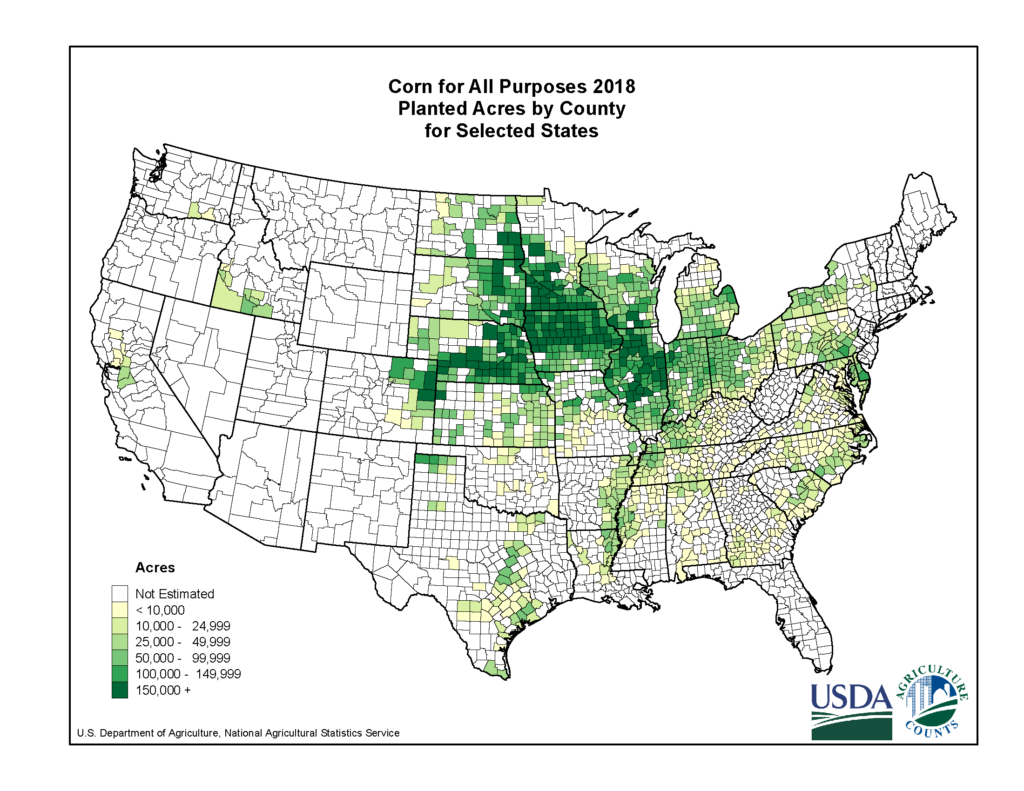

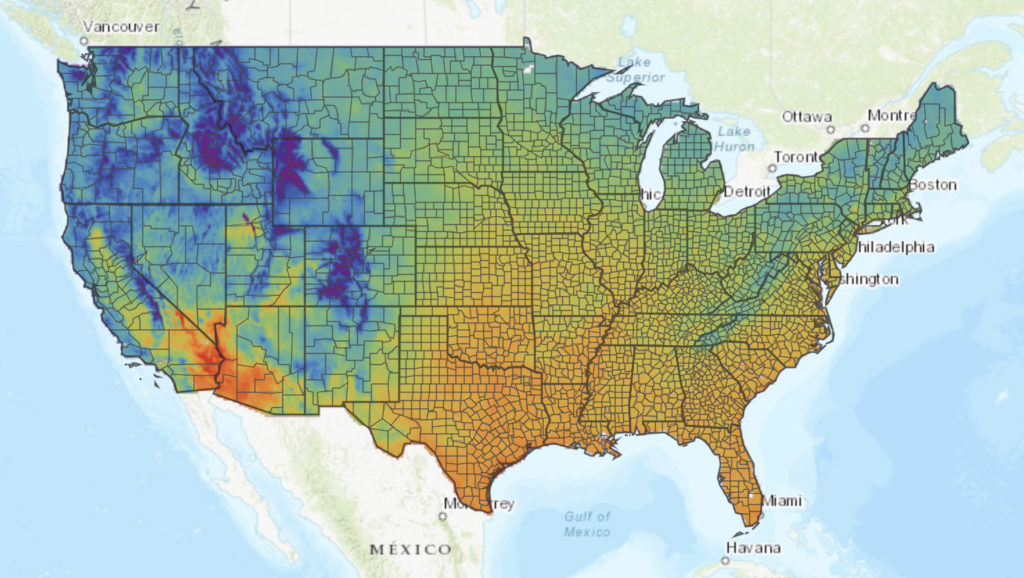

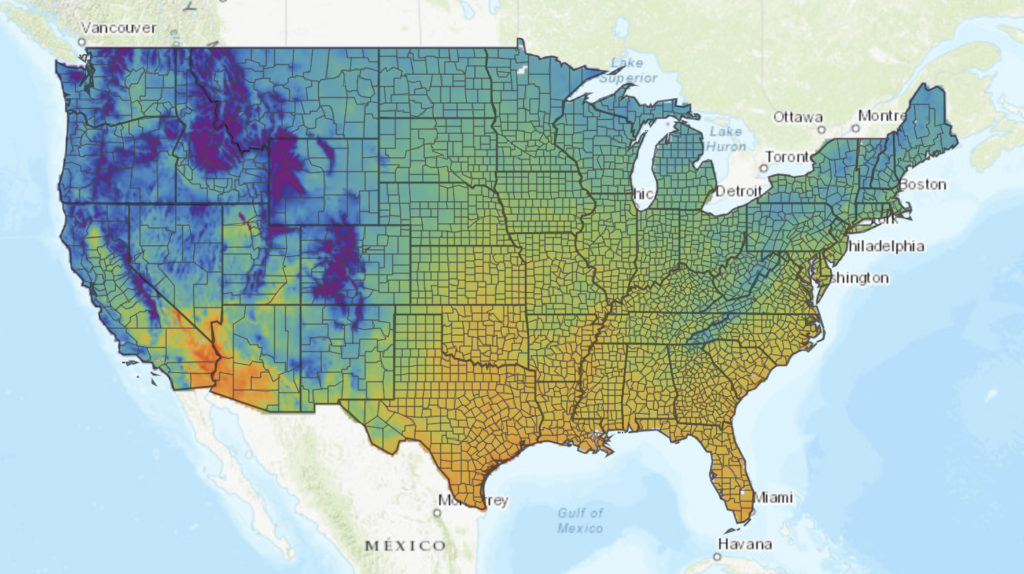

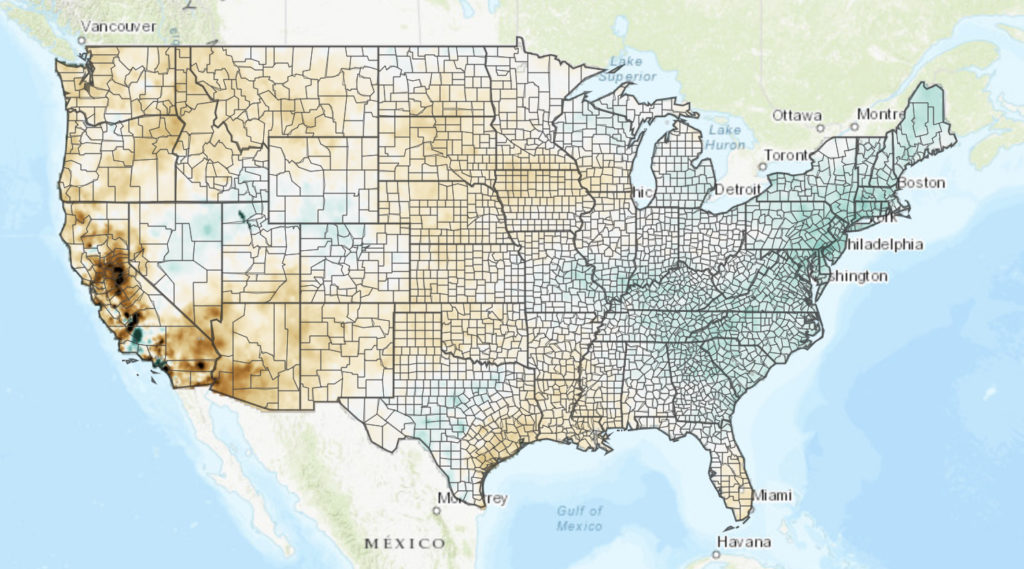

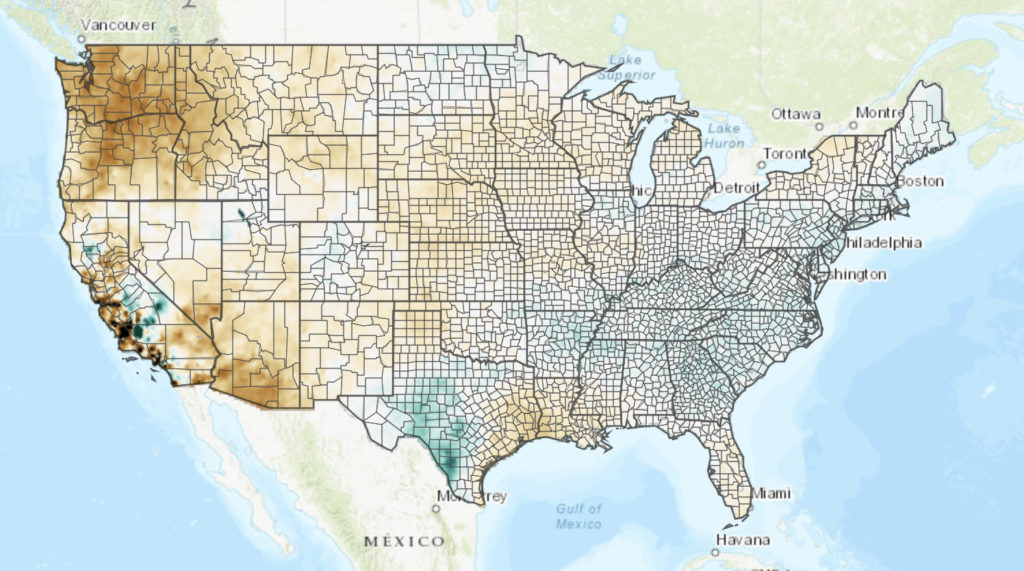

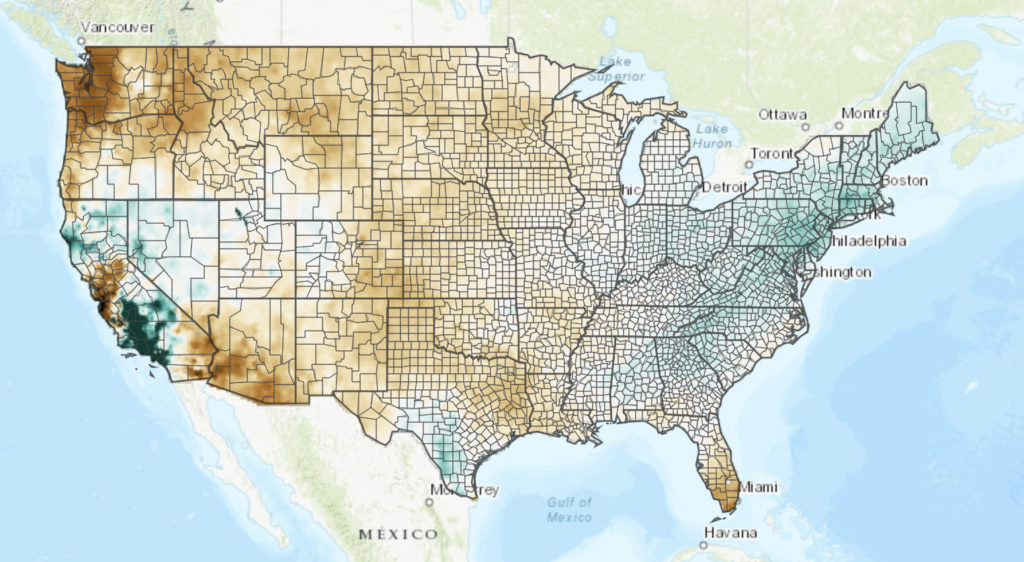

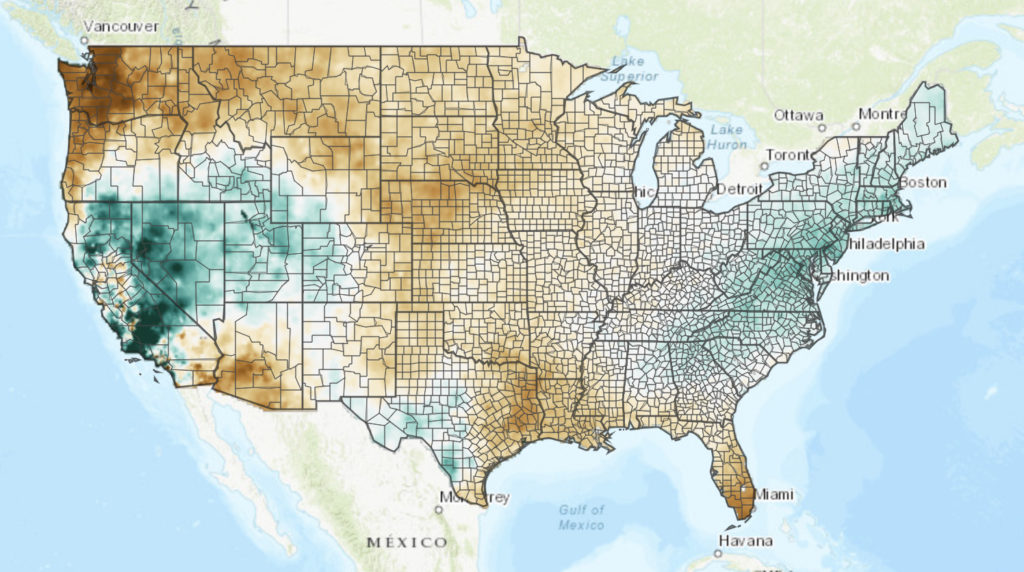

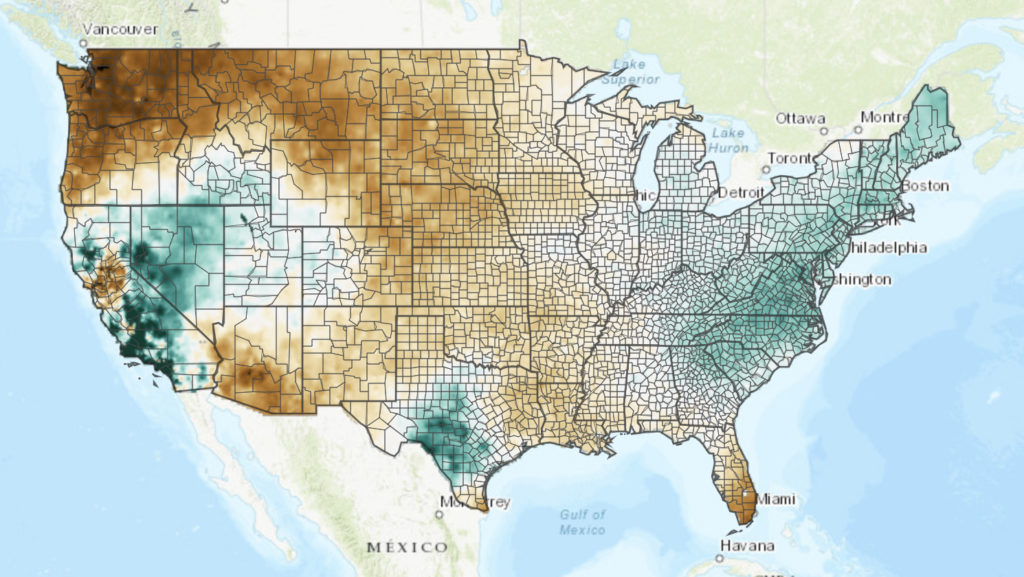

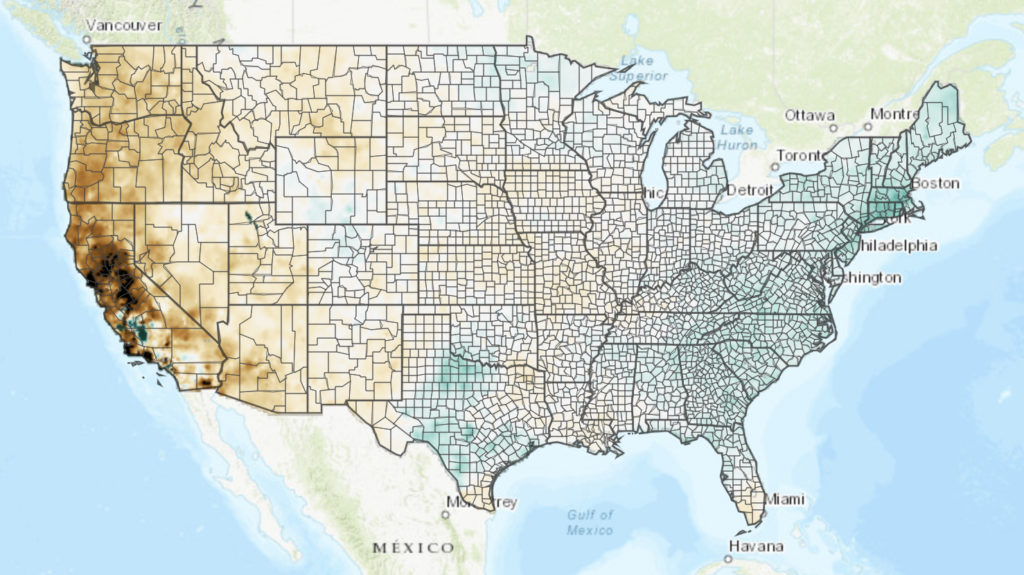

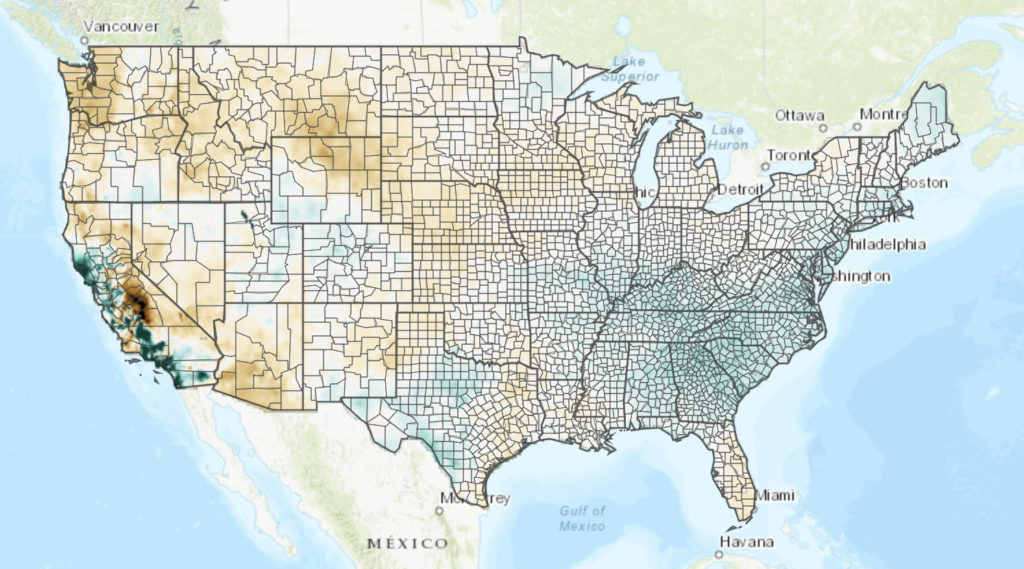

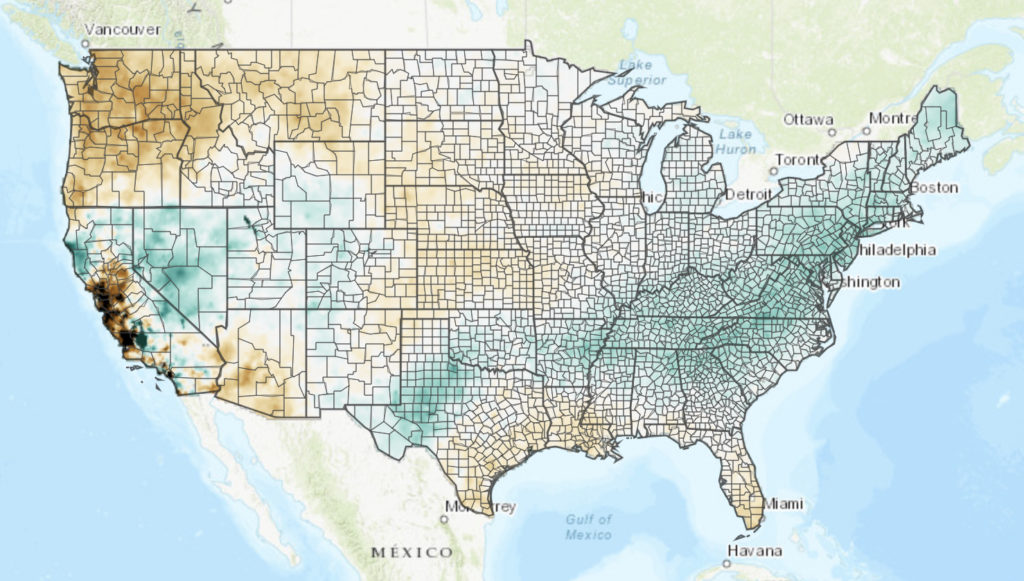

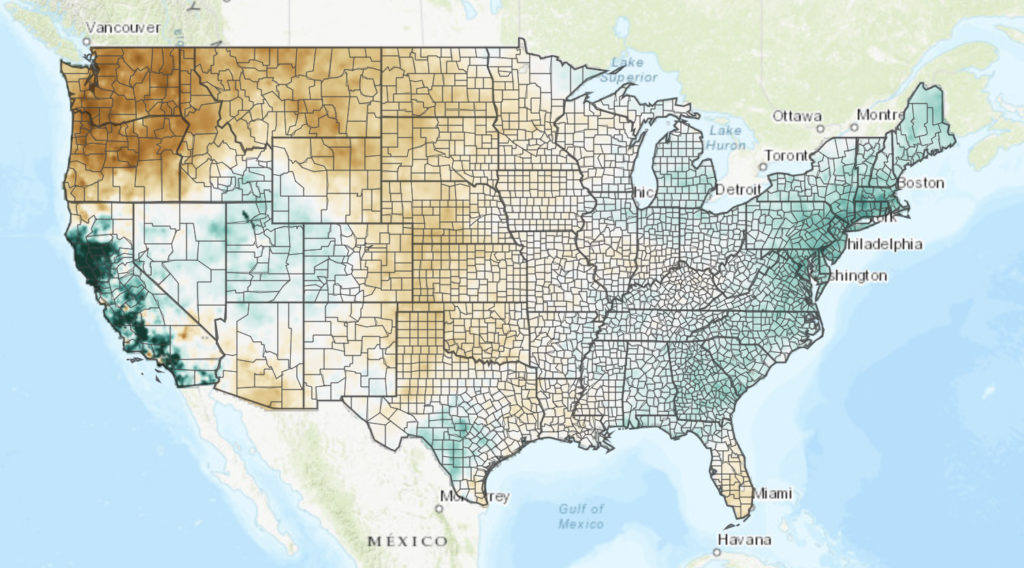

Corn harvested for grain across four USDA census years. Data retrieved from U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service.

The Panel

Dr. Lori Abendroth is a research manager and agronomist at Iowa State University, a position she has occupied for the last 14 years. She heads up a team of 140 people dedicated to developing climate change adaptation strategies for farmers in the Midwest.

Dr. Jerry Hatfield works for the United States Department of Agriculture as a supervisory plant physiologist and the director of a laboratory of 20 scientists. He analyzes the impact of the environment on agriculture and vice versa, keeping a close eye on how atmospheric parameters and climate variation induce stress in various plants, including corn.

Dr. Dennis Todey was South Dakota’s state climatologist for 13 years before heading to Ames, Iowa, to work as director of the Midwest Climate Hub, a branch of the USDA.

UP: What, specifically, is climate change changing in the Midwest, and how do you know?

Abendroth: In the future, what corn production will look like is an area that hundreds of scientists are working on. It’s difficult to ever try and narrow it down to just a couple key points, but what we do expect is that the climate will look different in the future, and models and projections [show] that we should expect warmer temperatures.

Hatfield: We looked at the yield gaps [attainable corn and soybean yield versus that actually obtained] relative to climate data—temperatures, precipitation on a monthly basis, etc. And what we find for the Midwest is that yield gaps are related to basically three parameters: July maximum temperatures, August minimum temperatures, and July-August precipitation.

UP: Let’s start with the first of those. Why do the maximum temperatures in July affect how much corn farmer’s get?

