Just because you can’t see the illness, doesn’t mean it isn’t there

Words and Artwork by Kayla Parker

Video by Nadia Valentine

*Everything you see and hear in this video is portrayed by actors

I don’t know how it started. I don’t know why it’s there. I can’t tell if I’m going to get better or if I’m just going to keep trying one pill after another while the doctors play with my mind like a lab rat. Because it’s not a switch you can turn on and off.

If you look closely enough, there are signs, but you probably wouldn’t notice that I have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Most of the time, these things are hidden. You learn to hide your scars and your flaws, because that’s what humans do.

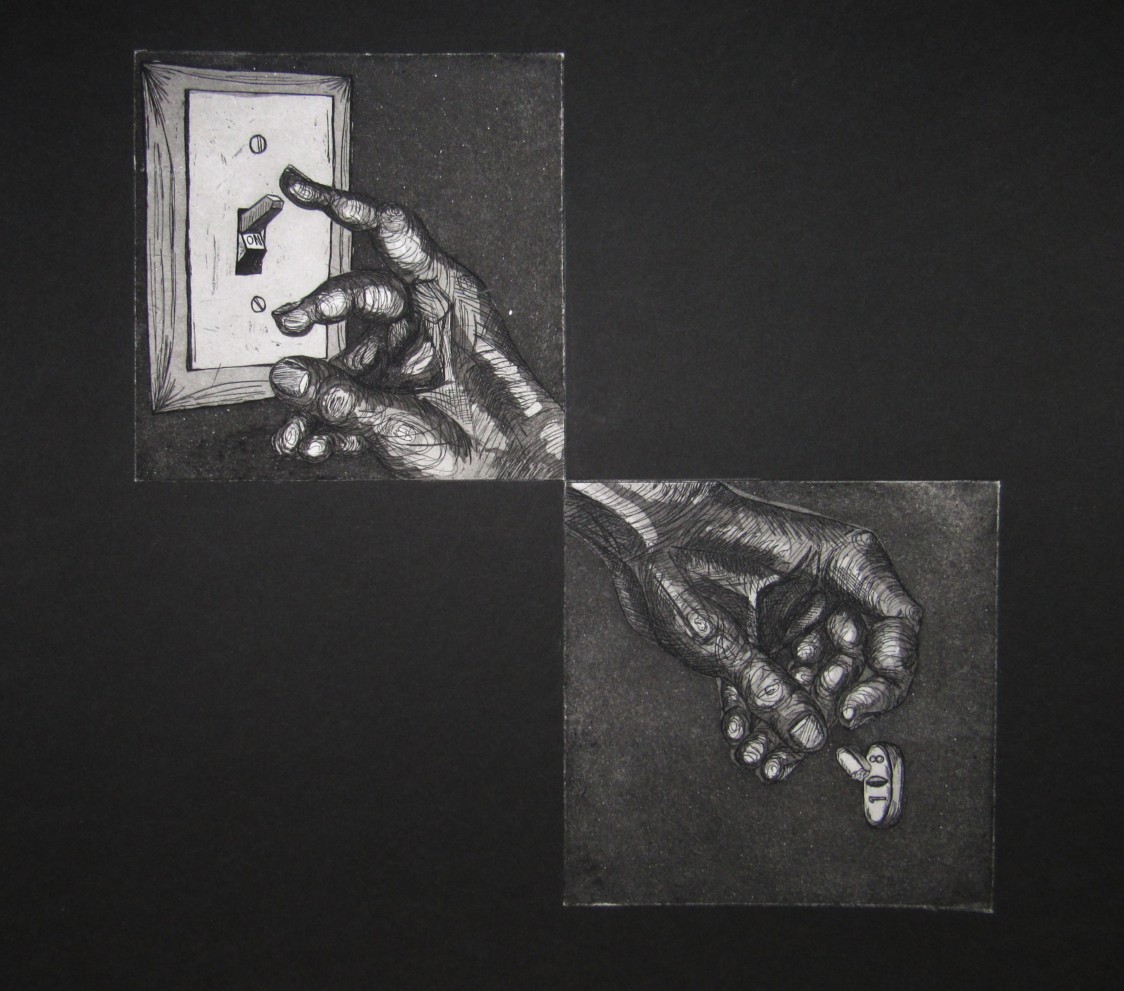

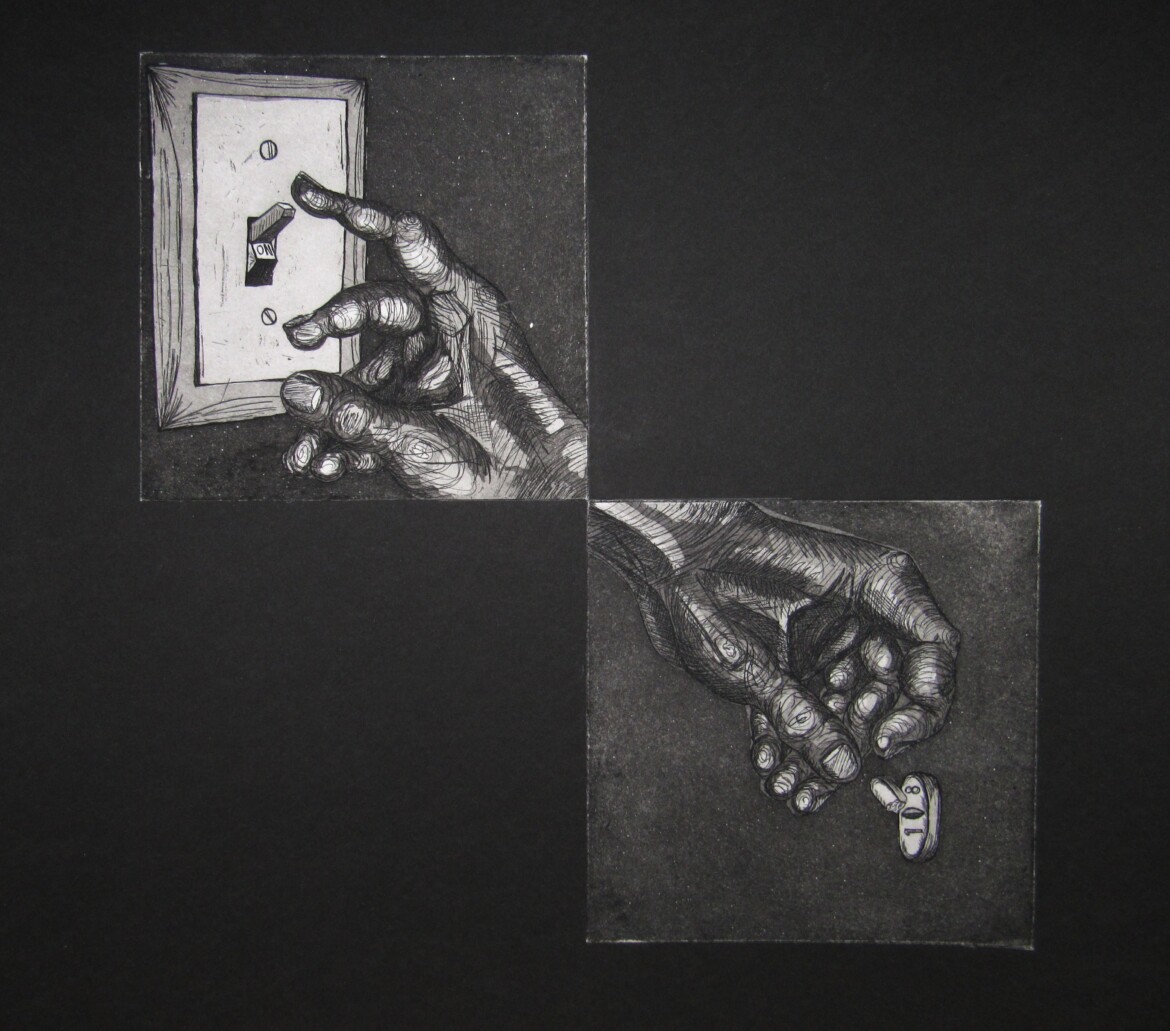

When I was a child, OCD appeared in more apparent ways. The handle of the sink needed to be touched six times, the right way, after washing my hands. The light switch needed to be touched repeatedly, usually in sets of threes. Hardly ever was it just one, two, three. I would start over, flip the light back on, and try again. One, two, three. Because simple things like turning off a light aren’t so simple with OCD. And medicine, though it can be a game-changer, is no magical cure. Sometimes things get worse. And taking a pill is like trying to turn off a light for me. It’s just a shot in the dark, hoping that this time, things will be “right.”

