The commercial ice making process uses a lot of plastic. For every crystal-clear ice cube or block that’s crafted, the machines and ice trays are coated in a new sheet of plastic. Chicago’s Just Ice custom designs ice for local restaurants and bars, and a new sheet of plastic is used to ensure the proper growth of the ice crystals. Instead of just recycling the large amount of plastic that accumulates, Just Ice gives it to a nearby nonprofit, Plant Chicago, which uses the plastic to make reusable grocery bags for patrons of its Saturday farmers’ market.

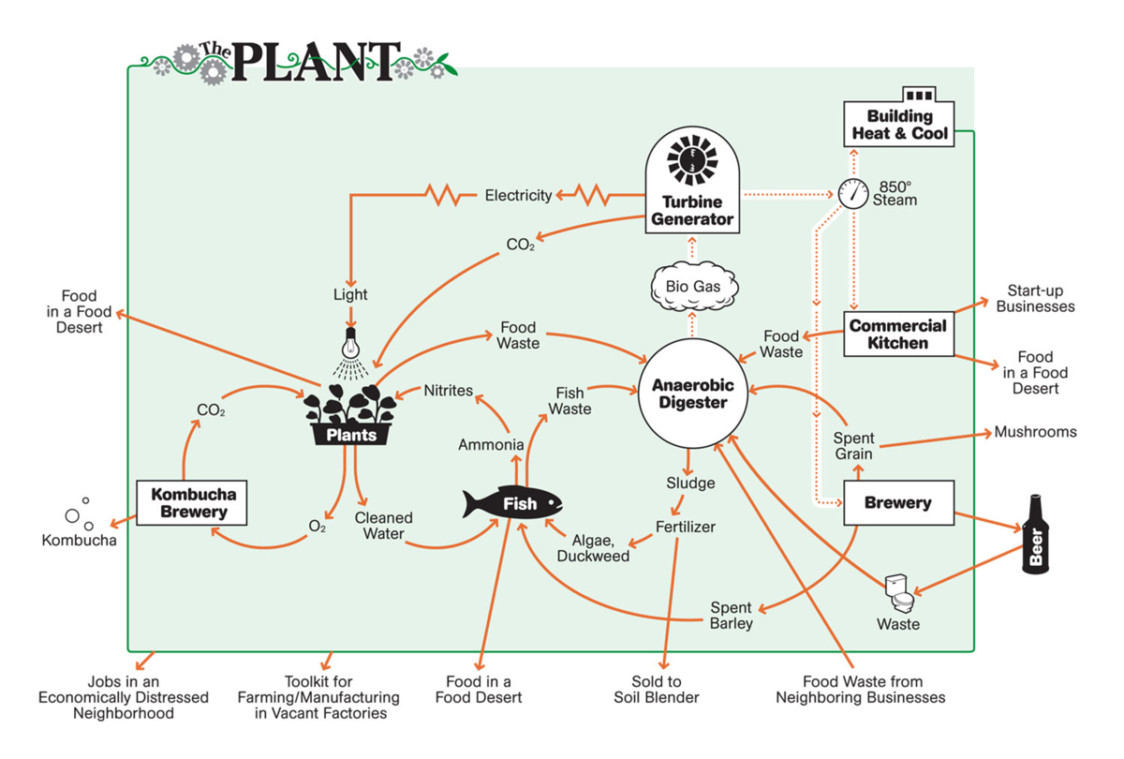

Nearby, in this case, is actually just upstairs. The building these companies reside in is called The Plant, and its mission is to be a sustainable food production hub that operates with closed-circuit energy loops — the waste created by one company is utilized by another. Being a zero-waste production company is a lofty goal, but with a collaborative community of 19 small businesses working toward that goal, their model has come a long way in eight years.