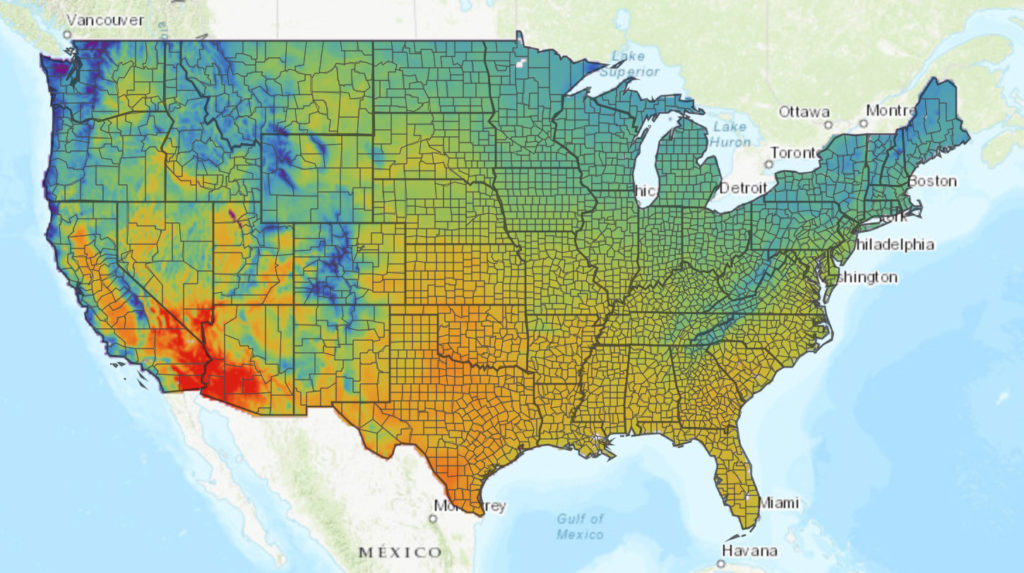

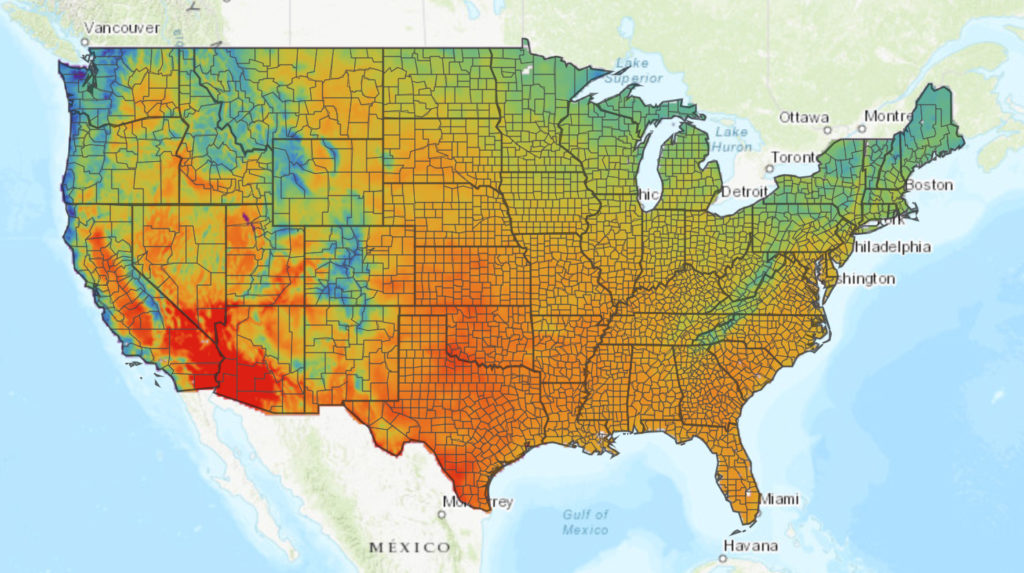

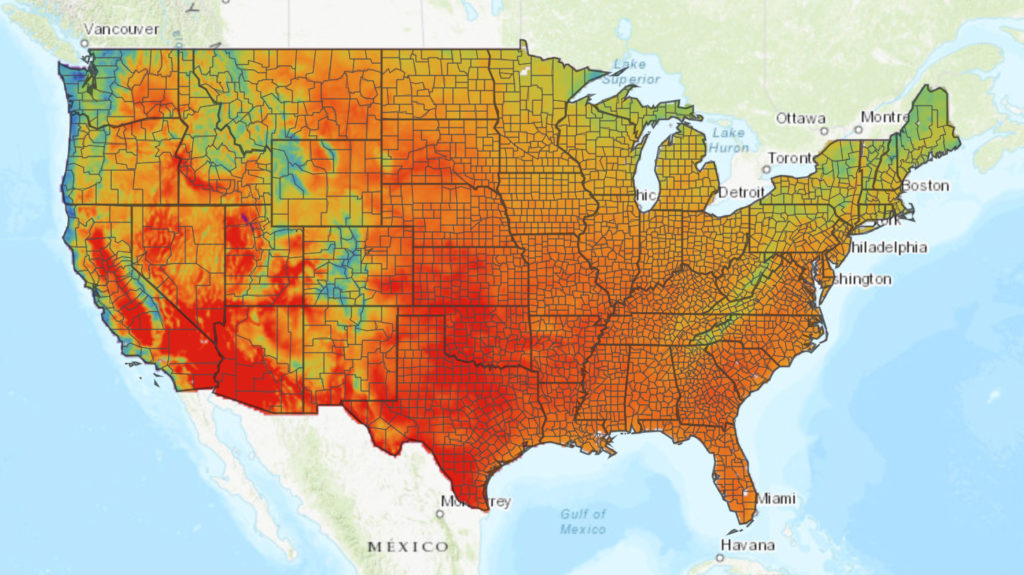

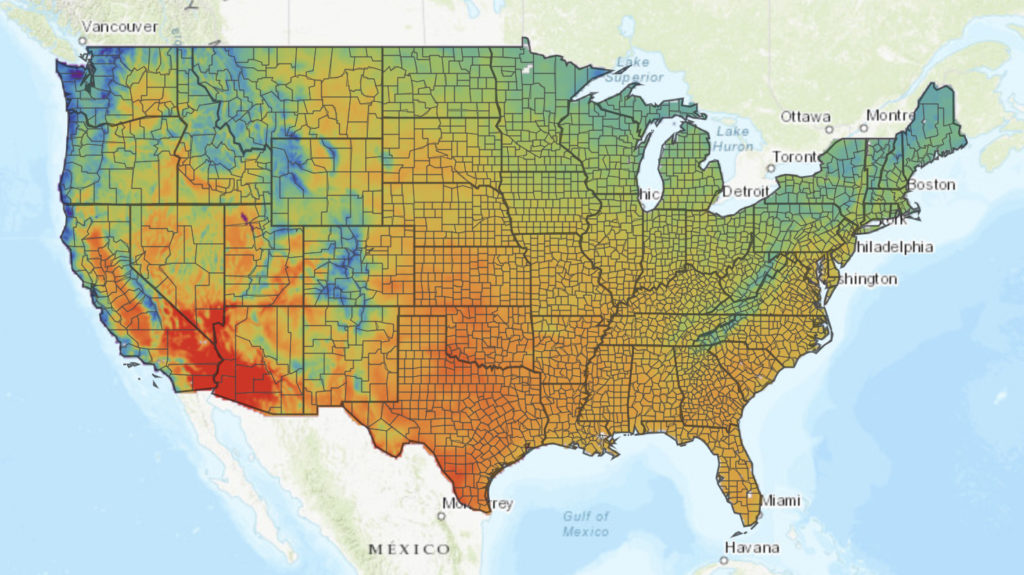

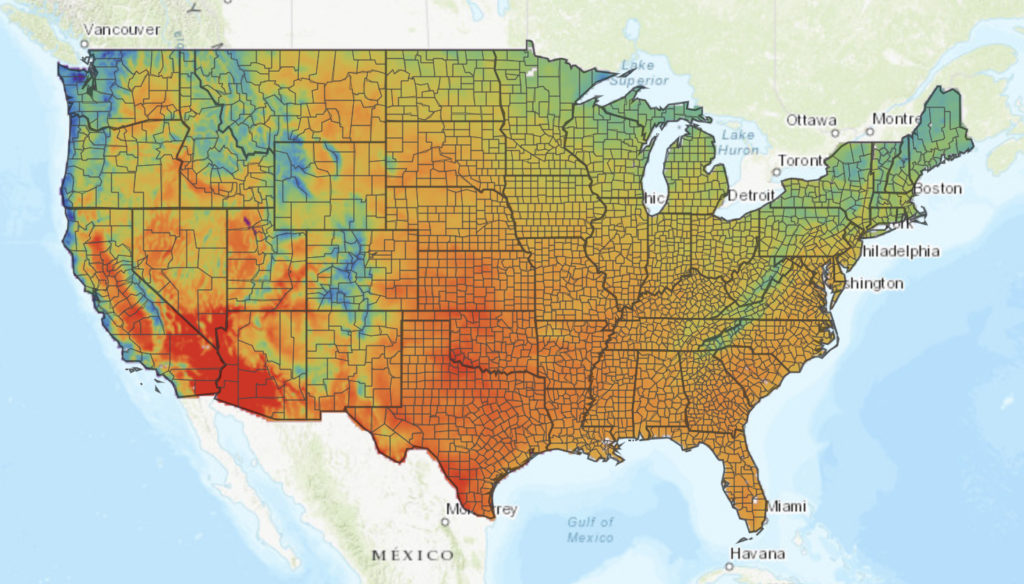

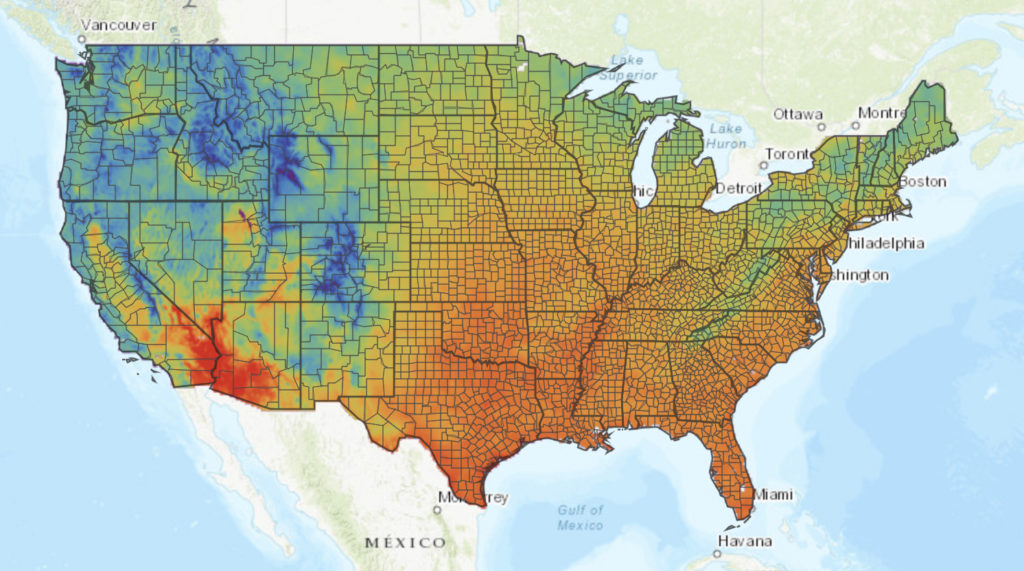

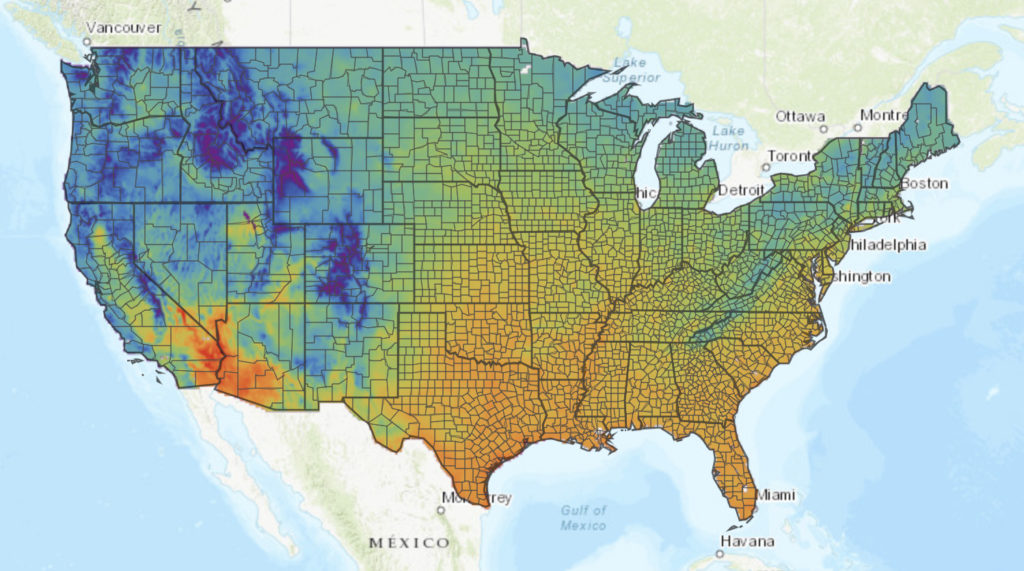

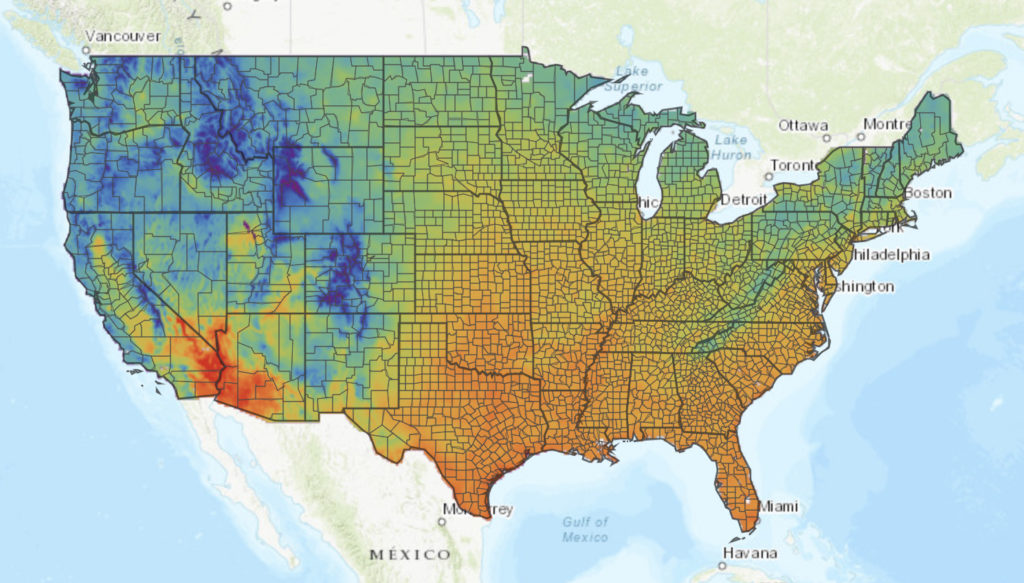

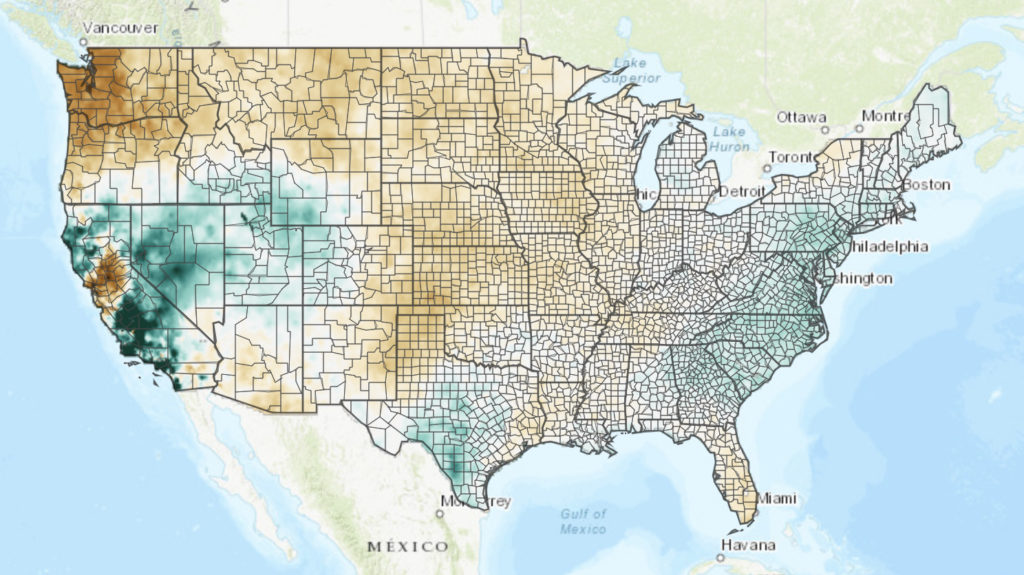

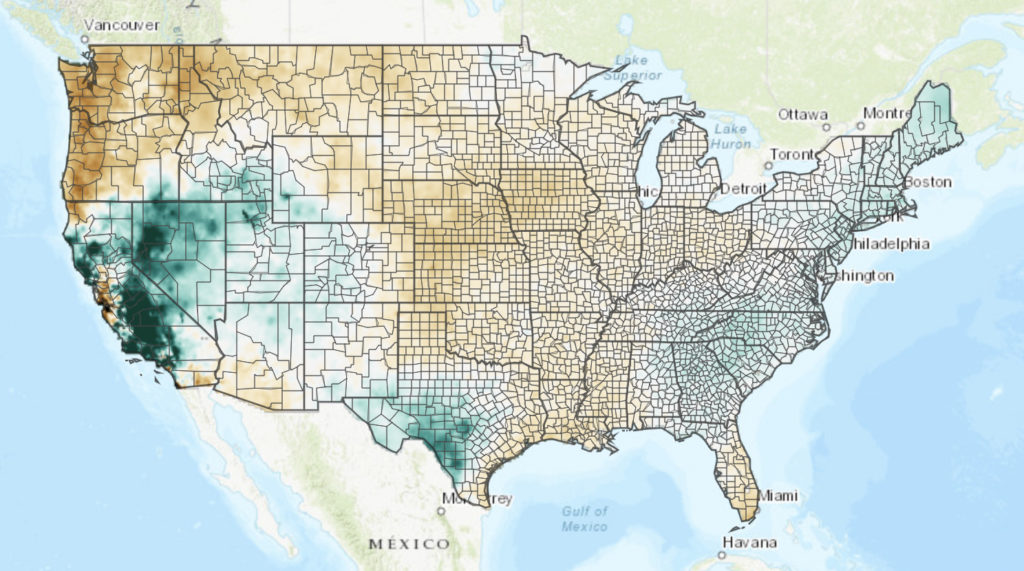

This animation shows the projected July maximum temperatures across the United States based on high estimates of carbon emissions in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