150 mg, Intaglio Print, Kayla Parker (Marple) 2016

I distinctly remember one of the first times I went to therapy, and I was going through the cliché phase of OCD where I washed my hands all the time (and that is not to minimize anyone who faces this aspect of OCD, it is just to acknowledge that this is a stereotype enforced by the media). In fact, I washed them so much that they bled. I washed them so much that it hurt to bend my fingers because another half-healed wound would break, and my hands would ache and be covered in blood again.

I was in high school at the time, and my mother was there with me. In front of the therapist, she said “Show her your hands.” And I remember prying my hands from beneath my thighs, and I felt like a freak show character. Come see the OCD girl. Come one, come all. I fit the bill of an OCD stereotype to a T.

So several years down the line, I forced myself to change my compulsions. If I needed to touch things, I was counting the items in my bag. Because I could just be searching for something in my purse, right? No one needed to know that I was counting every single item until I could breathe a little more easily.

More and more, the compulsions become thoughts in my head. I was afraid nearly every time I drove that I had run someone over. So I counted the cars as they passed, silently, if there was someone else in the car. When no one was looking, I’d check the bumper of my car for blood. The list goes on and on. My compulsions changed as I grew older, but the biggest thing was that they became more hidden. Because there’s no room for weakness in this world. And this world still views mental illness as a weakness.

I’ve hid my struggles for a long time, and I know many others do the same. I am one piece of this community that hides itself away. And I don’t think it should be hidden anymore.

Alienating Thoughts, Woodcut Print, Kayla Parker (Marple) 2016

Addressing the Issue

Andy Lange has also dealt with OCD throughout his life. “When I was a little kid, I remember I once put a piece of paper up my nose,” Lange said. “My dad had to get it out with tweezers. After that, I would always obsess about, ‘What if something goes up my nose and I have to go the doctor?’ My parents would be like, ‘What are you talking about?’” When he was 13, he had a panic attack and went to the ER. He couldn’t breathe. There, he was told that he had an anxiety disorder.

OCD used to be considered an anxiety disorder, but was recently reclassified to its own section in the latest Diagnostic Statistical Manual used by mental health professionals to diagnose mental illnesses. However, OCD still shares many characteristics with anxiety disorders.

Being diagnosed with a mental illness doesn’t mean that the disease exists in the brain in isolation. The brain is a physical part of the body, and the illness affects other physical systems as well.

For Lange, the symptoms began showing up as physical signs before the mental component arose. “Early on, it was just physical. I couldn’t really breathe,” Lange said. “Then, when I was 14, 15, 16, I started getting more concerned about things.

“I started going to therapy when I was maybe 16. At that time, I saw a therapist for a while in early high school. At that point, I was diagnosed with having generalized anxiety disorder.”

Prior to seeing his therapist, Lange sought out help from his family doctor. However, finding the right doctor who is knowledgeable in both what mental health looks like and how to treat it can be a challenge.

“My family doctor at the time was pretty old,” Lange said. “He didn’t seem very knowledgeable about mental health. I went to him one time. I was dealing with a lot of constant worry and dread and stress. He didn’t really give me much. He told me that I should go on medication. And I thought, ‘For what?’ He didn’t really diagnose me with anything.”