The loop might begin with Whiner Beer Brewery. Their waste water is used by another small business, BTRFY, to make microcrisps, a healthy alternative to potato chips, made with a mushroom fungus. The leftover spent grain used to brew the beer is taken outside to an urban farm area and fed to the chickens. The heat from the brewery is carried through pipes leading to the basement where the indoor plant farms require a wet and warm temperature as they bask under LED lights. Fish bred in the aquaponics farm are kept around to produce waste that breaks down into nutrients used to help the plants grow.

And so the energy loop is closed. Waste isn’t escaping from this five-story industrial building. Energy is radiating throughout its walls. In the grand scheme of things, The Plant is a small production facility in the Back of the Yards neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, but it’s working to change the culture of sustainability worldwide, from education to implementation.

“What we have right now is a linear economy. It’s based on the the idea of take, make, and dispose,” says Eric Weber, technology director at Plant Chicago. “We take resources out of the ground, we make something out of those resources, and then at the end of a product’s lifespan, we throw it away and take more resources to make the next product.”

In a closed-circuit economy, that line becomes a circle — all the materials in a product should be able to be reused, repurposed, or recycled. The Plant calls it their replicable model. “Use what you have, not what you wish you had,” says John Edel, owner of The Plant and the visionary for the project.

Evolving History

Edel is the founder of Bubbly Dynamics, a for-profit social enterprise dedicated to urban redevelopment and the creation of replicable ecological models, which bought The Plant in 2010. He acquired the industrial building as a “strip and rip,” meaning the inside was deteriorating to the point where the steel and copper could be salvaged and the remainder would be demolished. But Edel saw tremendous energy sitting unused and decided to carry out his vision with the building as is.

The energy was leftover from The Plant’s past in food production. In the 1920s, the Back of the Yards neighborhood was Chicago’s famous union stock yards and The Plant was a meatpacking facility.

Edel bought the 93,500-square-foot building for $500,000. The price was one incentive, but the bigger draw for Edel was the building’s past. “It was a pork packing plant, so it’s a food grade building,” says Edel. “The brick floors, the floor drains … this was an obvious place to do small food business.”

The businesses began funneling into The Plant solely by word-of-mouth. The project has generated a lot of press which has attracted businesses, Edel says. As have the inexpensive leasing prices.

The food production businesses housed in The Plant are dispersed throughout its five floors. The basement is home to four businesses and an indoor garden. The main floor is the brewery — its taproom, brew house, and cooler space — and Pleasant House Pizza. The second is home to nine businesses, the milling room for the brewery, and the new home of the Packingtown Museum, which celebrates the history of the Back of the Yards neighborhood. The third floor is a collaborative education space that Plant Chicago utilizes for workshops, and an algae science lab for research purposes. The roof houses beehives and is a communal composting area for the businesses. Urban gardens owned by the farming businesses can be seen dotting the mulch below — a wide range of flowers, vegetables, and the occasional roaming chicken.

Businesses have filtered in and out since the project’s start in 2010. Some have left due to expansion; they needed a space larger than what The Plant could offer. Others left because the space didn’t fit the demands of their business models. The Plant’s model benefits small, startup businesses, although a few were established prior to leasing in the building. Currently, it is 80 percent occupied, and all the businesses are working toward the closed-loop system of sustainability.

Since money was tight at the project’s start, much of the building’s history is preserved — a standout being the meat smoking chambers, now repurposed into bathroom stalls for the tenants. Edel graduated college with a degree in art, so he has enjoyed the side project of repurposing the industrial building to fit the mold of what his tenants need.

But Edel is also providing what the community needs because the circular economy doesn’t just relate to food production. By repurposing the building, he brought healthy food options to the neighborhood, which is registered by the census as a food desert, and saved the land from becoming high-rent, luxury condos — often the first step in gentrification.

An Actionable Model

“Any time you do something unusual or interesting, people will show up,” Edel says. “It’s really about building community, and giving people, not free reign, but the ability to take a project and trusting them to do something with it.”