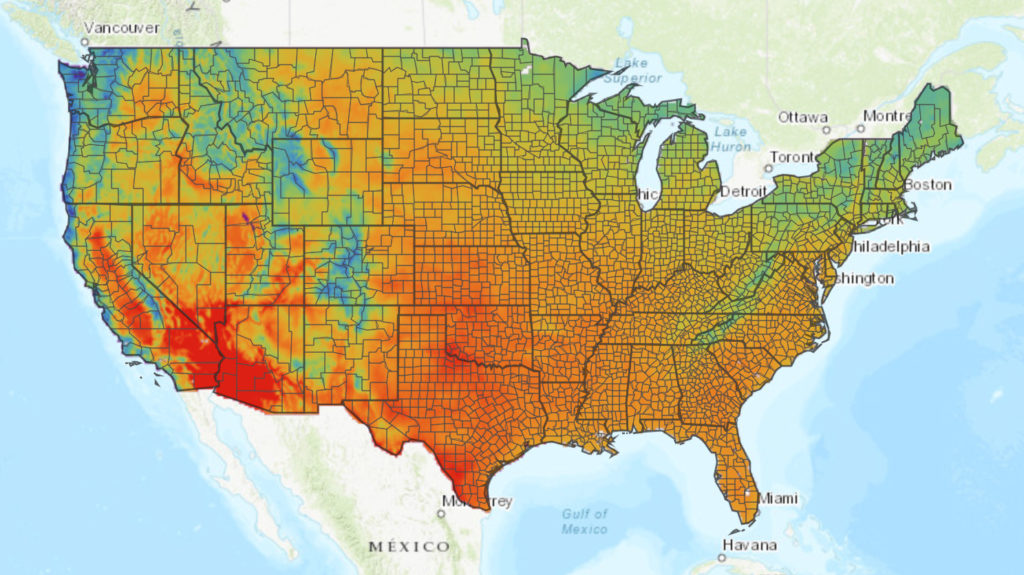

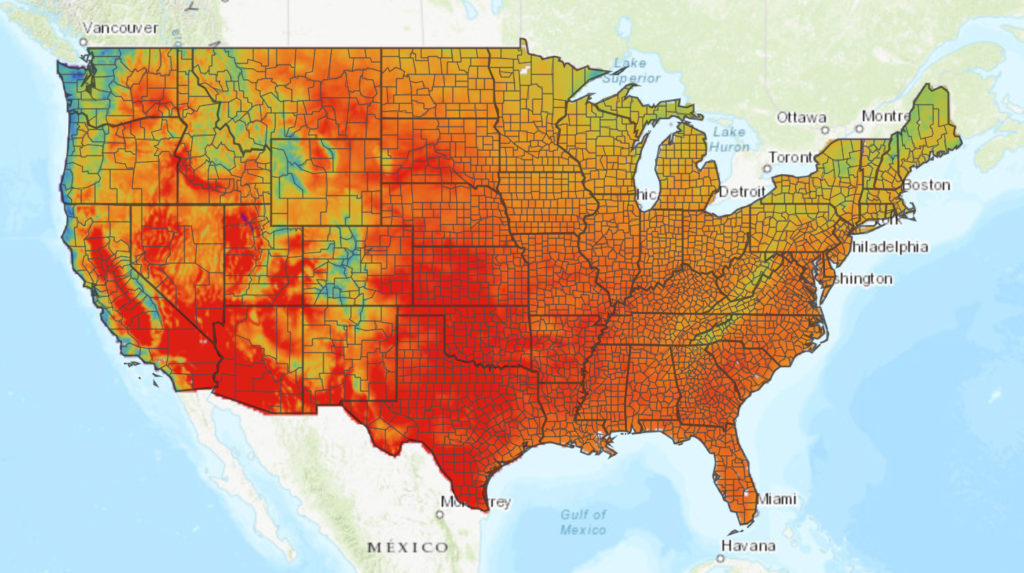

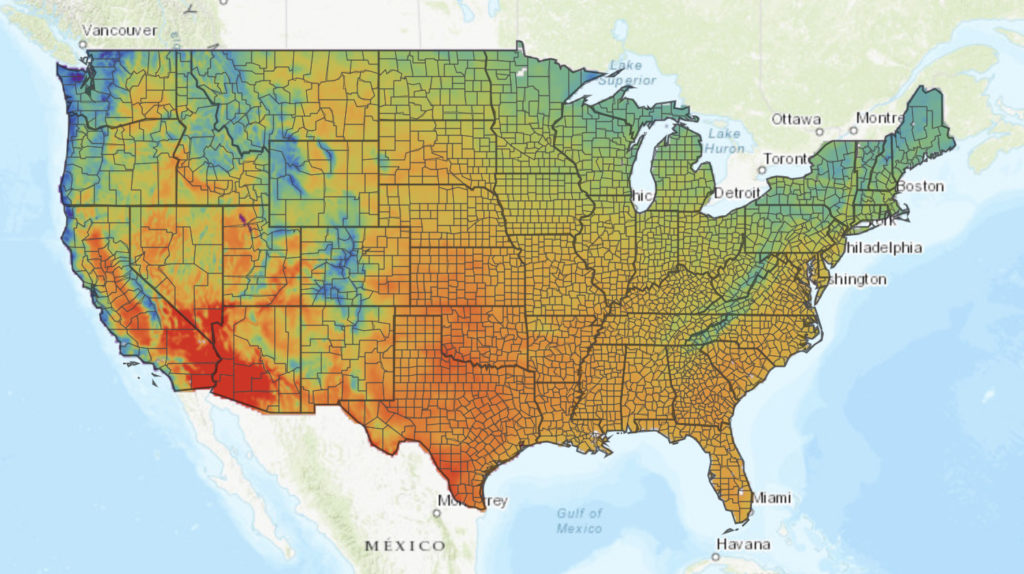

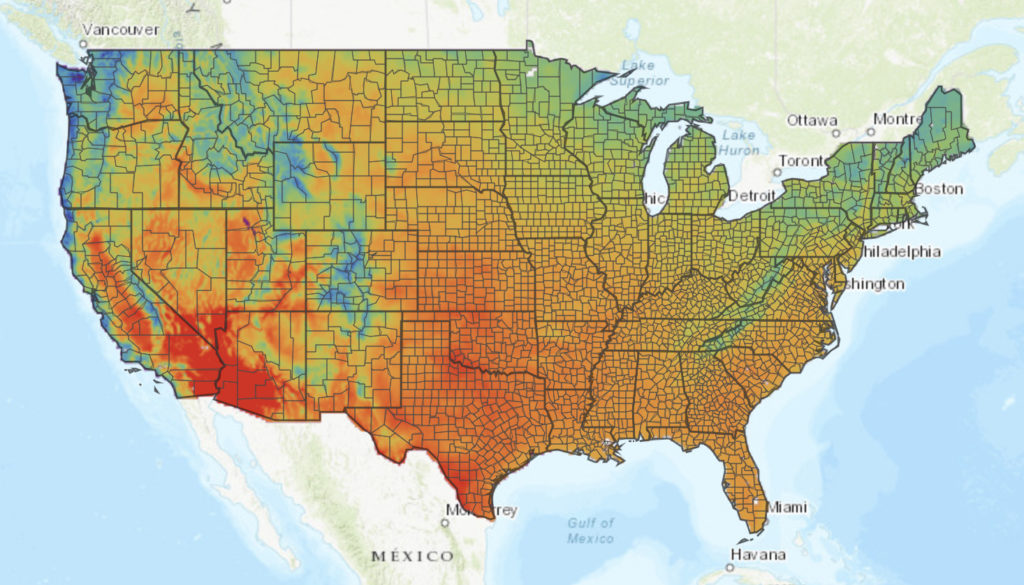

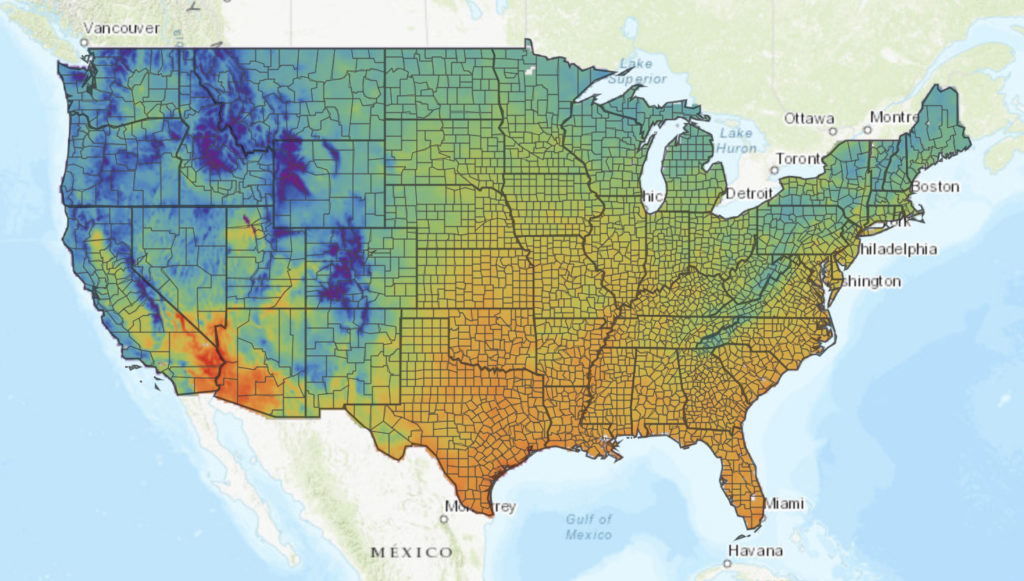

This animation shows the projected July maximum temperatures across the United States based on more conservative estimates of carbon emission predictions in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Hatfield: [July is] the time in which the plants are pollinating, so they’re shedding pollen and getting ready to move into reproductive stage. Pollen is very sensitive to high temperatures…Corn can handle temperatures up to—I’ll put in in Fahrenheit for you, because we generally deal with Celsius—they’ll handle up to 85 to 90 degrees. You get much above 90 degrees, it really will impact the pollination.

UP: What about August minimum temperatures?