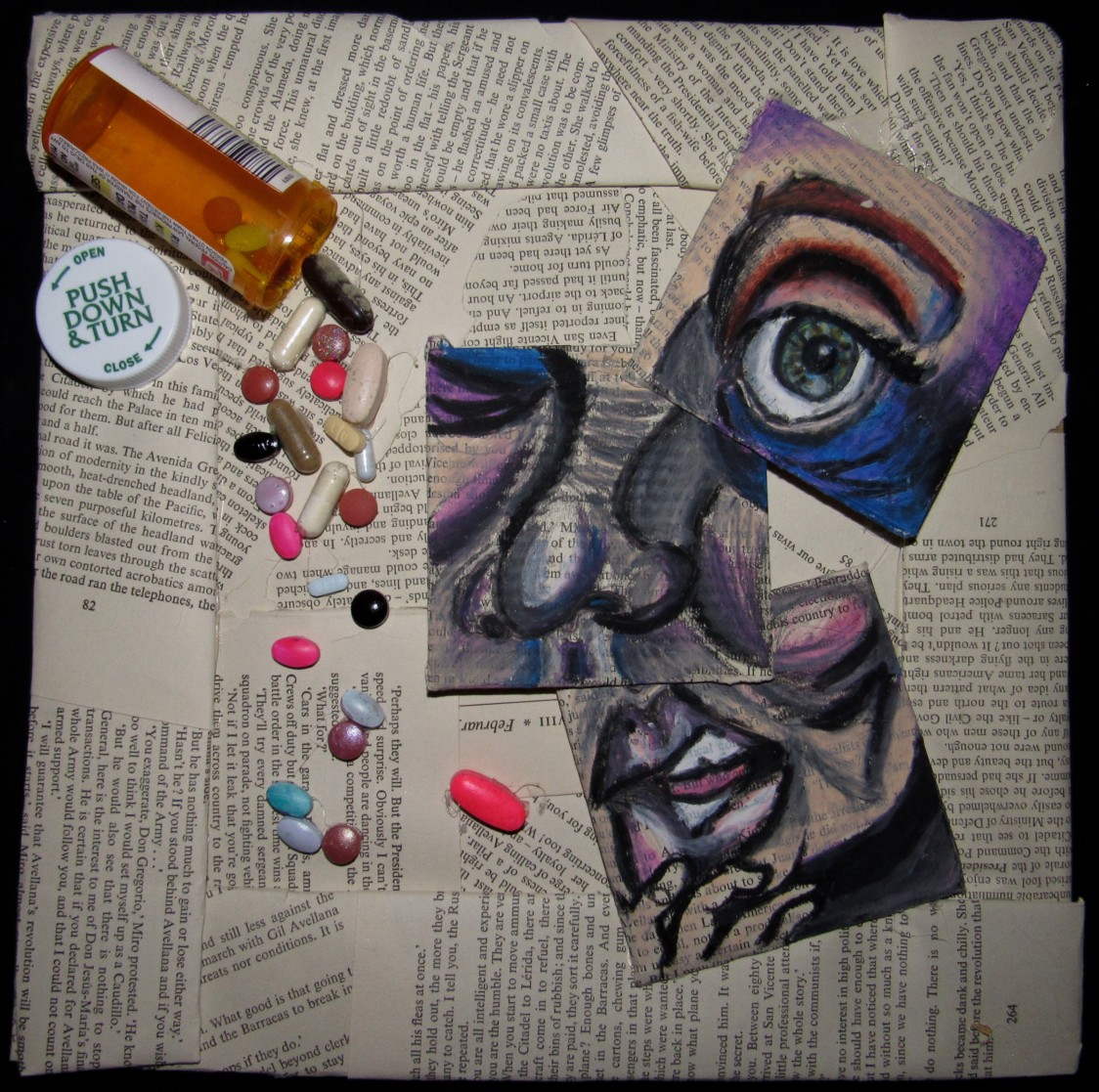

Candy Coated, Mixed Media, Kayla Parker (Marple) 2016

Diagnosis & Treatment

Lange finally looked up a local therapist. When Lange got there, he asked if the therapist thought he had OCD. The therapist told him he thought he was mainly just anxious.

Part of this may be because it’s not always easy to spy OCD when the symptoms are hidden. And with the version of OCD the media has enforced, it’s hard to know what it truly is and how it may be affecting someone.

Zach Pacha, a therapist who works for the Counseling Associates of Central Iowa, PC, knows what OCD looks like in real life. “The big problem with OCD is a person has these recurring thoughts,” Pacha said. “They don’t want them, they’re thoughts that they’d rather just not have, and they kind of keep going.”

Like a scratched record, these thoughts keep replaying themselves over and over again. There’s no way to switch them off, but that doesn’t mean we don’t try. However, often the actions we take to silence the noise only makes it louder.

