Graphic by Kylee Bateman

Political polarization is a phrase that’s become common in political conversations. People are more polarized than ever, so the conversation goes. Every hot-button issue and even everyday problems seem to have two teams on either side, like abortion, healthcare, gun-control and government spending. But how did we get here?

Which came first? Polarized voters or polarized politicians?

“That’s a really big question in political science right now that we don’t necessarily have a good answer to,” says Brianna Smith, a political science PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota. “There’s a lot of research that suggests the more conservative an electorate, the more conservative of a politician they’re going to elect.”

Similarly, Smith says, urban cities in Minnesota have become more liberal, and they tend to elect more liberal city council members.

“There’s a benefit to you being more liberal than the last politician who got elected,” she says. “And that can be driving politicians to be liberal or conservative because the electorate is more liberal and conservative.”

Dr. Rachel Paine Caufield, who teaches political science at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, believes candidates and representatives are appealing more to the extremists in either party, leaving voters with fewer moderate candidates.

“Members don’t have to worry about listening to the other side or representing both sides,” Paine Caufield says. “They just have to think about representing one side, which pushes them to the edge. The biggest threat to a member of Congress is going to come from someone who’s more extreme but within their same party…that leads them to behave in more extreme ways. There has been some division among average Americans, but I think that’s being led by our elites, rather than the other way around.”

In short, representatives and candidates don’t have to appeal to the middle as much anymore. Paine Caufield adds that people are better at determining which party represents them best. And since people with similar ideas, values, and beliefs are moving closer to each other, it becomes easy for candidates to ignore the other side. That causes people to do the same.

“Polarization is explained through ‘sorting,’ the idea that people are increasingly geographically sorting into like minded enclaves of people,” Paine Caufield says. “But (they’re) also ideologically sorting very efficiently. Conservatives are very likely to be in the Republican Party; (liberals) are very likely to be in the Democratic Party.”

A quick glance at a map demonstrates this sorting. Most counties in the U.S. either voted overwhelmingly Democratic or overwhelmingly Republican in the 2016 general election (those are the dark red or dark blue counties). People living in those counties hold very similar stances and beliefs and showed it at the polls.

Social Media: bouncing our opinions back at us

“We are increasingly ensconced in our little echo chambers online, in our news consumption,” Paine Caufield says. “If you only hear one side and you think the other side is extreme and wrong all the time, if that’s your political discourse…then it’s not a surprise that voters start to inch out and become more polarized.”

Echo chambers or social media bubbles are another buzzword in the political realm today.

“People are withdrawing into these bubbles…” Smith says. “If you always like posts by your liberal friends and ignore posts by your conservative friends, you’re going to slowly build up this bubble of political opinions that are all liberal, and that’s going to make you liberal because all the information you’re getting is more liberal. And if you’re explicitly blocking people because you’re having political arguments with them and you don’t like it, that’s also going to reduce the diversity of your political network.”

Paine Caufield, who has been teaching political science for over a decade, says modern media consumption and the current media environment plays a major role in polarization.

“People are withdrawing into these bubbles…”

“In an era with very few news sources and more of a genteel civil discourse, it used to be that everyone was working with the same general storylines about current events,” Paine Caufield says. “And increasingly as our media environment has fragmented and fractured, and as particularly social media has allowed us to communicate quickly and communicate in ways that incentivise alarmism and provocative, outrageous statements…we’ve become much less concerned about creating opportunities for genuine disagreement.”

The psychology behind polarization

Smith says there’s a basic psychological reason why people try to push out information or views that contradict their own.

“There’s this thing called motivated reasoning,” she says. “One of your motivations could be accuracy, so you might want to have the most accurate information you can have. And the other motivation is directional. So you already have an opinion in mind and you want to keep that opinion and refuse all changes.”

When we hear or read information that proves us wrong, Smith says we get uncomfortable.

“We really don’t like the idea that we might be wrong. We also don’t like the idea that we might have to change our minds.”

This leads people to try to discredit the new information. And in an era of social media, fake news, and infinite amounts of information, it can get messy quickly.