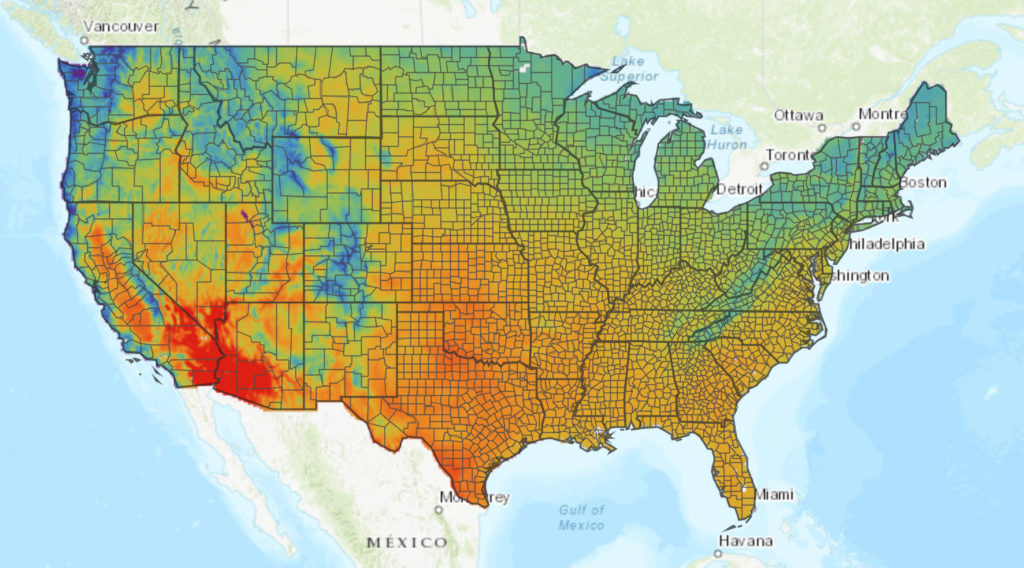

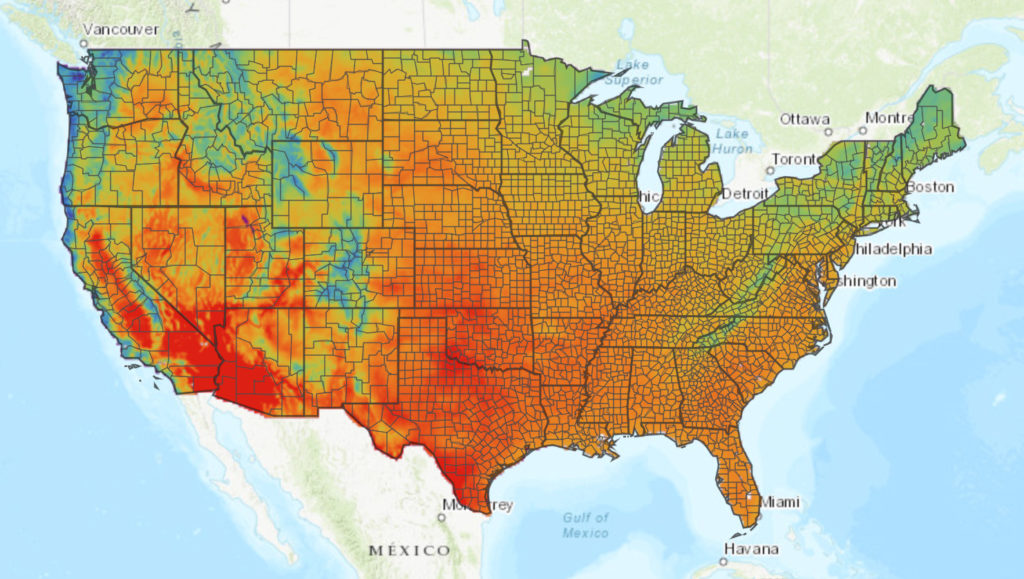

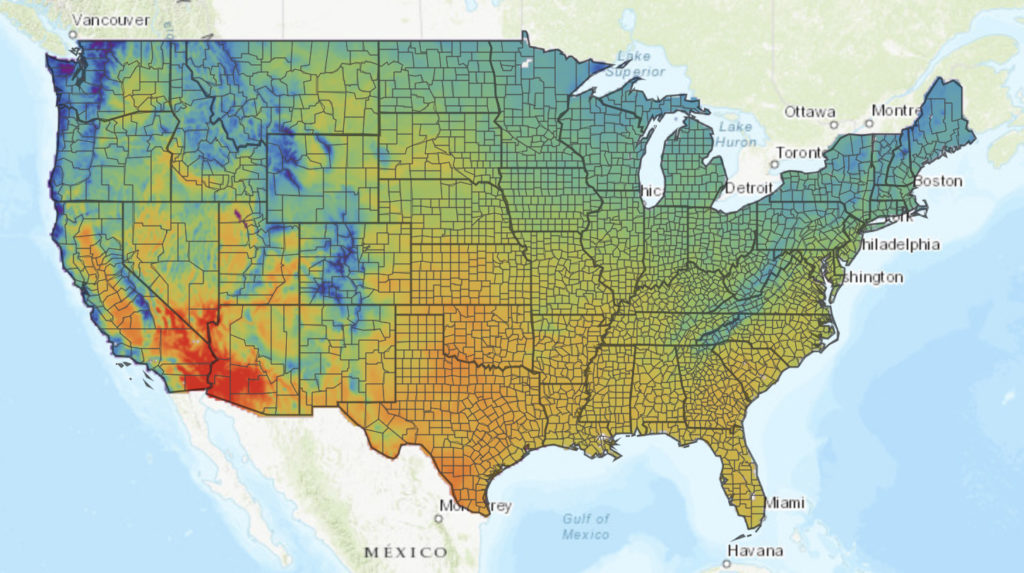

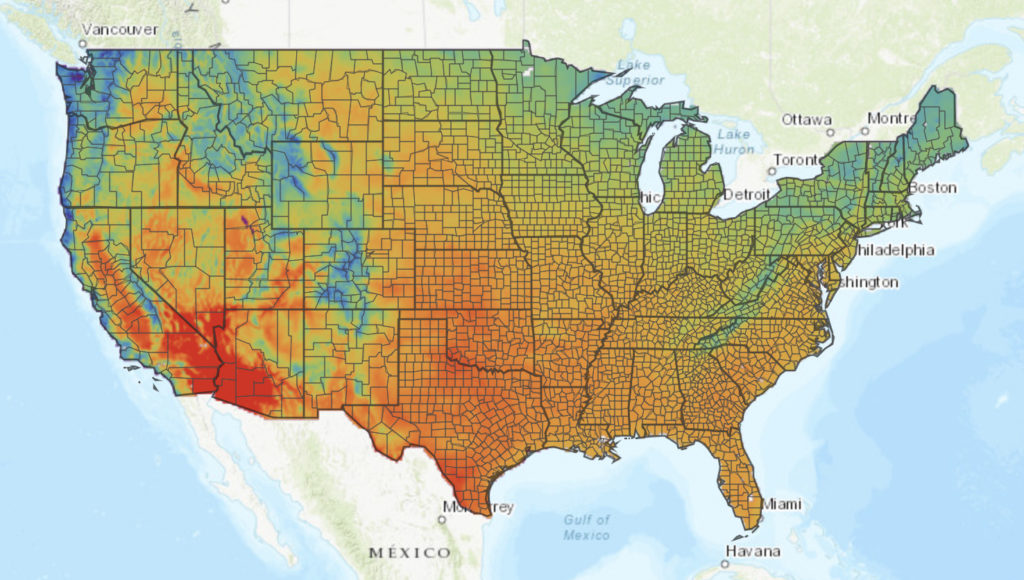

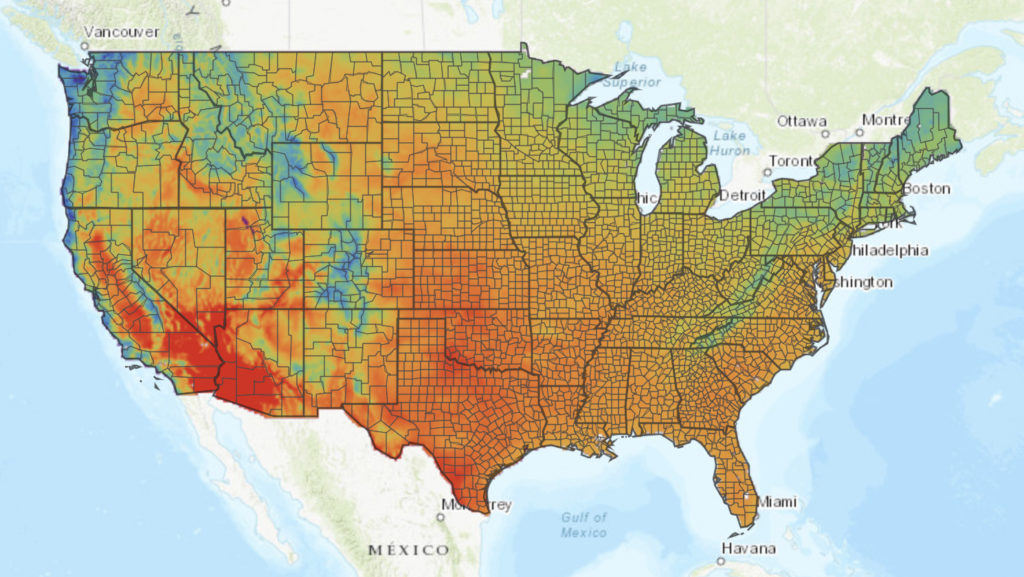

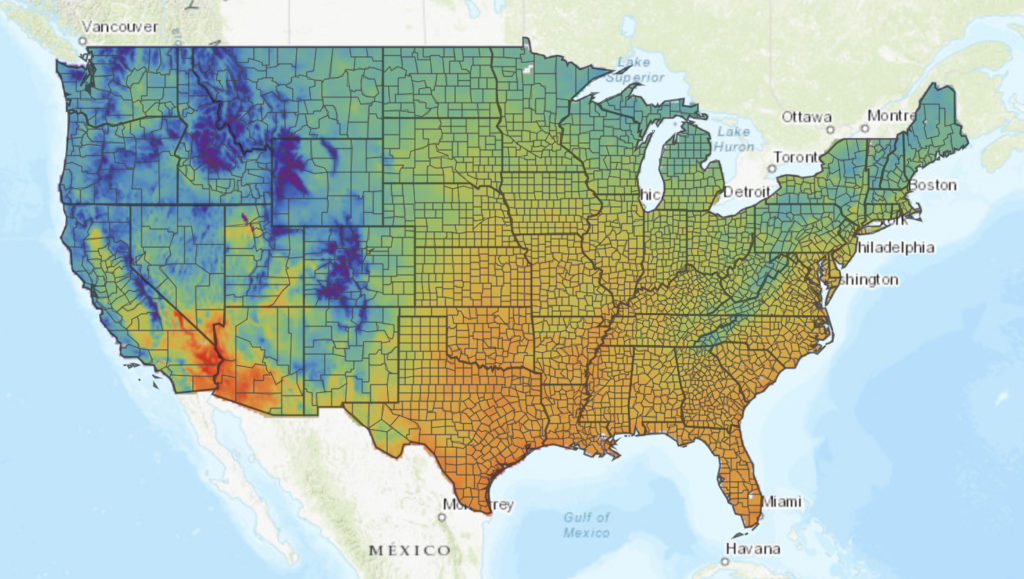

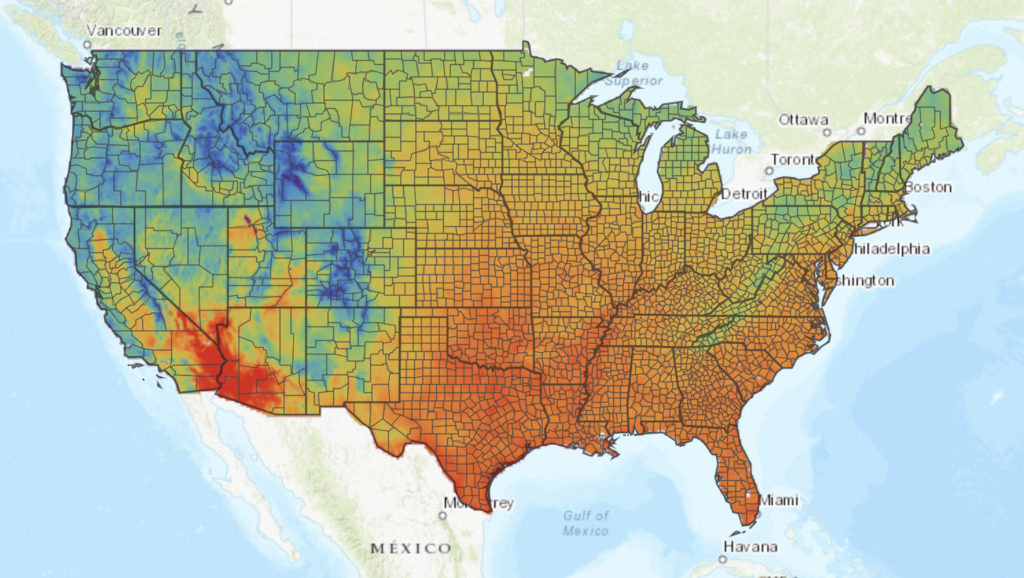

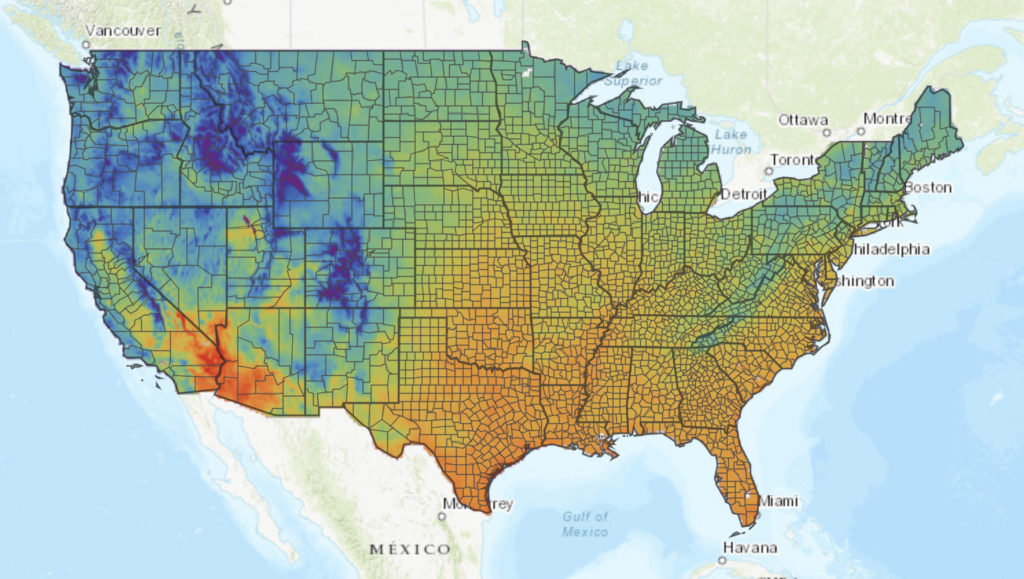

