In the spring of 1917, Kansas passed the infamous Chapter 205. This new law gave the State Board of Health the power to quarantine people. Only, this wasn’t the ‘stay at home and pick up a new hobby’ type of quarantine. It meant locking people up — often against their will. When Chapter 205 collided with World War I, it led to a domino effect that continued to impact women until 1956.

Nicole Perry, author of Policing Sex in the Sunflower State: The Story of the Kansas State Industrial Farm for Women, summarized the connection between Chapter 205 and WWI with a single word: men.

The US needed men to fight in the war. But during health checks, many were found to have syphilis or gonorrhea, disqualifying them from active duty. In reaction, the State Board of Health used the ambiguous nature of Chapter 205 to detain people who had (or were believed to have had) sexually transmitted infections (STIs). But it was the women who ended up being sent to a farm.

Carrying Out the Law

Another thing Chapter 205 failed to specify was the way that women would be arrested. Sometimes, a woman would go to her doctor to receive treatment for an STI. Instead of getting help, she’d be reported to the police, arrested and sent to the Kansas State Industrial Farm where she would receive treatment (along with a prison sentence). Some women — around 20%, according to Perry’s research — went to the farm voluntarily because it was the only way they could receive medical care. Others were turned in by the husbands who likely gave them the STI in the first place. And others, as documented by the Lansing Historical Society and Museum, were diagnosed based on “social criteria,” since actual testing for STIs was unreliable at the time. Said “social criteria” included whether they had been to a dance hall recently or had even just been seen out with a man.

They saw it as a moral failure of the women who had these diseases.

Nicole Perry

After a woman was arrested she often received an indeterminate sentence of 30 days to six months.

“There was a public health issue, but they were applying the solution of the prison system,” Perry said.

Why the drastic solution? They needed the men to be soldiers, and it was assumed that arresting women would stop the spread.

“This is a disease that most of the women were contracting through heterosexual sexual relationships,” Perry said. “It really didn’t make any sense, from a logic perspective, that you would only focus on the women and not the men. They saw it as a moral failure of the women who had these diseases, even though many of them were married.”

Other reasons were steeped deeply in social movements of the time including eugenics, racial purity and feminism.

Kansas had an active women’s activist group around this time. At the time there was no women’s prison, only a woman’s ward at the Kansas State Penitentiary which also housed men. The women’s activist group lobbied to have a women’s prison created separately from the penitentiary. They were successful. The women were moved to a farmhouse away from the penitentiary grounds. Eventually, the farmhouse was officially established as the Kansas Industrial Farm for Women.

The farm wasn’t like the penitentiary; rather, the women there worked on the farm and stayed in cottages where they learned other skills and lessons deemed necessary by the state. This may not sound like the worst prison sentence to serve. But it’s important to recognize the wider implications of the farm by looking at who the women in the activist group were.

“They were the upper-class white women who were going to be in charge of helping all the other groups of women in the state ‘evolve,’” Perry said.

The majority of the women at the farm were poor and often women of color. Part of the motivation behind the prison and Chapter 205 was to limit their chance of having children as the influence of eugenics spread.

