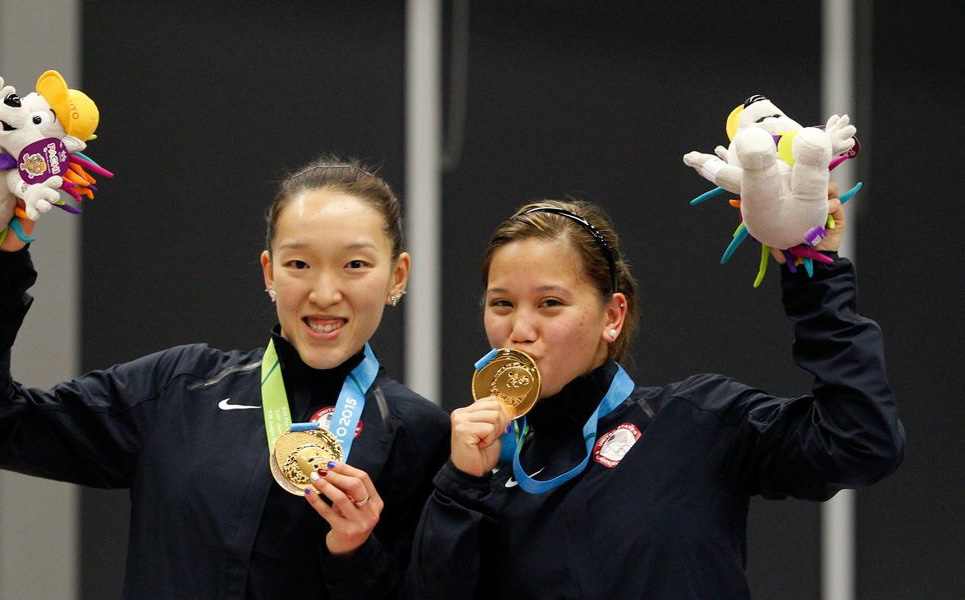

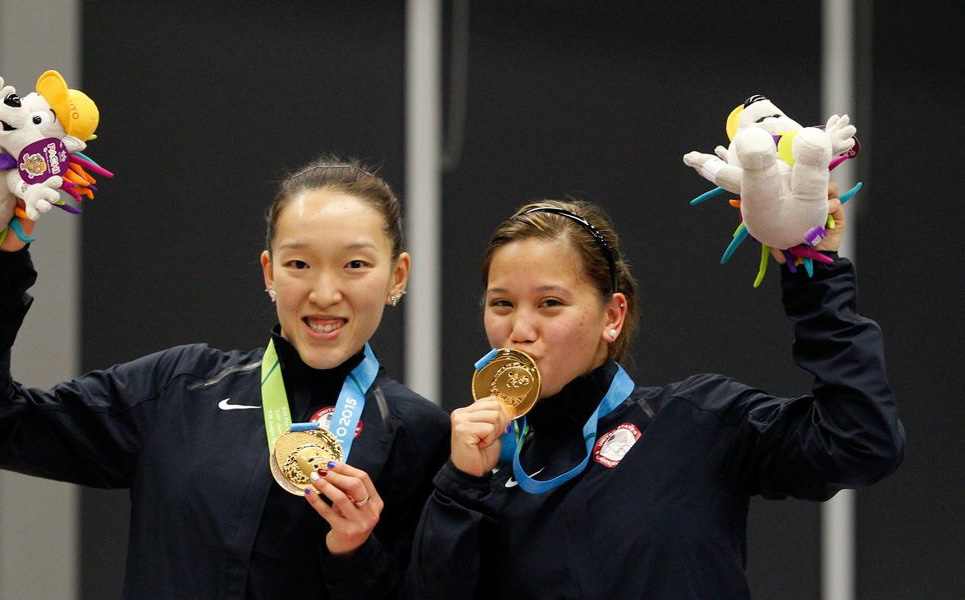

Minneapolis native Paula Lynn Obanana, right, and her women’s doubles partner Eva Lee won gold at the 2015 Pan American Games in Toronto. Photo courtesy of Roy Paras at EPX Elite Performance

The Olympic Games only last for two weeks, but for Team USA’s Paula Lynn Obanana, getting there is a daily feat

Words by Melissa Studach

Standing at 5-foot-3, Paula Lynn Obanana just reaches eye-level with the top of a badminton net. At the moment, though, she is significantly lower than that. She’s stretching in front of the mesh on the endless courts of the Los Angeles Badminton Club with her doubles partner Eva Lee.

The duo visits the facility every morning to practice rotations and strategy on the court. “I’m more of a power player, and Eva is more like a step-up player,” she says. “It’s a unique partnership, but it works well.”

Obanana wasn’t always a power player. Sure, she was hungry—just not necessarily for the game itself. “As funny as it may sound, it started with a sandwich,” Obanana says. She began playing in the Philippines, her native country. While waiting for her parents to pick her up after school, 10-year-old Obanana was offered a sandwich from the school’s athletic program if she’d give badminton a try. It didn’t take long for the coach to notice her potential.

Today, Obanana gets much more than free sandwiches for playing the sport. As a women’s doubles player on the U.S. Olympic Badminton Team, she’s playing for gold.

Change in Play

Obanana isn’t new to national attention. Just six months after she started playing the game, she qualified for the Philippine Junior Nationals Badminton Team. At her first tournament, she beat the four-time Nationals Champion. By age 13, she made the national team. “When you’re a badminton player in the Philippines, it’s like you’re an NBA or baseball player [in the U.S.],” she says. “You’re on TV, in magazines. It’s huge.”