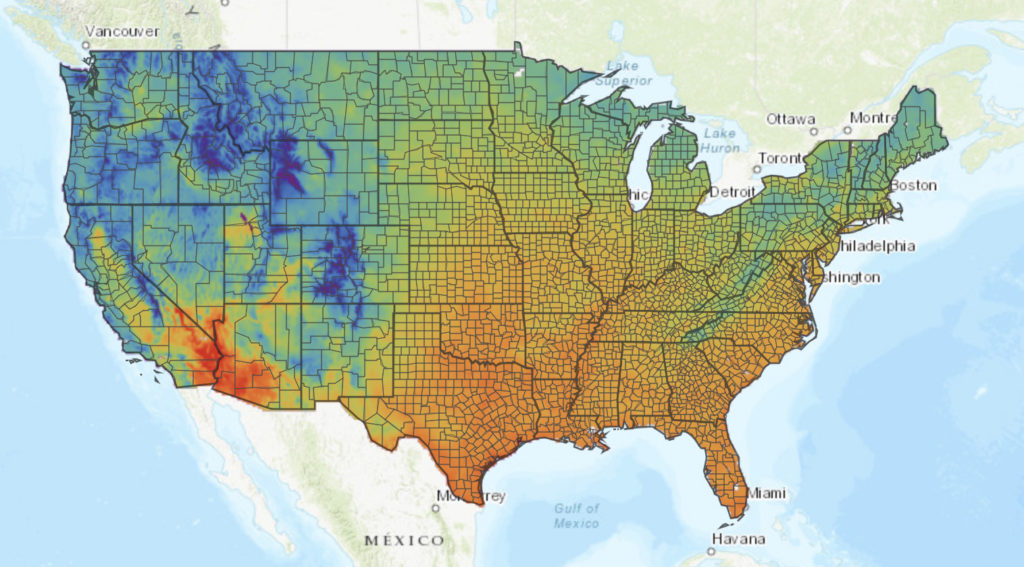

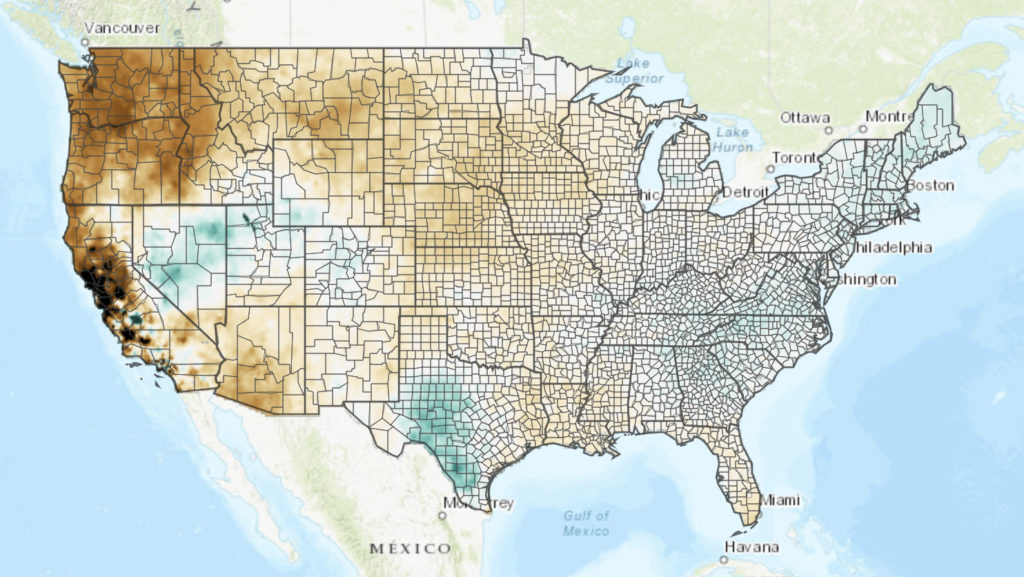

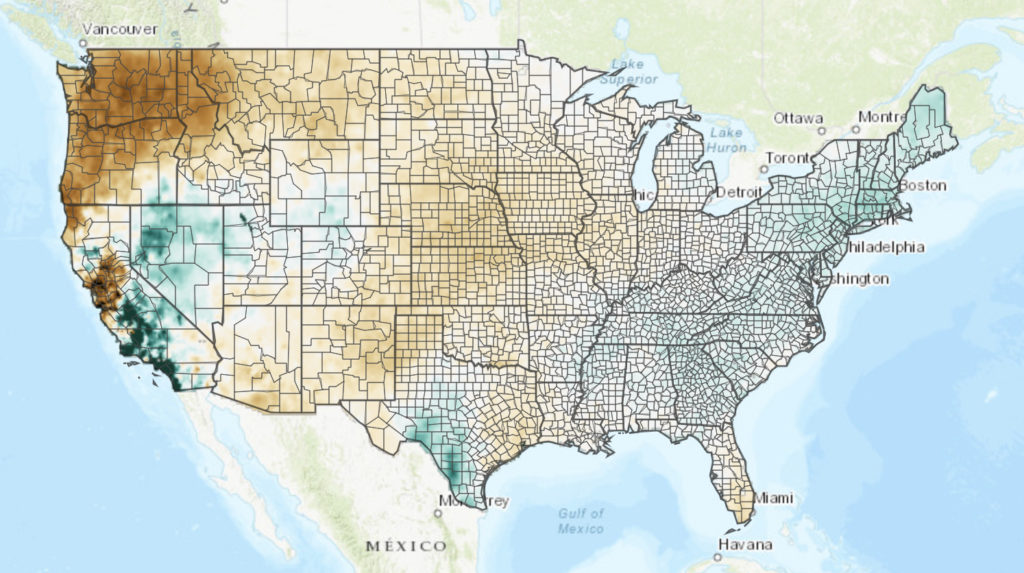

This animation shows the projected July minimum temperatures across the United States based on high estimates of carbon emission predictions in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