Lasting Effects of Intrusion

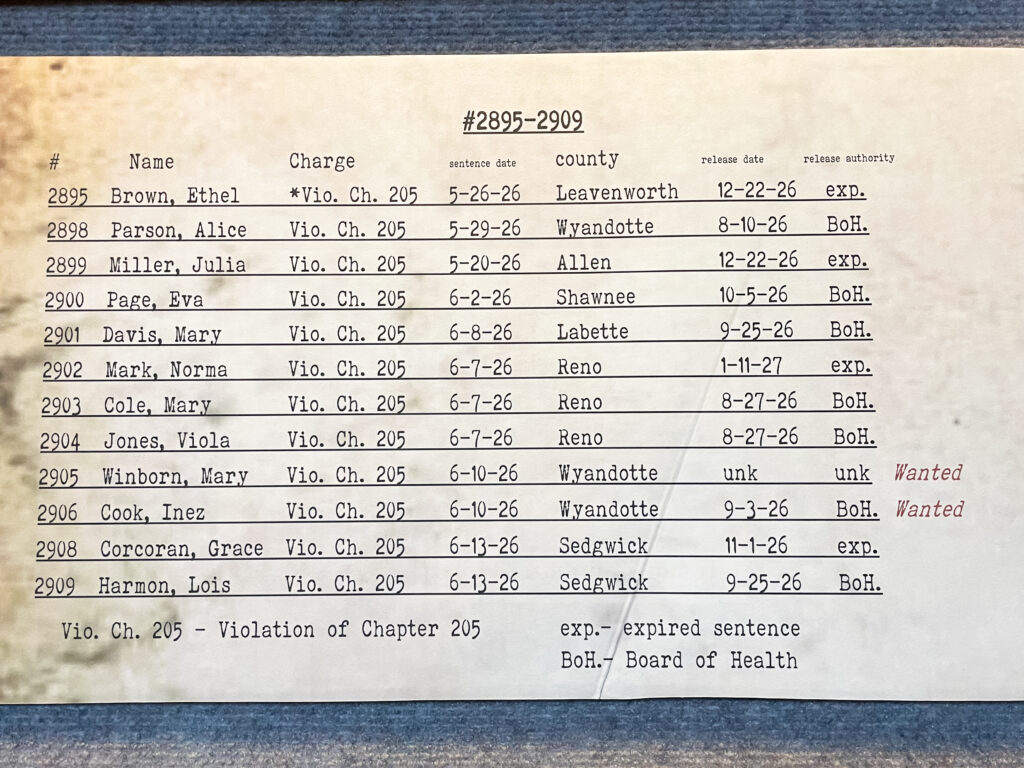

Between the years of 1918 and 1942, over 5,000 women and girls were detained under Chapter 205. However, Perry found records of Chapter 205 being enforced as late as 1955. Those women and girls were treated as “prisoners first and patients second.” The law itself marked “a broader growth in government intrusion into citizens’ sex lives in the United States, particularly for women, racial minorities, and the poor,” Perry wrote in the conclusion of her book.

“One important takeaway from this was that the official state version of the social problem was very different than what the problem was when you actually listened to the people who were most affected by this,” Perry said. “The entire state approach was based on their understanding of these women and not actually listening to these women.”

Regardless of its faults, Perry believes the institution did a lot of good.

“These women had access to healthcare they wouldn’t have had otherwise. They had access to some job training,” Perry said. “But if they listened to the women, they could have designed systems that would have allowed women access to those same resources without being imprisoned. There was no reason why you couldn’t have free health clinics and job training and access to food and shelter in ways that would have been less expensive to the state and would have been able to, you know, respect women’s freedom.”

Learning From History

As someone who has spent ample time studying the farm, Perry finds it important to remember that these moments in history cannot be boiled down to black and white — and they shouldn’t be.

For example, Perry cites the contradictions within the actions of the women’s activist groups. On one hand, thanks to their efforts women earned the right to vote in the state of Kansas. On the other hand, it was those same activist groups who supported Chapter 205 and the farm which disproportionately affected women different from them.

“They weren’t reflective of their own privileges and they didn’t do a great job of listening to the women themselves about what they needed. So they weren’t always doing it in a real sense of trying to give agency to those women,” said Perry. “They were more trying to tell the women how to live their lives.”

Another notable conundrum was the hypocrisy of the farm itself.

“It doesn’t make any logical sense that you would imprison women and not men and that you would send women to prison for something that they didn’t really need to be imprisoned for,” Perry said.

It’s easy to want to believe there was just one bad guy behind the mass imprisonment of women. But there wasn’t.

“When you actually look at how it was implemented, it was like hundreds of people over like two decades who were involved with it,” Perry said.

The Kansas Women’s Industrial Farm and Chapter 205 seem to still be echoing in today’s society from the overturn of Roe v. Wade and states’ shifting laws on abortion to how addiction is handled. But that doesn’t mean there’s no time left to learn from them.

“To me it’s like looking into these kinds of contradictions,” Perry said. “Where did people think they were doing a good thing? And what went wrong? Those are the kinds of questions that I think if we really press into and then reflect on our own actions, it can lead to learning and change with what we do right now.”