But the attention she garnered competing internationally with the Philippine Olympic Badminton Team was impermanent. When her mother was offered a nursing job in the U.S., Obanana, then 20, decided to migrate with her parents. The family settled in Minneapolis, where a term like shuttlecock, the projectile hit back and forth in a badminton game, only resulted in confused stares.

Obanana’s American badminton career seemed hopeless. She picked up jobs at Abercrombie & Fitch, cooked meals at a local Presbyterian home and worked the night shift back-stacking at Target. “It was really normal. Work and then home,” Obanana says. “It was challenging for me because of the world I had in the Philippines.”

When you’re really an athlete, you know the spirit and feeling to be an athlete. I didn’t know at that time if I could still make it, but I never give up.”

– Paula Lynn Obanana

Normal didn’t last long, though, thanks to a call from California.

A friend of Obanana’s who’d recently moved to San Francisco for college told her that badminton was prevalent in the city and encouraged her to look into it.

Obanana, who had been living badminton-free in Minneapolis for two years, was intrigued by the proposition. “I was trying to figure out if I still wanted to play,” says Obanana, who had already undergone two knee surgeries. “But when you’re an athlete, you know the spirit of an athlete. I didn’t know if I could still make it, but I never give up.”

Upon making the move to San Francisco, Obanana was hired as a coach for the U.S. Junior Nationals Badminton Team. It was at a tournament in 2010 where she first saw her future teammate, Eva Lee, competing. What began as a friendly singles match-up turned into a doubles competition against the boys. “And then we beat the boys,” Obanana says nonchalantly. A partnership was born.

Getting to the Games

The strength the partners have goes far beyond what can be gained on a court. Aside from a few coaching gigs here and there, Lee and Obanana don’t have time to work outside their daily training schedule. The occasional sponsorships helped, but Obanana has had to rely on her parents’ support to continue playing badminton full-time. When the Brazil-based Olympics started looking like a possibility, the partners created a Go Fund Me page to make getting there more affordable.

With money as tight as it is, Obanana and Lee have to compete without a coach—an uncommon move in the women’s doubles competition. “When I look back, it’s amazing. We actually did it us two,” she says. “Others have all the resources to motivate them, but we were struggling in every aspect. Yet we were the ones who kept winning.”

The more struggles that we encounter, the more we’re winning.”

-Paula Lynn Obanana

And win they did. In their first year as partners, Obanana and Lee took home gold in the Brazil International Badminton Cup and silver in the Boston Open Badminton Championships. In 2011, they medaled in seven international tournaments. They were a shoo-in for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London until an administrative error put a halt on their dreams.

Their badminton association forgot to enter the women’s double team into an Olympic-qualifying tournament. Even though the pair was ranked number one in the world, it was Canada that went to the Olympics. Twenty-seven-year-old Obanana was devastated. “That was heartbreaking, especially for me,” she says. “My partner had gone to the 2008 Olympics, but it was supposed to be my first. We got stronger, mentally tougher. And through all of that, we can apply it in the next stage.”

That stage was in Rio. Obanana and Lee qualified for the 2016 Olympics. Although they lost in the preliminary round to South Korea, Denmark and China—definitely not the results they wanted or were expecting—they brought the same passion to the court as they did when they beat the boys during the first match they played together. The same hunger that got Obanana into the game. The same drive she brings to practice every day.

Match Point

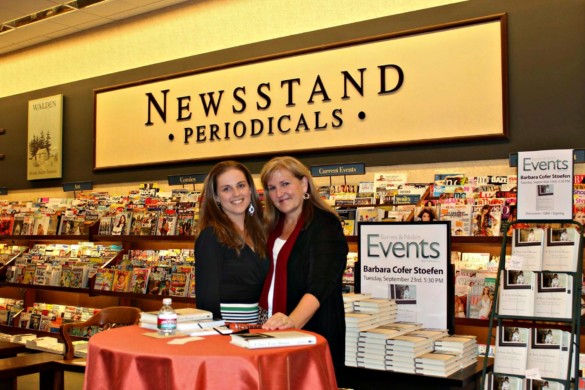

After a two-hour drive—“You know how LA traffic is,” Obanana groans—she reaches EPX Elite Performance in Woodland Hills, California. One thing that’s even more unpredictable than the city’s traffic: Obanana’s future. Although fans are hopeful the pair will make it to the 2020 games, Obanana and Lee don’t live by the 4-year Olympic plan. “Me and Eva, we take it slow,” she says. “One tournament at a time.”

With a tournament coming up in November, they’ve got workouts to focus on. Exercise balls, kettlebells and equipment mats line the back wall of the no-frills EPX gym. Here, the focus is on strength training and conditioning.

“Badminton is physically demanding. You have to develop power, speed and agility,” she says. “Once you have that, it’s easy to be on the court.”

The rigorous training can be demanding. Two-a-day practices six times a week can lead to a point of breakdown, Obanana admits. It was similar to her arrival to the U.S., back when she moved to Minneapolis and didn’t own a car. After working the night shift at Target, she’d have to walk the 45-minute route home.

“That was one of my motivations,” she says. “When I thought I couldn’t train anymore—when my best still wasn’t enough—I thought if I walked home from Target in the cold and snow, I could do this.”

Obanana may be from the Philippines and based in California, but it’s the resilient Midwest spirit that keeps her going.