After nearly 40 years, Detroit’s Heidelberg Project is still confounding and educating visitors.

With your back to Detroit’s small Heidelberg St., it looks like the McDoughall-Hunt neighborhood is slowly being swallowed by nature again. Once a lively commuter neighborhood for auto workers, it now contains only a few livable houses. Others are abandoned and dilapidated. Some blocks are little more than grass.

When Tyree Guyton returned to the neighborhood it was in even worse shape. He grew up on Heidelberg St., but left in the late ‘70s for a stint in the army. When he came back, Heidelberg and the surrounding area were in outright decay. Families had moved out. Drugs had moved in. All that was left of the thriving neighborhood were remnants of their homes: toys, TVs, and miscellaneous items. Those became Guyton’s canvas.

Roughly 40 years later, the Heidelberg Project has cycled through more than a few titles: public eyesore, neighborhood curiosity, art installation, and tourist destination. A mix of found objects intentionally placed by Guyton and eye-catching houses covered in polkadots, clocks, and more, the block-long piece is whimsical and odd. It’s a twisted homage to a time when children used to play in the front yard and race home as the streetlights came on, but also a reflection of the abandoned needles and booze bottles that came later. It’s not the kind of art that you find on a wall in a gallery, or even on an Etsy shop. It’s the kind that commands you to stop and reflect on the fragility of neighborhoods, of cities, of our own lives.

The sign welcoming people to the Heidelberg Project is much like the project itself, constructed out of scraps scavenged from around the neighborhood. The two signs sporting the word “time” also set up one of the project’s major themes—how time can be manipulated, turned upside down, clocks turned backwards, in hopes of capturing something lost.

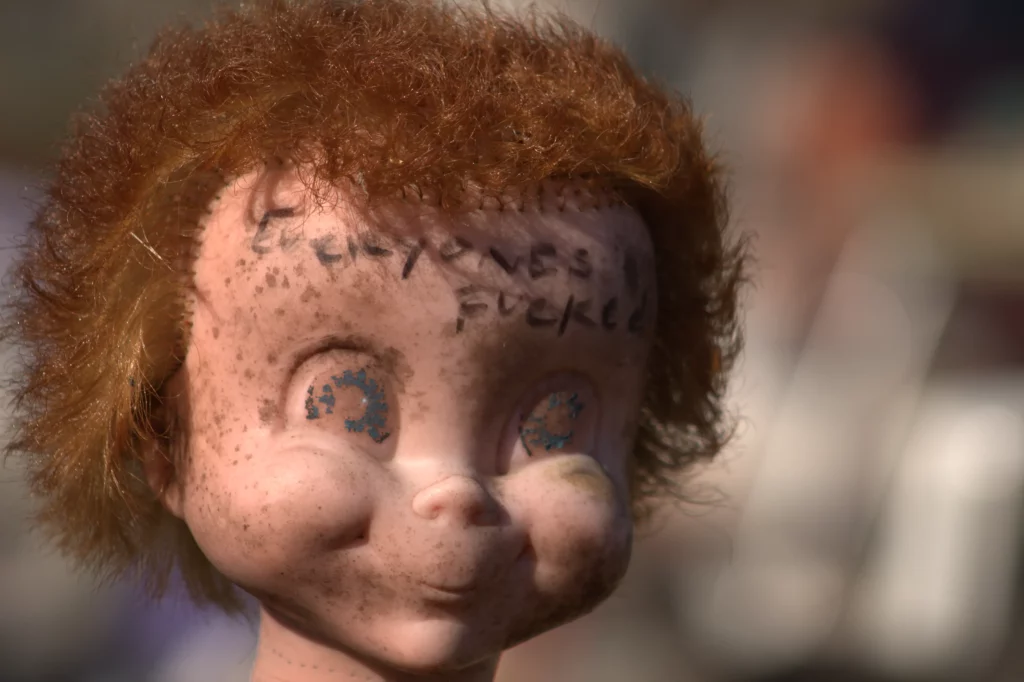

Dolls, perhaps hundreds of them, now aged and moldy, are scattered throughout the project. Some of them have been beheaded like this one on a bench. Others are intact but laid out naked. All of them are survivors, though. The dolls and their stuffed animal counterparts once had a home, an abandoned two-story once known as the Doll House, but an arsonist burned it down in 2014. It was the fifth art house to go up in flames that year.

Messages are written on many of the objects throughout the project. Some of them reflect the harsh reality the neighborhood once faced. That reality hasn’t changed much, despite a city program to buy up the abandoned houses throughout Detroit and bulldoze them. The city’s core has begun to recover, with development expanding outward. Heidelberg St., located a few minutes north of Detroit’s downtown, has yet to see any changes.

Part of Guyton’s original muse was the death of his three brothers, lost to the streets. His grandfather placed a paintbrush in one hand, and a broom in the other. Together, they cleaned the streets, taught children to paint, and then began to create art. The scars of loss show up throughout the Heidelberg Project, though.