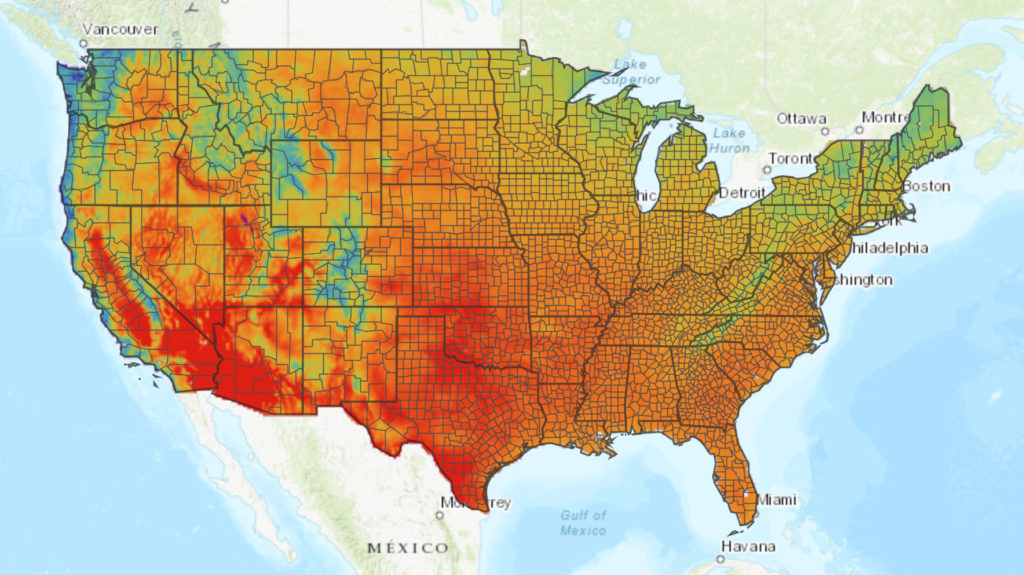

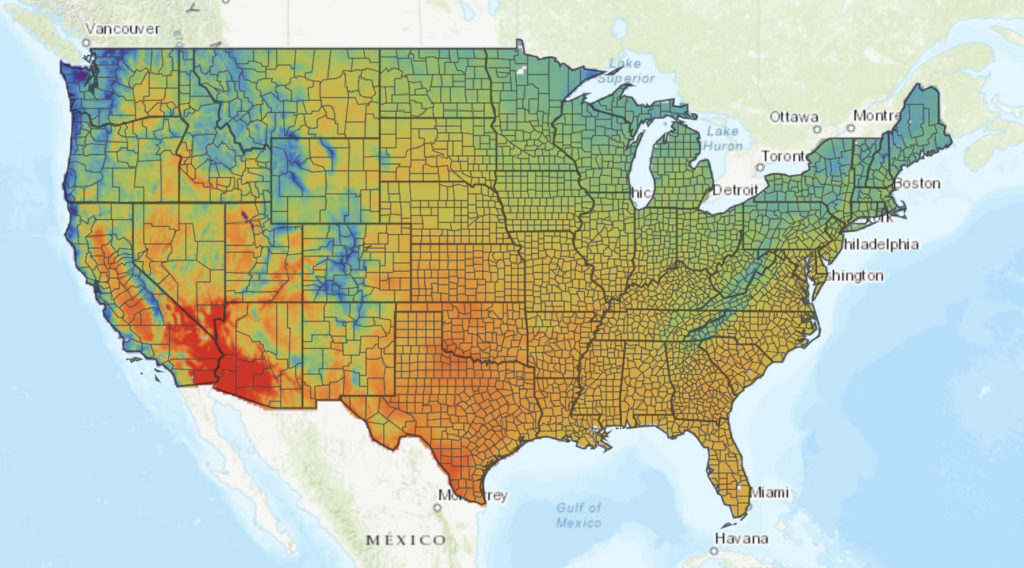

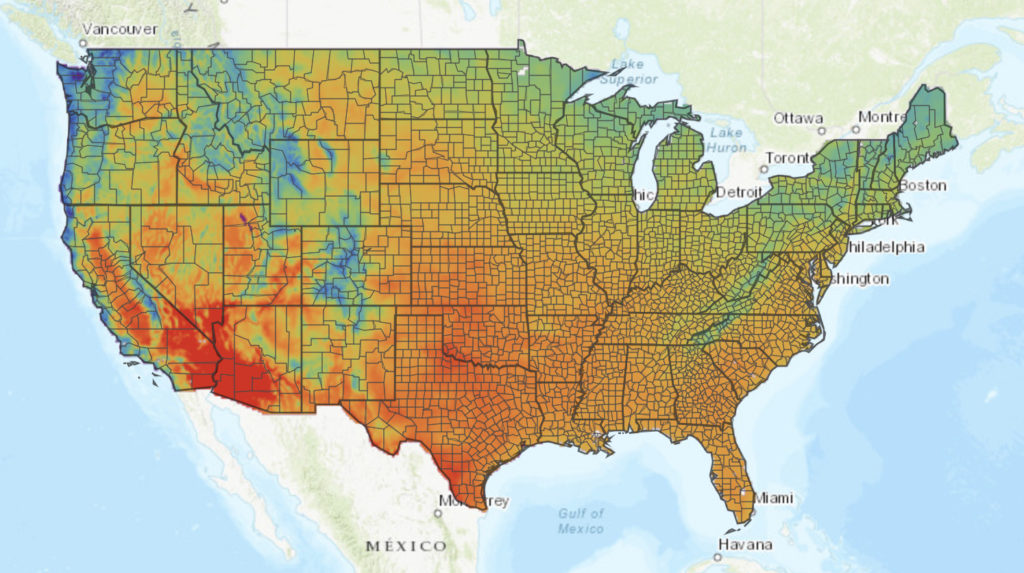

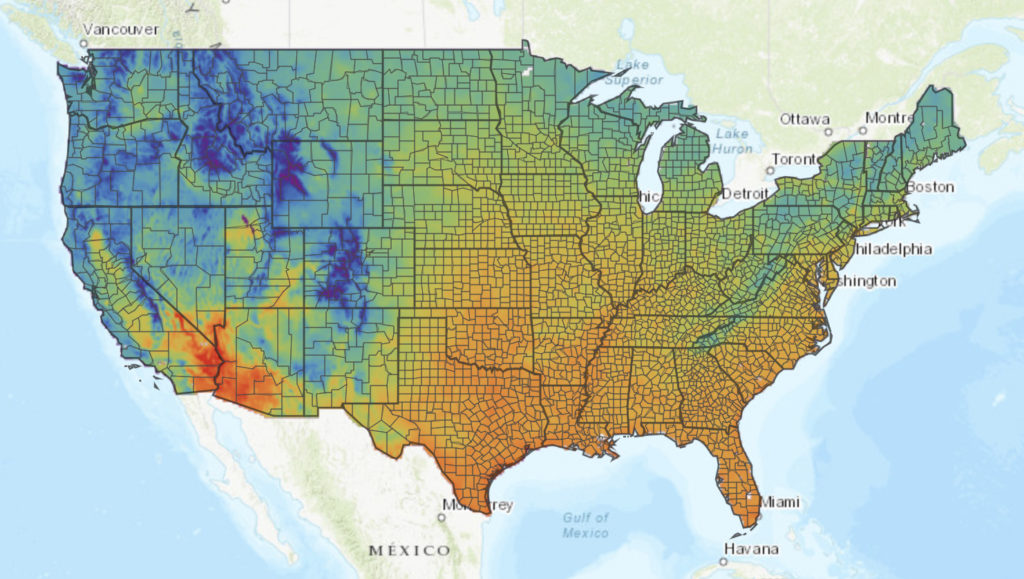

This animation shows the projected July minimum temperatures across the United States based on more conservative estimates of carbon emission predictions in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Hatfield: Years that have really high minimum temperatures in August are among some of our lowest yielding years. Physiologically, high nighttime temperatures do cause a stress on the plant, because what they’re doing in high nighttime temperatures is we end up with increased respiration rates at night. That makes the plant senesce [deteriorate with age] quicker, so they have a shorter grain filling period. They’re not as efficient in converting photosynthate [a substance produced by photosynthesis] into grain in that.

Todey: It makes the corn mature more quickly, so you lose a little bit of yield because of that.

UP: I thought more rain was good for plants. Why is precipitation a problem for corn farming?