Bubbly Dynamics and Plant Chicago — the nonprofit housed inside The Plant — have been the glue that brings all the food production businesses together. They work with businesses one-on-one to figure out ways their waste can be utilized.

“It’s about providing the structure to allow collaboration,” says Carolee Kokola, director of enterprise operations for Bubbly Dynamics. A common byproduct that usually escapes from the brewery is CO2 emissions, but the algae farm and other farms can utilize that gas. “We connect those dots and Bubbly installs the infrastructure that moves the CO2 to the farms.”

Plant Chicago offers workshops to the tenants on how to be more responsible with their waste — from simple steps, to composting, to intricate things like limiting their plastic usage. Most of the businesses practiced sustainability prior to joining the project at The Plant, but they have since learned new ways to reuse their own waste or recycle it to another business.

“Coffee beans produce a waste called chaff, which is this light, airy, fluffy, popcorn-looking flake,” says Michael Peters, the production roaster for Four Letter Word Coffee, a 2-year tenant of The Plant. “At the very least, we compost that, but we’ve played around with sending it down to be used in the aquaponics farm, and using it to make a bio-briquette in conjunction with a bakery that used to be here.”

Peters says the number one thing he’s learned since becoming a tenant is that being a zero-waste company is tough but attainable.

These things take time. Edel knows this is a slow money project — get a tenant in, make money, reduce waste, sell model. All the money made is put into the next step, and therefore the project operated for many years with little to no leftover money. The Plant is Bubbly’s second project, and much of the income from their first project helped propel this one as tenants settled in and began operation. After close to six years, The Plant is finally operating in the black.

The end goal is to put this zero-waste model in front of companies that hold the power for change in their hands. “Part of the goal is to prove that if we can do it for almost no money and reach this level of sustainability,” says Edel, “How come corporate America is incapable of getting there themselves when they have tons of money to spend?”

A Fresh Take on Education

Beyond practicing closed-loop production, Plant Chicago spreads educational efforts into the community through farmers markets and hands-on workshops.

“The farmers market isn’t just a place for people to shop, it’s a place of support for the local businesses in the community,” says Liz Lyon, the farmers market coordinator for Plant Chicago. “We have five vendors from the Back of The Yards neighborhood, and this gives them a place to make money when they can’t get into grocery stores like Whole Foods just yet.”

One of the vendors, Star Farm Chicago, is located in Back of The Yards and uses the market as a networking and outreach opportunity. “For us, being here is about spreading our message and finding customers. It’s less about the actual sales,” says Cornelius Hodges Jr., Star Farm’s market liaison. “A lot of people just don’t know about us.”

The farmers market happens once a month on Saturdays from 11-1 p.m. Vendors are centralized in the lobby of the building. Some tenants of The Plant open up their stores for people to explore and shop. The inviting dining area in the brewery, lit by twinkling lights and decorated with tabletop plants, is a gathering place for most visitors during market hours.

Whiner Beer Co.’s inviting atmosphere makes it a social hub during Saturday Farmers Market days. The brewery is open for business, people can order pizza’s from Pleasant House, and vendors sell fresh food along the opposite walls.

The market accepts Link Match, meaning Plant Chicago will match dollar for dollar what you spend up to $25. “You can swipe your card for $25, we’ll give you $50 to spend,” says Weber. “It can help in these lower income communities offset the relatively higher costs of produce.”

The Plant is trying to revitalize the urban community it’s a part of, while perfecting the circular economy model in hopes that it will catch fire with other small businesses all the way up to large corporations.

“The Plant focuses on the small scale first,” says Weber. “That’s often what’s left out of the conversation … What are the little steps that we can all take that can theoretically make a very big impact?”

It starts slow. And it starts small. Edel, a man with grandiose ideas swirling around in his head, can answer that complex question with a simple sentence: “In modern America, there’s just enormous amounts of waste that contain tremendous value.”

And that’s the million-dollar message The Plant is trying to sell.