Everything you need to know about quidditch and its journey from fantasy to for-real

Words by Taylor Eisenhauer

Video by Alex Payne and Allison Trebacz

Audio by Jessica DiDominick

Photos by Allison Trebacz

Graphics by Emily VanSchmus

The players fly down the pitch as four balls—for now—hurl through the air. One of those balls can be used to score. The fifth ball, also used to score, comes into play later, while the remaining three exist solely to hit other players—and hit them hard. They’re called bludgers for a reason—glorified dodgeballs designed to disrupt, distract and not quite decimate players.

At the moment they are flying all around, trying to stop the player with the scoring ball—the quaffle—as they sprint toward the three rings at the end of the pitch. If they get the quaffle through one of those rings, it’s 10 points. So they need to be stopped. They dip and dodge and keep hustling forward, holding their broomstick—a 4-foot-long yellow pipe between their legs. The action moves all around them. Then, out of nowhere, it hits them full force from the side and knocks them to the ground. It wasn’t a bludger. It was another player delivering a serious body check—and providing further proof that this isn’t Quidditch: the magical sport from your favorite childhood books. This is quidditch: the rugby-reminiscent, bring-you-to-your-knees full contact sport.

Starting in 2005 at Middlebury College in Middlebury, Vermont, IRL quidditch has become an entity all its own, separate from Harry Potter. That doesn’t mean players aren’t fans—they just don’t have to be. The draw is the newness, the competitiveness, the inclusivity. In 2005, quidditch was very much a fan’s game. But now, in 2016, it’s a full-contact sport with its own agenda—one that might leave you a bit bloody and bruised.

The Basics

Harry Potter aficionados might find the game familiar: one seeker, three chasers, two beaters, one keeper and five balls. And don’t forget the three hoops used on either end of the pitch. Think of them like soccer goals: the ball goes in, and points get scored. Of course, there’s more to it than that. There always is.

A complete overview of USQ regulations can be found in the official rulebook.

But when you’re adapting a fictional sport into a real one, some changes need to be made. Mary Kimball, the events director for U.S. Quidditch, the sport’s national governing body, explains the three major differences. “The first is, obviously, we don’t fly,” she said, laughing. “The beaters, who can throw bludgers at players, have to throw [them] with their hands. They do not get bats. The third major difference is the snitch.”

If you know anything about the Snitch—small, golden, flies around like an indecisive hummingbird—well, forget it. This is a whole new ball game. Yes, the Snitch still ends the games, and yes, seekers still desperately want to be the first to catch it, but the similarities stop there. The real-life snitch is only worth 30 points, which is significantly less than in the world of Harry Potter. “The snitch is worth 150 points in the book, which, if you’re trying to play a sport, means that in real life no one else in the sport matters,” Kimball said. “That’s not fun for a sport.”

But a neutral player—designated from a team not competing in that match—with a ball attached to the waistband of their pants, going hog-wild? Now that’s fun. “They are solely there to be the snitch runner,” Kimball said. “They are a neutral athlete. And they are not affiliated with either team.”

But they can’t get too crazy. Unlike days of old, they can’t run all over a college campus. They have to stay on the pitch.

The Snitch runner stays on the sidelines until 18 minutes into the game to give each team time to score before the Snitch is caught—because that ends the game. But catching the Snitch in the real world is a little less graceful than it is at Hogwarts: The Snitch is pulled from the runner’s waistband, often resulting in tackle scenes straight out of The Waterboy. If they’re lucky, those Snitch runners don’t get stitches in the process.

And where there are snitches, there are brooms. Broomsticks are part of the game, but USQ has gone bristle-less—see the aforementioned 4-foot yellow pipe—which players like Daniel Shapiro, a grad student at the University of Missouri, appreciate. “A lot of people would look like their thighs got in fights with a cat,” Shapiro said.