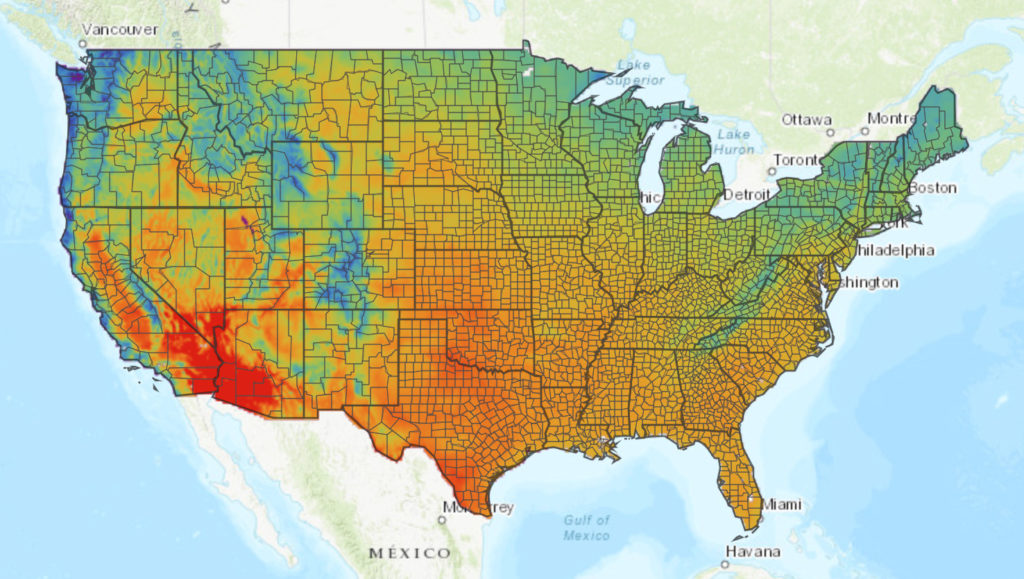

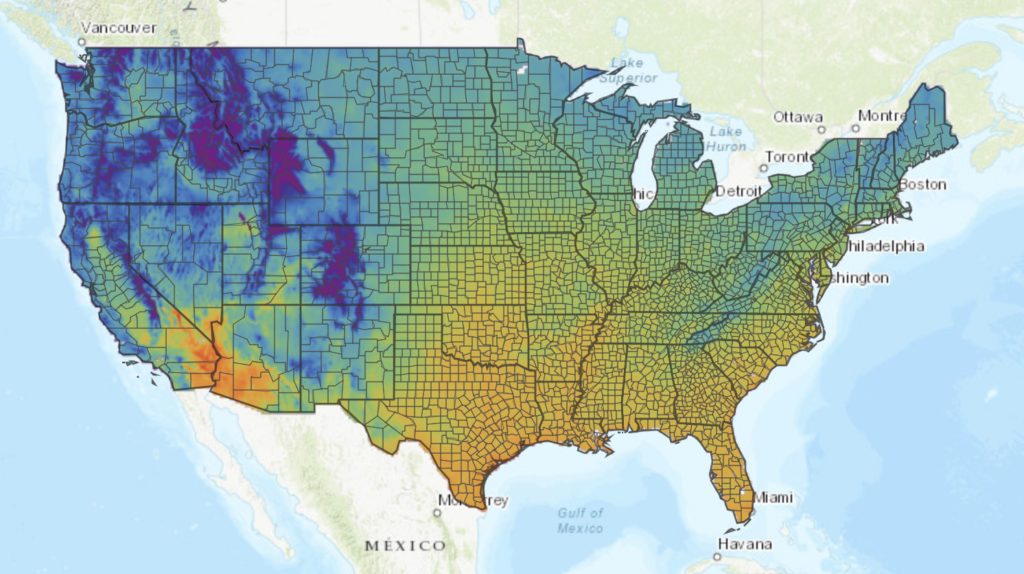

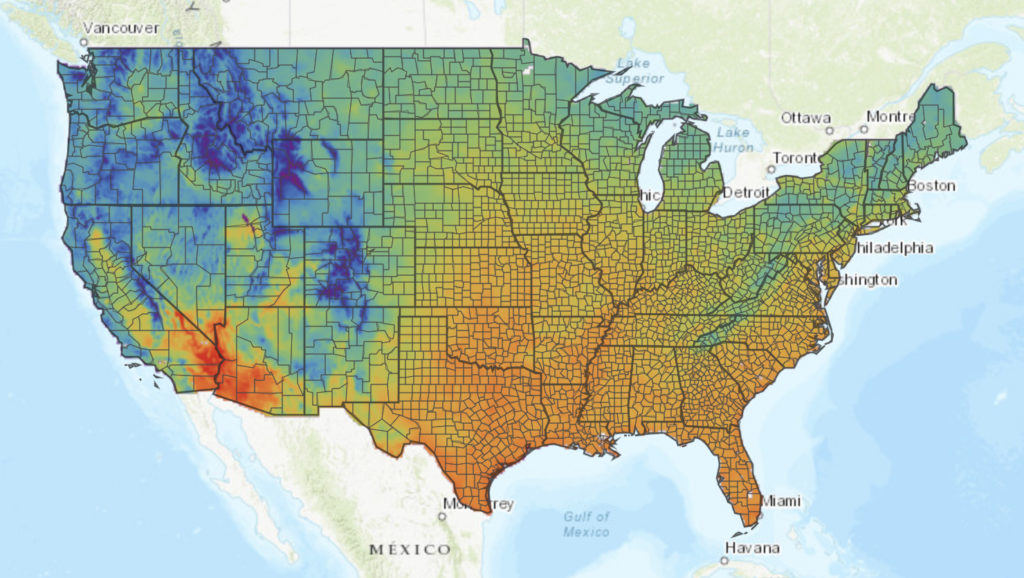

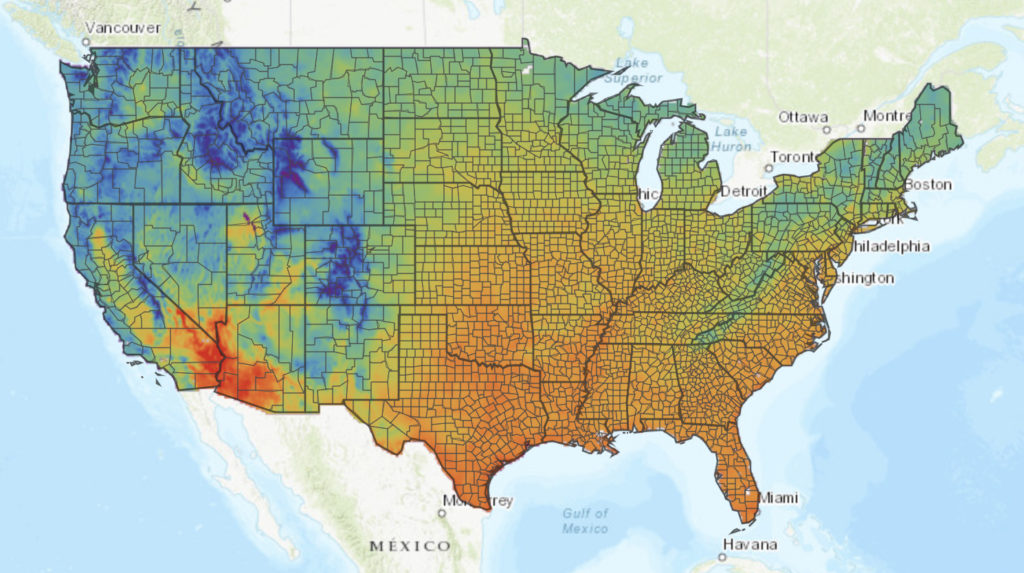

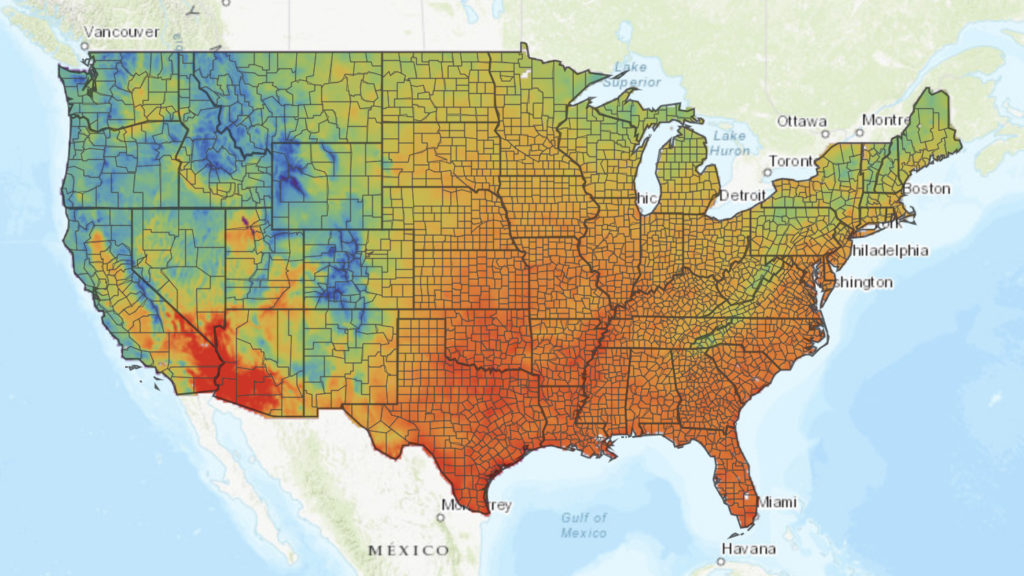

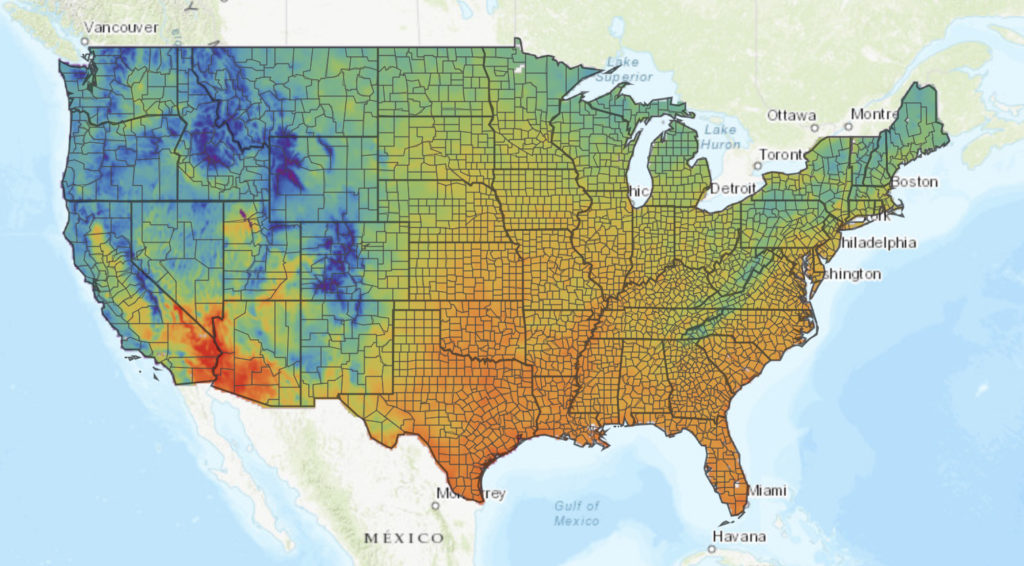

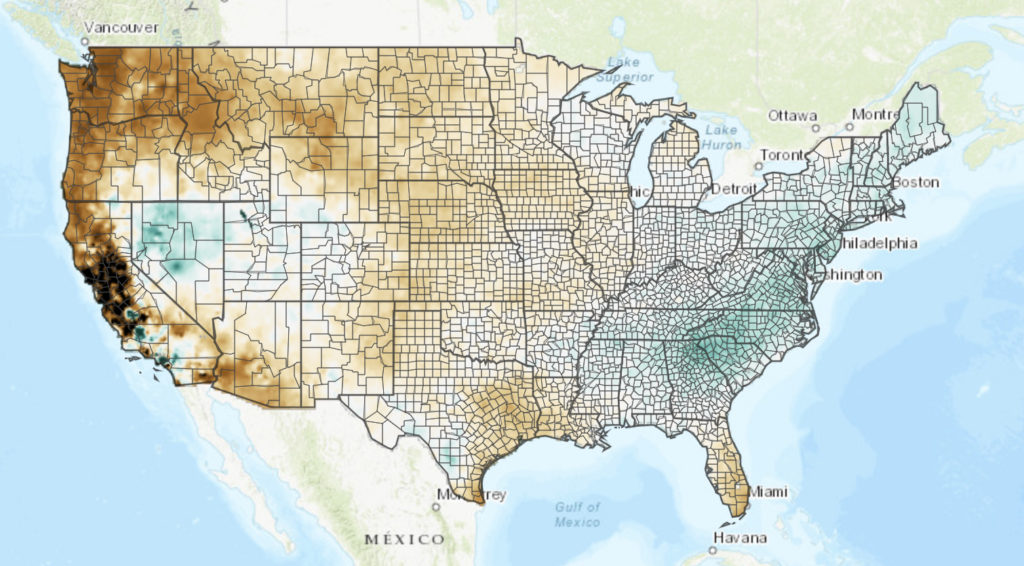

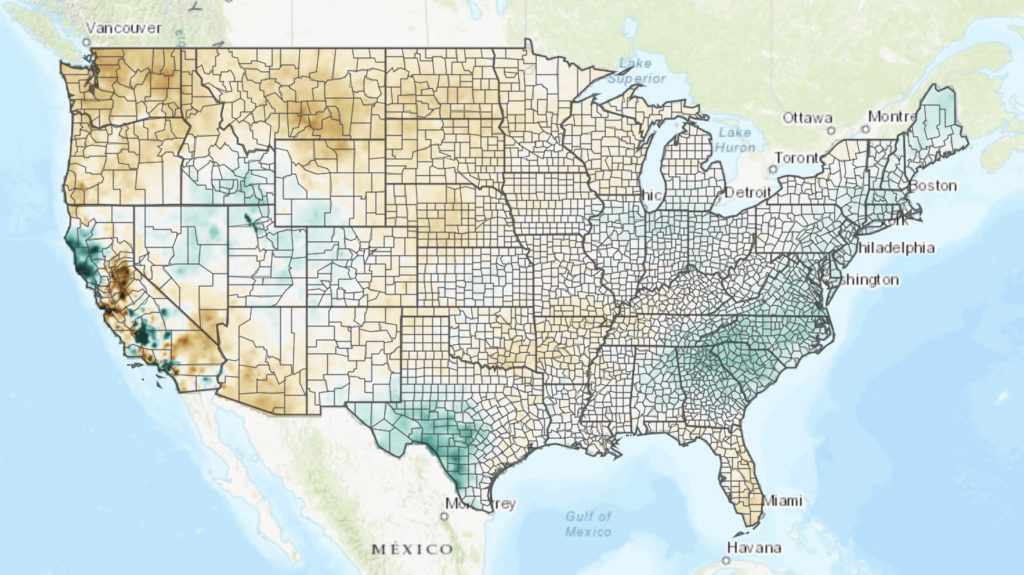

This animation demonstrates the total rainfall anticipated in July across the United States based on more conservative estimates of carbon emission projections in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

This animation demonstrates the total rainfall anticipated in July across the United States based on high estimates of carbon emissions in the next century. Data retrieved from U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Abendroth: What we expect in the Midwest is a change in the precipitation frequency and timing and intensity.

Todey: Like this year, we started off being very wet last fall, and then that carried over until this spring, so producers were not able to get out in the field and plant their crops on a timely basis. So, we had very poor developing, very late developing crops this year that really have slowed the whole process down. In addition, when you’re dealing with heavy rainfalls like that, you’re dealing with potential nutrient losses. Part of our water quality issues are due to extreme rainfalls washing more nutrients from fields into water bodies. Also, these additional rainfalls can lead to soil loss, so moving topsoil from where we want in fields to other places in fields to moving it completely off the landscape. So, there are problems with the additional heavy rainfalls that we’re dealing with.

Hatfield: Variable precipitation during July to August impacts both [corn and soybeans]. Somewhere in that six-to-seven-inch rainfall total during that period is good. We could get to eight; that’d be even better. You get any more than that, and you actually get the other side, and you start actually overwatering that plant, which isn’t good, as well. Part of the reason for that, and that’s the reason why it’s so complex, is the more rainy days we have, the more cloudy days we have, the less solar radiation we have, and that’s what really takes the drive [out of] the photosynthetic process. A lot of these things are all interrelated. And so that’s why it becomes a really complex puzzle to start looking at.

UP: What are some other factors to take into consideration?

Todey: Certain weeds are very effective at using carbon dioxide, so you have weeds that become more difficult to control and become more competitive with the beneficial crops. You also get into insect issues when you have overall warming issues. There are insects that don’t die over winter here—and when you have warmer winters, they still may be killed off over winter further north, and they’re more easily reintroduced every year. Also, during longer growing seasons, you may be able to get an extra lifecycle out of whatever insect it is so that it’s not only an issue once a year, it’s an issue two or three times a year.

Abendroth: The temperature is not changing uniformly across the whole year. Precipitation is affecting our temperature increases. [And because of] some of the other aspects in terms of the insect cycles, increased humidity, and then warming overall, we certainly are seeing the Corn Belt migrate to the northwest slowly.

UP: So, how are these specifications of climate change going to influence the Corn Belt?

Hatfield: What we’re going to see is a shift in the Corn Belt. You know, you think of the Corn Belt going from roughly Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Minnesota. But we’re seeing that shift, moving north and west into North Dakota and South Dakota.

Abendroth: We’re continuing to add acres up in the Dakotas and Minnesota and Wisconsin. The Corn Belt is certainly slowly moving north, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re losing acres in the south yet.

Todey: We haven’t seen too much recession in the southern part of the Corn Belt, but there have been a bit more struggles from year to year. At some point, the economics are likely to change, and when you start having more problems growing corn, you’ll start thinking about something else. There is modeling that has shown that, with projections in the way temperatures are headed, corn and beans will be tougher to grow in the southern parts of the Corn Belt.

UP: Just how much, exactly, will climate change influence the corn industry?

Hatfield: Those three parameters—July maximum, August minimums, and July-August rainfall—tend to be the factors that affect both corn and soybeans across the Midwest. Those are the factors that are changing very rapidly with climate change…People have run crop simulation models and put into simulation models what the projected July temperatures are, and August temperatures, and variable rainfall, and we find out that corn yields are going to decrease, maybe 10 to 12 percent. Sometimes more than that, depending on how severe you run the scenario. All indications are that our productivity across the Midwest is going to decrease because the increasing weather stress during the growing season is going to impact that crop.

Abendroth: Climate change is really increasing the risk for farmers and increasing the intensity that they need to be managing this system. By intensity, I mean the stewardship and mindfulness of the challenges that they face and proactively coming up with solutions to address those challenges. They’re very resilient in the way they manage their systems, meaning they are very interested in adopting some of those practices on their farms and what that could mean for their bottom lines, their long-term stewardship in being able to pass the farm down generations. A lot of these are managing for the short-term risk as well as thinking about the long-term health of their lands.