“(Fake news) gives people a really easy way to get out of arguments without changing their minds,” Smith says. “So if somebody says to you, ‘This is wrong. I have a Snopes article on it.’ And you can turn around and say, ‘I have this different article from a different source that says I’m right,’ there’s a lot of time that has to be spent discrediting each new piece of news, which may either be completely fabricated or just misinterpreted. But every time you have a new source, it doesn’t matter if a source is a good source or not, so much as, ‘I have a new piece of information that supports me and therefore I am still right. Even if you have all this other information that say I’m wrong.’”

In addition to this motivated reasoning, Paine Caufield says she had the chance to talk to people and solicit feedback about how they felt about the current political environment and about the 2016 election results.

“There’s this real sense of anticipatory threat that I hear, that people are sort of hunkered down waiting for the worst possible scenario.”

“One of the things I found remarkable was how they described their reactions, how they described how they were feeling in this political environment,” she says. “People would say things like, ‘I felt like I was suckerpunched. I feel as though I’m unsafe everyday. I feel as though I’m safe, but others aren’t. People should be afraid to exist.’ There’s this real sense of anticipatory threat that I hear, that people are sort of hunkered down waiting for the worst possible scenario. And the only thing they can do is fight against it. When you’re under threat, it demands a response, whether that’s withdraw entirely and hide or whether it’s come out, fighting.”

Smith says she’s found this response plays a major role in political polarization.

“Under specific conditions of threat… polarization increases,” she says. “As soon as you give people a sort of big problem that they have to solve, the Republicans all try to solve it using Republican solutions and Democrats try to use Democrat solutions, and it makes it really difficult to reach a compromise.”

So what can we do?

Politicians are giving people fewer moderate options. People are stuck in their political echo chambers. And there aren’t many opportunities for respectful dialogue. How can we move forward?

Paine Caufield says people should look for common ground first before delving into controversial topics.

“I believe 100 percent that most Americans…would very firmly agree that this is a country that prioritizes freedom and that prioritizes equality and prioritizes opportunities,” she says. “Those are core to our national identity ….We define them differently. When you start with common values and try to understand how one person can read the value of equality to require affirmative action and another person can read equality to oppose affirmative action, it doesn’t mean that you fundamentally disagree on the importance of equality. It means that you read that concept differently. You can start to then have a conversation about why equality matters, how each of you is going to get there, but start with the foundational core.”

Smith says the environment in which we have these discussions is just as important.

“Just be aware that you’re going to be more likely to have a productive conversation if it’s sort of a one-on-one conversation without a lot of confusing or misdirected factors. If you’re able to really concentrate on the other person’s attitude…you’re going to be able to form a better opinion.”

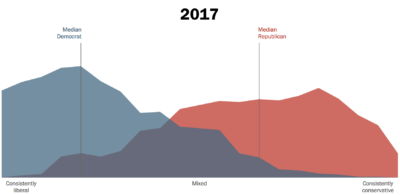

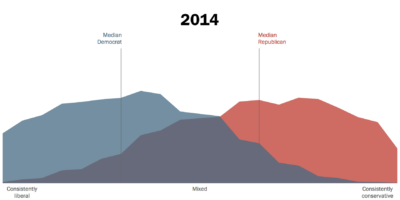

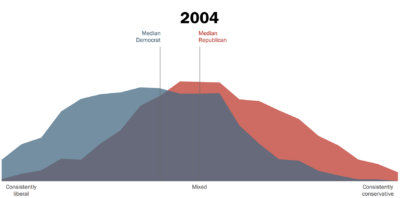

Polarization Over Time

Political polarization seems like the norm today, but that hasn’t always been the case.

“I kind of feel bad for people who have only voted in one election cycle and think a lot of this is normal,” professor of political science Rachel Paine Caufield says.

The Pew Research Center compiled data to show that people hold more partisan views than they did even a decade ago.

Another study mapped the polarization of the House of Representatives from 1949-2011, showing how the members of Congress have become more partisan and less likely to compromise.