Players from the University of Minnesota and the University of Missouri wait for the game to resume at the Midwest Regional Championship in Nevada, Iowa.

But while brooms remain, the grand wooden stadium made famous in the Harry Potter movies does not. Instead, the quidditch game space looks more like your typical soccer field, such as the one found at the SCORE Pavilion in Nevada, Iowa, which isn’t very grandiose. It’s really not even grand. But it is functional. Baseball diamonds, playground equipment and soccer fields compose the recreation complex—a perfect setting for the mad rush of players pummeling each other.

Beyond Its Origins

Quidditch’s biggest challenge in growing into a mainstream sport with its own identity is separating itself from its magical beginnings. “We are a sport first. Yes, the sport is adopted from the Harry Potter novels, but what we’ve done with it is really something—we’ve taken it much further than its roots, I think,” Kimball said. “We’re proud of where we came from, but like a lot of other things that have come out of the Harry Potter world, we are so much more than where we started.”

The effort to make this happen included more professional branding and attracting serious athletes. “Now, because there’s more of a competitive structure, and we’ve really done a lot in the last year to change our own messaging and be a sport first,” Kimball said, “you’re finding more and more athletes who are coming to quidditch, not because they’re Harry Potter fans, but because they’ve played other sports before, and they’re looking for something new.”

Minnesota players show their team spirit between games.

And that’s exactly why Rachel Heald started playing. Once her brother introduced her to the sport, she was sold. “It’s very strategic,” Heald said. “But it’s [also] really physical, so it’s really challenged me, and I know it probably challenges other females to go out there and hit guys. And you can!”

Heald, a sophomore at the University of Kansas, plays for the school’s club quidditch team and serves as its co-captain. She and her team competed at the Midwest Regional Championship, hosted by USQ, in Nevada, Iowa, which drew participants from all around the Midwest, also including teams from Illinois, Minnesota and Missouri.

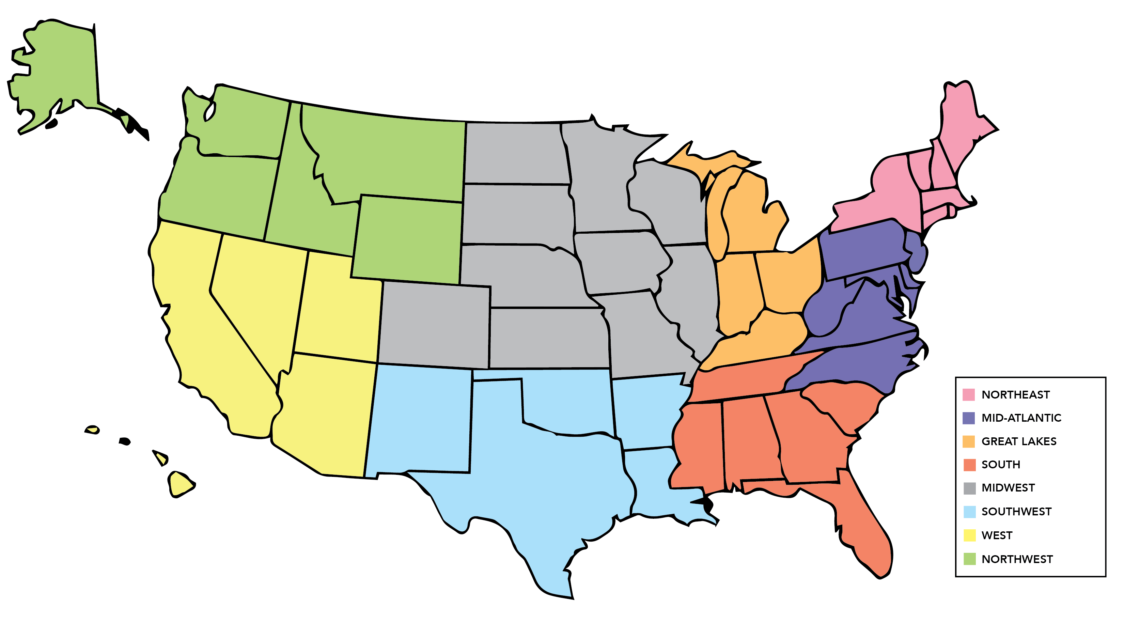

U.S. Quidditch recognizes eight regions and hosts a championship tournament for each one.