“Obsessions, obviously, they come up, they come up, they come up, and we do everything we can to get them out of our head. The problem with that is every time we try to push them away, or do something to keep them away, they just keep coming back, and coming back, and coming back. And they also come back stronger and more intense. That’s the rut that people get stuck in.”

There are two big things that therapists focus on when treating OCD: thinking and behavior. There’s an exposure to obsessions and treatment of behaviors or responses that arise in these situations.

“There are a lot of hidden things that people don’t see,” Pacha said. “And when you’re working with someone, you have to do a really thorough examination with that person, and they have to be pretty honest with themselves about ‘What are things I’m doing that kind of make myself safer? Is it giving myself mental reassurance? Is it praying so that nothing bad happens, or so that nothing bad happens to anyone else?’”

When symptoms become more concealed, it takes courage and honesty to bring up the compulsions that are happening. I didn’t want to disclose everything that was going on in my mind when I was 17 years old, because I felt like it would only create more problems. My family doctors started giving me bottles of pills when I was in high school before I had any diagnosis. I did the whole therapy routine, but I was still having trouble. Eventually my doctors didn’t know what to do anymore by the time I was a sophomore in college. So I started seeing a psychiatrist. And I thought, maybe, just maybe, this would be the part where I get my mind “fixed.” So I could be normal. Healthy. Happy.

But it’s not that easy. More medications, more side effects — and I’m still dealing with, among a variety of issues, OCD. Having that label has helped me understand my mind, and understanding OCD has helped me realize ways that I can help myself get better.

Pacha said, “Diagnoses are really just a language for people to communicate about things in the medical field and healthcare. To the lay people, I think it matters very little.”

However, to certain people affected, having the right language to communicate what is happening inside is very important.

“The reason it was so difficult at first was because I didn’t know anything that was going on,” Lange said. “I felt like I was out of control because I didn’t really have a name for it.”

Hearing those words can be both a blessing and a curse. They’re something to cling to, something that helps explains what’s happening. However, as comforting as a label can be, there is the fear of a label consuming individuality.

“It got more specific as I got older, but just being told, ‘You have a condition. This is what it is.’ It just felt good to feel like this person understands me.” Lange said. “I think, in some ways, a label is good because you can identify with other people, and you feel like you know what’s going on it a lot of ways. But in other ways, you don’t want to define yourself by a label.”

People don’t always want to tell you what you have. I’ve had therapists say it’s more about providing treatment than labels, but I find comfort in being able to identify as having OCD, generalized anxiety disorder and a panic attack disorder. It’s not about throwing these terms around ⎯ for me, it was a powerful way to separate the person I am from the illnesses I have. When a therapist gave me an official diagnosis, and another affirmed it, I felt validated. I needed to know the enemy I was facing.

Lange said when he was 23 or 24 he was formally diagnosed with OCD.

“The more accurate diagnosis is I have OCD with agoraphobia and panic attacks,” Lange said.

Lange’s OCD has been strongly influenced by his struggle with panic attacks, from his first one at 13 to his time in college. “I think a lot of my OCD is about having panic attacks. In college, I remember having a panic attack one of the first days of class. So, after that, I kind of stressed out going to that room.

“I always wanted to sit by the door so I could get out of the room easier. I would just kind of obsess about all these little things. Then I might go to a different class that I hadn’t had a panic attack in, I would still be a little OCD about it, but I wouldn’t feel the same level. I think a lot of it is obsessing over how to prevent getting into situations where I feel trapped or have a panic attack.”

It’s easier to avoid situations where panic attacks are likely to occur than to face the issue head on. In fact, facing these situations can be terrifying.