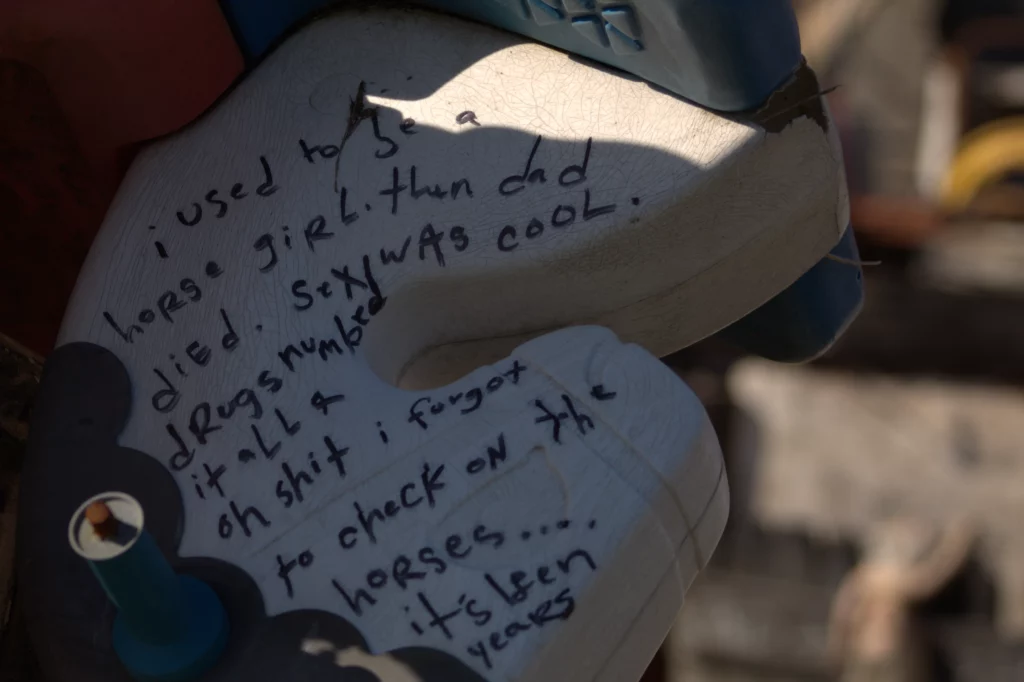

While it’s unknown if these words were written by the artist, a viewer, or a vandal, they feel as though they belong. These were written on a broken and faded hobby horse tucked among the greater Heidelberg detritus.

The city of Detroit has had a love/hate relationship with the Heidelberg Project. Twice the city has demolished some of its installations. In 1991, after appearing on an episode of the “Oprah Winfrey Show” where Guyton was confronted by a disgruntled neighbor, then-Mayor Coleman Young had three of the Heidelberg houses demolished. Eight years later, after Guyton launched numerous neighborhood-enrichment programs, the Detroit City Council again ordered the removal of three more houses. After twelve more houses burned during a string of arsons in 2013 and 2014, only a few remain, including the Polka Dot House, the Clock House, and the Number House.

Many installations throughout the Heidelberg Project often feel random, like someone forgot to grab a toy before they headed home for the night. But according to a 2019 New York Times article, Guyton methodically plans, sketches, and executes each piece. There’s intention behind everything, even these naked dolls seemingly abandoned on a cracking chair by the curb.

The news is fractured and siloed, some stories never migrating from one tribe to another. It left the country arguing over what even counts as the news, something Guyton captures in this section of the Heidelberg Project. As HP has grown up, its art has adapted to the times. What started as putting a boat on a house and an effort to put paint brushes in hands instead of guns has turned into activism and existentialism, reflecting on politics, AI, and racism.

Everything used to create the project has either been discarded or donated, including the hundreds of shoes that line a fence that separates two empty lots near the southern end of Heidelberg St.

The sidewalks on Heidelberg St. have become a part of the installation. There are polka dots and clocks painted on them throughout the neighborhood. Other pieces, like this commentary on the crippling nature of religion, find their way from the grass of the open lots to the concrete.

The Clock House is an ode to the inevitability of time. Collapsing slowly, shingle by shingle, it sums up the rot of the neighborhood. But the various time stamps painted on its side are reminders that time itself is just a construct, something people made up.

The view from the south side of the Heidelberg Project, where countless tourists have parked to wander down Heidelberg St. At one point HP was the third most-visited site in Detroit, welcoming over 200,000 people per year. Many still make the pilgrimage, including Guyton, who can often be seen walking the street including the day Urban Plains visited.

Guyton has risen to international acclaim, both for his work on The Heidelberg Project and for his other art. With gallery and museum shows across the U.S. and Europe, HP’s future has become unclear. Recent budget cuts led to layoffs at the organization. The project’s website even went down for a few days in April after the domain wasn’t renewed.