USQ hosts nine events throughout the year: eight regional championships and one national championship, held in April every year. All of the teams in the Midwest tournament are competing for a chance at nationals, which will be in Kissimmee, Florida, next spring. Those teams fall into one of three categories: high school youth, adult community and college. Kimball estimates that two-thirds of the teams are collegiate teams and the last third belongs to the adult community.

Shapiro, also a collegiate player for Mizzou’s club team, has been playing quidditch for six years and has only seen the athleticism grow during that time. “It is legitimately an athletic sport,” he said. “It’d be like if rugby, basketball and dodgeball had a weird night, and then there was a baby. That’s quidditch.”

But despite the seriousness of the sport, quidditch still appeals to fans of the fantasy in Harry Potter. So when John Olsen of Ankeny, Iowa, heard about the tournament, he made plans to attend. “My kid’s into Harry Potter, so when I read about it two months ago in The Des Moines Register, I’m like, ‘Oh my god,’” he said.

Olsen, who had never watched quidditch before then, was surprised by the sport’s physicality. “It can be a brutal sport,” he said. “I’ve seen some nasty hits and tackles, and there’s definitely a sense of rugby. I’m surprised there aren’t more injuries.”

But he was also struck by how tight knit the players seemed to be. “The teams are really close—just one big happy family,” he said. Olsen and his son even started integrating themselves into the community by making friends with—and later cheering on—the KU team.

So while many people are drawn to the sport because of Harry Potter, and others are attracted by the newness, they stay for what Olsen astutely noticed: the community.

Catching a Community

Camaraderie is not synonymous with quidditch—but it is a driving force of the sport. “You have to be tight-knit when you’re planning a new sport like this,” Kimball said. “They all care very deeply about the sport. They form very deep team bonds.”

Heald knows that feeling well—despite how brutal the games can be. “You play your heart out and you’re hitting people, people are getting injured, and after the game, you could be best friends with the other team,” Heald said. “I have friends all around the nation because of this game. It’s really awesome.”

A member of Rachel Heald’s University of Kansas team (blue) runs down the pitch with the quaffle.

But even more than that, the community is one that actively encourages inclusivity, something that sets quidditch apart from other sports—in the best way possible. “All genders compete together in quidditch,” Kimball said, “And what that means is that the dynamic on the pitch is going to be just as intense as other sports, but you’re going to see a much wider variety of representation than you normally see in traditional contact sports.”

Quidditch is considered a mixed gender sport and has a “gender rule”—a maximum of four people from one team who identify with the same gender may be on the pitch at the same time. “Outside of that, we don’t require people to state their gender, and we are just here to provide a space for all athletes to compete together,” Kimball said. “Not only is [quidditch] mixed gender, but it doesn’t ask questions about gender.”

Like the books from which it originates, quidditch brings people together: Players. Fans. Everyone. Heald says her quidditch cohorts are some of the best people she’s met. “Everyone’s so genuine,” she said. “They obviously don’t really care about outward appearances. We’re out here playing a ‘nerd sport.’”

Olsen and his son ended up staying through the championship game because they’d made friends with the KU team. “We sat down and started talking to two of [the players],” Olsen said. “So we have to stay until the bitter end.”

Kimball notes that the community make-up has changed quite a bit over the last several years. The draw was initially Harry Potter—and the novelty—but as the nature of the sport has grown, so have its followers. “I came for the Harry Potter,” Kimball said, “but I stayed for the competitiveness and the values that define the sport worldwide.”