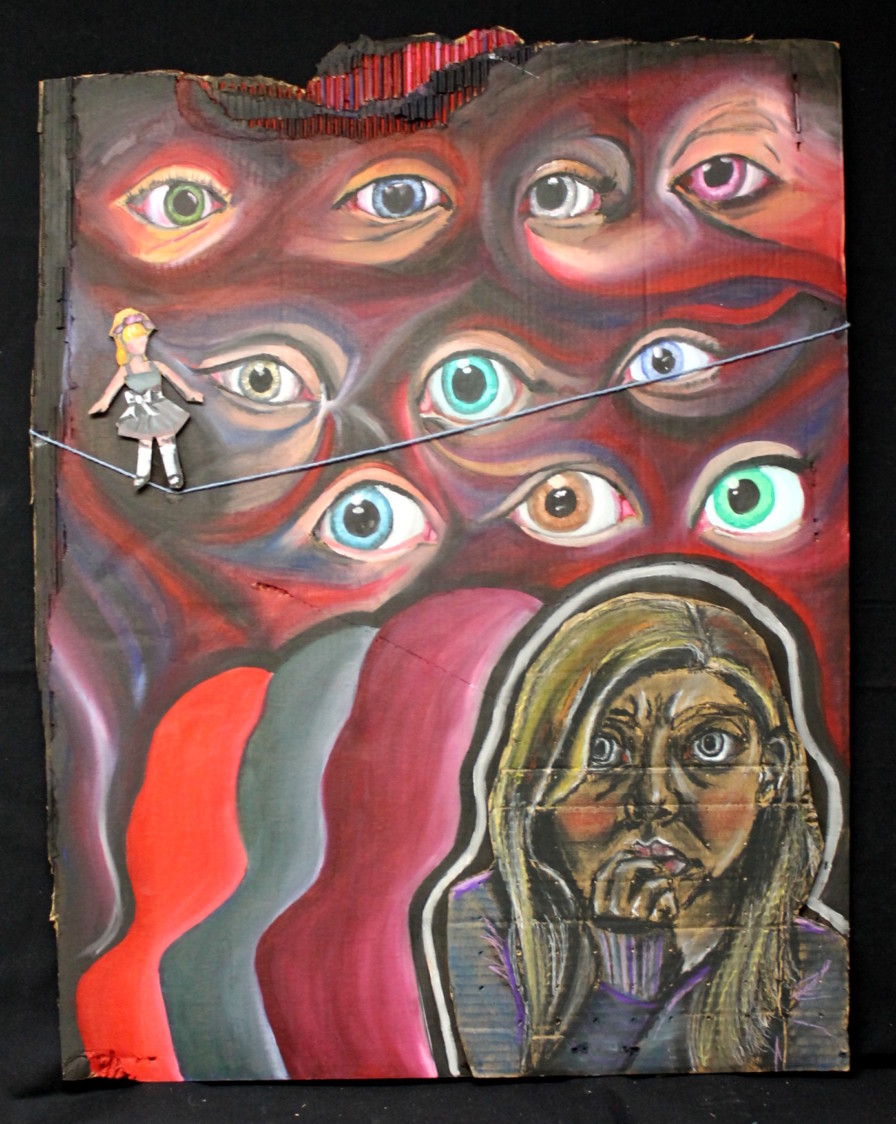

Insecurity: Anxiety, Mixed Media, Kayla Parker (Marple) 2014

Finding a Support System

“When I was going to my therapist I used to see, he asked me, ‘Do you think you deserve to be happy?’ or ‘Do you think you’re being kind to yourself?’” Lange said. “I found that really hard to answer. The hardest part has been not only trying to get better and to be less stressed and less anxious and less obsessive, it’s also been just like, ‘This is part of my life.’ Even when I am doing really well, there will probably be small bits of this that peek out. That’s okay. I think finding that level of acceptance is really important.”

This is part of the process of therapy, Pacha explained. It’s also part of being human.

“As humans, we’re probably going to do as much as we want to do until we feel okay,” he said. “We don’t always take doctor’s advice. I like the idea of losing weight, but I also like the idea of eating cookies. The problem with that is there is a good chance for a relapse.” But a relapse doesn’t mean that you’ll lose the progress you’ve made. It’s just a small step back from where you want to be.

“The idea when you start something is that you want to get to that 0 of 0 rituals,” Pacha continued. “Someone going from having to get reassurance for two hours a day, every single night, to they no longer have to even do that every single day? That’s a pretty big increase. Do they still have obsessions? Yes. Do they still do rituals? Yes, at times. But you have to look at their functioning and their quality of life too.”

This is important to consider. People with OCD have as many possibilities and opportunities as those living without the disorder. It just presents challenges in certain areas.

“People can still have jobs, they can still have relationships, people are definitely married,” Pacha said. “One of the common things that comes up is the couples work that you have to do in OCD, whether it’s a parent with a kid, or a spouse with the significant other that’s suffering. They’ll do things that might inadvertently keep the OCD going — you can call them accommodations. So you have to bring that person on board to help them.”

Lange’s girlfriend, Erin Austin, lives with him and helps out when he’s struggling. However, Austin struggles with anxiety and depression, which presents its own set of challenges. Together, they help each other out. It can be tough when they are both facing difficult days at the same time, but they make it work.

Lange explained that it’s about learning to see your thoughts as they come up and not letting them take you away. “Your thoughts are blowing up like a balloon floating by you,” Lange said. “You just grab onto it and you just follow it. You just grab onto this balloon, and it just takes you away. All of a sudden, you’re just rehashing these thoughts.”

Letting go of the balloon and the thoughts isn’t easy, but this visualization has helped Lange through his struggle with OCD. Austin also helps remind Lange to let go of the balloons, and this in turn helps him.

Austin said that with Lange, “He says, ‘I think I’m about to spiral.’ Then the next two days or three days, he’s more obsessive about things than usual. In terms of the “O” and the “C”, he’s a lot more “O”. He really doesn’t have a lot of compulsions. He just obsesses about a lot of things and wants to talk about them so much. Mostly physical health things. When he says, ‘I’m about to spiral,’ I know the next few days he’s going to take his temperature a bunch of times or ask me forty times if he should go to the emergency room because he has a funny feeling in his stomach.”

With Lange and many others who deal with OCD, compulsions aren’t always as visible. This is why OCD is easily hidden from others.

So what is the root cause of OCD? “We don’t know,” Pacha said. “It’s a cluster of things. We think it’s part genetic, we think it’s part learned behavior, we think it’s part personal experience, but we can definitively say we don’t know.

“I do know that it affects millions of people worldwide, and I don’t think that’s going to change anytime soon.”

So in the meantime, it’s about addressing the problem. Treating an illness, informing and educating the public, and encouraging those who suffer to get help when they need it or speak out when they’re ready.

“I always found it very empowering whenever I saw people in the media that identified as having an anxiety disorder,” Lange said.

Pacha also believes this is an important component of de-stigmatizing the illness. “Have there been improvements? And I can even say that from the last 10 years until now — yes, absolutely,” Pacha said. “And it starts with people coming forward, whether it’s actors, whether it’s people in the entertainment industry, sports people, politicians, continually to bring it up or talk about their struggles with it. It’s not something that’s just going to change overnight.”

He compared the fight for the acceptance of mental illnesses in society to the battle for civil rights or same-sex marriage. It has taken time. It will take time. After all, in the 1960s, healthcare professionals were still performing lobotomies — drilling holes in peoples’ brains.

“Anyone that thinks they might have OCD, to just know how much of a difference it makes when you reach out, get help, or decide if you want to try medication, or if you start talking to someone,” Lange said. “The difference in my quality of life since I’ve done that has been monumental.”

Individuals often find different methods that work for them. Therapy and medication are large components of treatment. However, it’s not a one size fits all solution, and oftentimes it’s not all that’s needed. For Lange, meditation and running have kept him moving forward in his recovery.

For myself, I’m still trying to find the answers. Oftentimes, creativity is a huge part of my healing process. If I can take the ugliness of this disease and turn it into something beautiful or at least intriguing, then I feel better. I feel like in some way, I’ve turned the bad into good.

Partly, that’s why I’m writing this, too. In the way that a paintbrush across the canvas starts to soothe the struggle in my mind, there’s a satisfying click of the laptop keys as I share my story, and the story of others struggling with OCD. It’s my way of taking the mess in my mind and hoping something beautiful will bloom.

Producers: Nadia Valentine & Kayla Parker

Actors: Haley Martin & Jacob McKay

Voiceovers: Haley Martin & Gerry Tetzlaff

Music: Hill “No More”

Thank you to Andy Lange for letting us interview him and use his responses for this video!

1 Comment

This is beautifully written and illustrated. Thank you for sharing your struggles, knowledge and heart Kayla.